Ron Carter photographed by Henry Adebonojo.

Ever the gentleman, legendary jazz bassist Ron Carter welcomes me into his Upper West Side digs with Chimes ginger chews, nimbly unwrapping for me the famously hard-to-open sticky candy with ease, grace, and characteristic courtliness. When I mention how much I love ginger, he grins and shares, almost conspiratorially, where to get the best ginger sweets in New York City–a little Japanese spot downtown.

Apologizing for what will be intermittent noise – the sounds of kitchen renovation – he sits in a Barcelona chair to chat, exuding relaxed elegance in a French cuff shirt and braces; no tie, collar unbuttoned. As photographer Henry Adebonojo snaps off some shots, Sir Ron (he is, after all, Commandeur des Ordre des Artes et Lettres, the highest cultural honor in France) is at turns genial, wry, and reflective.

Only because his accomplishments are well-documented would one know that this trim, vital man is rounding out his eighth decade on the planet. “I have a few years on my calendar,” he chuckles. Non-drinking and only occasionally pipe-smoking, he, as his schedule allows works out with a trainer three mornings a week. It shows. Equally well-cared for is the instrument he’s played since 1959; a Juzek bass crafted in Prague in 1910.

Ron through the years. Left photo, Eastman days. Center photo in July 1973 at Lotos Club, NYC by Steve Salmieri. Right photo by Henry Adebonojo.

In February 1937, Ferndale, Michigan saw the opening of the “fancy” Radio City Theater, a boost during the Great Depression that would provide cinematic entertainment to the community for the next forty years. On May 4, in the rural “black” part of town, the fifth of Lutheran and Willie Carter’s eight children was born. His birth heralded a talent who would share his musical gifts for more than fifty years through performance, recording and teaching; an artist who would immeasurably impact the jazz canon.

Ronald Levin Carter recalls the dusty roads of his proud neighborhood where James Weldon Johnson’s “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” was the anthem of note. “The Star Spangled Banner” was just “some ballgame tune on the radio.” The course of his life was set in 1947 when his mother learned that the local Grant School received an array of musical instruments. She told her children to each pick one. Ron grabbed a cello and his sister Sandy a bass (they would for a time play cello/bass duos around town.) The reserved Ron realized that with his aluminum cello, he could make an aggressive sound, offering him a “voice” that countered his innate shyness. Even though all the Carter siblings played a musical instrument, Ron alone took it to “this extreme that I am going through,” he laughs.

He acknowledges that he has a God-given talent, but honing his craft, mastering his instrument has been the result of years of dedication and concerted effort. He rejects the notion of genetic musicality frequently heaped upon artists of African descent; he finds it reductive. If he’s reached the pinnacle, it’s not because of some magical negro gene, but the fruition of his labors.

The “Carter kids” had usual chores and responsibilities around the house, but Ron began generating income early on with a 300-customer newspaper route while in junior high school. He took his commitment to the work very seriously; when Michigan winters prevented his standard bicycle delivery, he took to the snow by sled. He was able to pay for his own lessons and buy charts, critical in a large family with limited financial resources. Even so, his parents encouraged his pursuit of musical excellence. When not sequestered in solo practice, he performed with his siblings in a family string quartet for his delighted father. While other children listened to popular tunes of the day, Ron was listening to the Bach Cello Suites. By ninth grade, he earned first chair cello at Lincoln High School. Tall and fit, he did a toe-dip in sports but realized that neither basketball nor baseball was “emotionally active enough” for him. Whereas playing music required a concurrent trinity of physical, technical and emotional activity.

Lutheran Carter was, according to Ron, “a great mathematician” limited by era and circumstance, but his integrity was unparalleled and his work ethic strong. With ten mouths to feed, he accepted a job as a Detroit bus driver; packing up Willie and the kids for the Motor City. He built the family home himself, grew some of their food and took on three jobs if need be to keep his family afloat. As he was able, he helped neighbors as well. He was committed to family and community. “We had a spare lot next door,” Ron remembers, “and wintertime in Detroit was brutal; each year my father would put a skating pond out there for the neighborhood.” By his example, Lutheran’s principled and discerning youngest son grew into honorable manhood. Never falling prey to the rapscallion antics of some of his peers, he has built a reputation for responsibility and accountability for his actions– he’s a solid, upstanding cat.

Ron entered Cass Technical High School, the highly-regarded Detroit public prep school in 1952. “You had to audition to get in, pass an exam and maintain a certain grade level to stay there,” he says of his alma mater. “It was like a junior college. Music students had to be in everything: I played alto clarinet in the band; tenor saxophone in the marching band; sang in the choir, man, it was a complete music program.” (He also played the violin, trombone, and tuba.) When he first attended the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, he was blown away by the magnitude of the space as well French guest cellist Pierre Fournier’s performance of Dvořák “Cello Concerto in B Minor.” Ambitious and driven, the budding classical cellist gave up the time-demanding paper route for odd jobs like Simonizing cars on weekends to continue to fund his music needs. He got the occasional gig performing at socials but realized those jobs came far more frequently for his white counterparts. Theoretically, in the protective bubble of Cass Tech, musical proficiency knew no color; one could excel on merit. But beyond its gates, Detroit’s racial polarity reared its bigoted head, infiltrating the bastion of musical equality and disclosing the inequity to the determined young musician.

When bassist Paul Chambers left Cass early to launch a career in New York City in 1955, Ron saw an opportunity. As the only bassist, he couldn’t be passed over because of race “Paul left open a bass chair, so I filled it.” The learning curve was steeper than he’d expected but with typical drive, he immersed himself in learning his new instrument. And he soon discovered a new revenue stream, one which would require the Bach-fiend to play jazz. “In those days, all the frat houses had jazz bands play on the weekends,” he recalls. The high school senior learned a new music library and a different approach to playing, using work as an extension of his schooling. He came to understand the vast gulf between several orchestral bassists playing in unison and the singular heft required of the bass player in jazz, as well as the speed differential of both genres. He explains in his biography Finding the Right Notes, by Dan Ouellette, “I’d been practicing classical my whole life, so I understood scales. I studied harmony and theory at Cass, so I wasn’t a stranger to how a jazz band played harmonically. I played Bach chorales for orchestra, but we played those in half the speed as a jazz tune. I had to acquire a language for playing faster tempos with jazz. The bass lines themselves weren’t complicated but because they came faster than I was used to. I couldn’t think quickly enough to play the right notes that would work.”

On-the-job jazz training aside, he still dreamed of an orchestral career and successfully auditioned for the prestigious Eastman School of Music in Rochester, NY where he received a four-year scholarship for classical bass. In March 1958, he met Syracuse University student Janet Hasbrouck. On June 7, 1958, they married. Retrospectively he jokes that it was “the atomic age.” That Fall, the school established The Eastman Philharmonia with Ron garnering first chair double bass. Life was looking sweet.

The scholarship was a boon, but it didn’t cover everything– “you gotta buy clothes; you gotta buy strings; you gotta eat.” Gigging around at jazz spots like the Pythodd or Ridgecrest Inn helped him remain “financially solvent.” He worked with a local trio as the backup band for touring artists like Sonny Stitt or opening for big acts like Horace Silver Quintet, Dizzy Gillespie’s band, Carmen McRae and Oscar Peterson.” Once again, he delved in, learning by immersion. “They assured me that New York welcomes guys who can play,” especially a good bass player, said Sonny Stitt–advice Ron would rely on when racism once again threatened to dash his dreams.

Graduation day at Eastman with his Dad, Lutheran by his side. Newlyweds Ron and Janet dine at home in Rochester. Photos courtesy Sandy Nixon/Finding the Right Notes

As a member of the Eastman-Rochester Philharmonic, dressed proudly in “vest and tails,” he garnered accolades from guest conductor, Leopold Stokowski of the Houston Symphony Orchestra. Stokowski, however, told him in hushed tones that the board of directors simply was not “ready for a colored man to be in their orchestra.” As Ron retells the story, a hint of the sting is there, a glimpse of that crestfallen young man, long before he carved an exemplary, multi-decade career. One that places him solidly in the pantheon of jazz masters.

With quiet resolve, like his father before him, he adjusted to circumstance and moved ahead–to New York City. The year, 1959, a seminal year in jazz. Drummer Chico Hamilton saw the potential in Ron’s playing; liked his cool vibe and good manners, essential on what was to be a lengthy tour, and hired him. Of that first road experience, Ron says, “it was free school for me just by playing every night. It was an education on taking taxes out my pay, per diem, publishing rights, rehearsals, how bass drum works, ins and outs, do’s and don’ts. It was a great time; eight months.”

Ron then enrolled, on scholarship, in the Master’s program at the Manhattan School of Music. “They didn’t have jazz at the time but had a great theory department, and a great orchestra. It was an opportunity for me to maintain my classical skills and learn another view of composition.”

Juggling classes by day and gigging at night, he finished the program in a year. He entered yet another intense period of learning-by-doing with performances, session work, and touring Europe with “Cannonball” Adderley. He learned about navigating the jazz life from every leader he worked with from Chico and Cannonball to Randy Weston and Bobby Timmons. “It was a good time for me to keep my mouth shut and my ears open,” Ron recalls. He gives props to Bill Lee for paving the way for him to work in yet another genre, folk. “Bill Lee is great bass player and a fabulous writer.” As “King” of folk bassists, Lee was in such high demand, he couldn’t take on all the offers, so Ron took up the slack while learning things he might not have through jazz. With Ron, every opportunity is a teachable moment, whether to him or through him.

Probably the single most influential musician on his approach to playing is not another bassist, but rather the trombonist JJ Johnson, whom he observed over the course of a week-long club date. JJ seldom moved the slide beyond the bell of his horn yet had full command of the notes. It was a revelation. Ron realized that he too could play economically; playing the same notes horizontally that he can play vertically. Maximum results with minimum physical effort.

He completed his master’s studies and recorded his first album as a leader, 1961′s Where? for Prestige Records with his former Hamilton bandmate Eric Dolphy. The following April, as he kicked it with his friend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar on a Harlem basketball court, he got word that it was “time.” Janet gave birth to their first child, Ron Jr. (R.J.) The new papa kept a buzzing work schedule.

In March 1963, just shy of RJ’s first birthday, Ron accepted a gig with Art Farmer’s new band. After a set at the Half Note, Miles Davis, looking to reboot his disbanded quintet, approached Ron to become its first member. Honoring his previous commitment, Ron respectfully declined. If Miles wanted him, he’d first have to secure the blessing of Art Farmer, who by-the-way, gave it graciously.

Though there were audible groans from early audiences when he took the bandstand with Miles, Ron once again ably filled space vacated by Paul Chambers. After some West Coast dates and personnel changes, Miles had Ron, Herbie Hancock and 17-year-old drummer Tony Williams meet at his 77th Street home. In his rec room, Miles played a few notes and excused himself, leaving the musicians to chop it up on their own as he, unbeknownst to them listened in via intercom. A few days like this later, a smoking rhythm section emerged. With the addition of Wayne Shorter on sax in 1964, the celebrated second great Miles Davis Quintet was born with Ron as Miles would say, as “anchor.”

Anchor. Meant as the penultimate compliment by Miles and the countless others who bandy it about in reference to Ron's contribution to the seminal 60's quintet, the word ruffles the bassist's semantic feathers.

“You ever see an anchor? It’s down at the bottom, rusty. No one knows it’s there; no one gives a shit that it’s there, holding the boat back. Anchor of the band? That means the band’s not going anywhere. That’s not what I do, man. My job is to knock your socks off. An anchor is dead weight; it’s corroded. If you want to think of me as an item, think of me as a nice guy who wears great ties and plays bass, I can live with that,” he laughs. A more apt analog, he contends is, “the bassist is the quarterback in any group, and he must find a sound that he is willing to be responsible for.”

Ron’s responsibilities within the group expanded beyond sound. Known for his honesty and reliability, he became the straw boss, managing payments to the band. But by 1968, Miles was going electric, baby Myles had joined the family, and Ron was neither interested in plugging in nor spending time away from his children. An era was over.

That’s not to say that he never picked up the electric bass. Monk Montgomery first recorded on the Fender in the early fifties with Lionel Hampton’s band. By the next decade many New York session double bassists--Steve Swallow, George Duvivier, and Ron included--were picking them up as well. They would carry both electric and acoustic instruments to sessions; prepared for whichever direction a producer might take. It’s Ron’s basslines that intro the funky paean to New York’s most populous borough, Roy Ayers Ubiquity’s oft-sampled “We Live in Brooklyn Baby.” But ultimately he made a “conscious choice” not to double-dip. He was committed to family and as is his wont, playing a new instrument, would require going all in. He simply didn’t have time for another steep learning curve. He was content to master the acoustic and ultimately gave the electric to his son RJ, who by-the-way, now plays electric bass professionally.

The incredible output of those five years with the Davis quintet is certainly a career highlight, but only one of many. In the nearly fifty intervening years since he’s become the most recorded double bassist in history. With greater than 2,000 recordings to his credit, he has recorded either as a leader or a sideman at least once each year hence. Unsurprisingly, the prolific session player has graced a robust number of impressive releases from his comrades in jazz. His contributions, however, cross genre boundaries from overdubs for Jefferson Airplane to laying it down on Tribe Called Quest’s “Verses from the Abstract.” Aretha Franklin. Phoebe Snow. B.B. King. Bette Midler. Billy Idol. Erykah Badu. Grace Slick. Jessye Norman. Paul Simon. They are but a few. For the Red Hot series fighting AIDS through pop culture, he partnered with MC Solaar on “Un Ange en Danger,” in 1994 for Stolen Moments: Red Hot + Cool. In 2014, he partnered with Gary Bartz on “Cello Suite No. 1 for Red Hot + Bach"

A tiny smattering of his many recordings with other artists.

As a leader, he's recorded more than thirty albums including returns to his classical roots with Ron Carter Plays Bach and Brandenburg Concerto. His Ron Carter Nonet marries bass and cello in a strings-heavy configuration of Ron on the half-sized piccolo bass, a double bassist, piano, drums, percussion and a four-piece cello section. Their biannual Birdland gigs aren't to be missed. The Ron Carter Quartet just wrapped a stellar week-long engagement at the Blue Note. The Golden Striker Trio is a tight trinity with Russell Malone on guitar and Donald Vega ablt taking on piano following the passing of the brilliant Mulgrew Miller. Last year Ron released Ron Carter: In Memory of Jim in tribute to late guitarist Jim Hall, with whom he has performed and recorded as a duo since the 1970's.

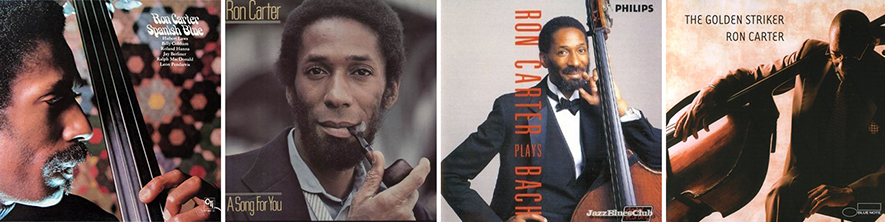

A small cross section of his recordings as a leader.

Having played with nearly everyone in the genre, he has endured the loss of his fellows many times over: Dolphy, Miles, Tony Williams, Sir Roland Hanna, Horace Silver to name a few. In 2013 alone Mulgrew Miller, Cedar Walton and Jim Hall passed away. As is his way, Ron moved through wrenching loss with music. On the day his beloved father died in 1988, he was to open a week-long engagement at Fat Tuesday’s in NYC. He honored the commitment and played “Just a Closer Walk With Thee” in his father’s memory. His family delayed the funeral in Los Angeles until Ron could be there. On April 25, 2000, one day after Myles’ twins were born, Janet Carter passed away. Ron celebrated her life with a memorial service on Saturday; a private funeral with their sons on Sunday; and went into the studio to record his next album, When Skies Are Grey on Monday morning in tribute to her.

Among Ron’s countless contributions to the music is the piccolo bass in the early 1970s. In an effort to bring the double bass forward both physically and sonically, he incorporated higher tuning; ostensibly a cello tuning inverted to blend the potentials of cello and bass. (Stanley Clarke is credited with pioneering piccolo tuning in the electric bass during the same period.)

During the heyday of advertising jingles, Ron embraced the form. Sure, the money was good and the hours short, but it presented an interesting challenge, creating music to fit a 30-second spot. That he was punctual, quick and well-versed in a variety of genres kept him in heavy rotation. Always expanding the boundaries of what can be done with the music, he began to compose for film and television. To score Bertrand Tavernier’s medieval tale Beatrice, he researched the music performed at court and the instruments of the era: sackbut, viol, medieval trombone, and hurdy-gurdy. In the group, Concert Dans L’œuf, he found musicians proficient in these era-appropriate instruments. In 1988, he won his first Grammy for his composition, “Call Sheet Blues,” from the Tavernier film ‘Round Midnight. As end credits roll, Ron, Christian McBride, and Don Byron close out Robert Altman’s Kansas City.

Impeccable at the DC Jazz Festival. Photo: Sharon Pendana

With an unwavering commitment to students, he has served on the faculties of the Manhattan School of Music, the Music Department of City College of New York (now Distinguished Professor Emeritus) and Juilliard Jazz. Managing his touring schedule around his teaching schedule, he would fly back from a gig anywhere in the world to arrive on time for class. He still gives private lessons in his home to a select few. Recipient of an honorary doctorate (one of a few) from Berklee College of Music in 2005, he gave the commencement speech and quipped “I am a retired schoolteacher, working on weekends.”

On a stellar Wednesday night in June 2007, he took the stage at Carnegie Hall dressed in an Issey Miyake tuxedo for a four ensemble performance in celebration of his 70th birthday. The set opened with his fellow Davis quintet alums, Herbie Hancock and Wayne Shorter with drummer Billy Cobham. Sans brass, he moved on through his duo with Jim Hall; his Golden Striker Trio; and rounded out the evening with the “Dear Miles” quartet (Stephen Scott, piano; Payton Crossley, drums; and Rolando Morales-Matos, percussion.) With these groups, he’s demonstrated the viability of the bass as the lead, coming “out from behind the palm tree” with such dexterity and presence that the horn is never missed. His drummerless trio subverts the traditional conception of the jazz trio as piano, double bass, and drums. His is a mission to continually expand the canon and the breadth of his instrument’s role in it.

He continues to work with his various ensembles, touring domestically into the Spring. He’ll take the trio to Zurich in May. He will on occasion, perform with other respected leaders. In late January, he and drummer Lenny White kicked the rhythms with the Wallace Roney Quintet. By the time he took his hauntingly beautiful solo, “You Are My Sunshine” in the late set, he appeared as crisply elegant in pinstripes as if he’d just gotten dressed. He clearly has gotten the maximum performance/minimal exertion thing down. He’s had trainers and orthopedic doctors observe his movements in performance and even in transporting his instrument to understand the requirements of the body in what it is he does so that they can suitably advise him.

The late hours of a jazz musician caught up to him one Sunday in the early aughts during a church service. The lovely Quintell Williams, who typically sat in the balcony, took a seat in the main nave. Much to her dismay, the sermon was punctuated by the snoring of a sleeping man seated next to her in the tiny pew. With a gentle elbow nudge, she asked, “So where were you last night that you can’t stay awake in church?” Humbled, Ron apologized profusely, explaining that he was a musician, and that he had performed the night before. After the service, he invited her to hear him play at Iridium. Which she did. Taken by the warmth of the hug he gave her in thanks, she consented to see him again. They soon discovered they were both Detroiters from large families with similar values, had attended Cass Tech, liked vintage cars, great clothes (she’s a terrific tailor and seamstress) and each other. The widower and the former model married on July 25, 2012. Mrs. Carter says of her husband, “He’s very funny, extremely kind and he’s sensitive. If he comes across as stern, that’s only because of how he feels about the music.” His is a lifelong quest to find those right notes.

The Commandeur des Arts et des Lettres medal; Ron with his twin grandsons, Ronnie and Myles; Ron and Quintell in selfie mode; one of Ron’s Grammy Awards: his handsome sons, Myles and Ron Jr.; his youngest grandson, Seen and his eldest grandson, Nelson.

He feels very strongly about the need for arts education and access. Just as he was introduced very early on to the wonders of musical possibility, he strives to do the same for succeeding generations of children. Launching the Finding the Right Notes Foundation last May, he enlisted the expertise of artist, writer, and arts administrator Danny Simmons. “People are transformed by the arts. That’s why I’ve joined with Ron on this. It’s so important that he’s [Ron] leveraging his notoriety to make a difference for people who might not have that opportunity if not for what he’s doing,” Simmons said at the launch. Singer/songwriter Renee Neufville is aboard as a brand ambassador, and the immediate goal is to enlist more artists and performers to join them as they advocate for arts engagement in the schools.

Ron recalls the New York Philharmonic’s annual concerts at Abyssinian Baptist Church. “My image of it is there are four buses outside with the motor still running. Folks inside play the concert and before the last note drops, they pack up, get on the buses and come back home.” In his estimation, it should have been much more interactive. “Have the concerts early enough in the day. Let the kids get in there, walk around the orchestra. Let them see what goes on. Let them put their hands on a violin and see what that does,” he says emphatically. “I’m trying to fix that with this foundation.”

He is certain that parental engagement and commitment will be crucial to the success of their programming. “Once a child expresses interest in the arts we hope to be able to nurture it,” he says. “But my hope is that the parents will be enthusiastic about their children showing interest in music such that they are willing to practice for an hour every day in lieu of what they would normally do with that time.”

Though the Detroit-based Sphinx Organization, which advocates for diversity in the arts, has since its 1990’s inception seen the numbers of Black and Latino orchestra members double, the numbers are still woefully small. Today they comprise a little more than 4% as opposed to the earlier 1.5% of all orchestras in the country. Just a drop. These numbers raise Ron’s ire. “Start in 1950, look at the orchestra. Then look at ten year periods; look at the number of black faces. I get indignant when I look at these schools turning out these string players for a job that doesn’t exist for them.” He considers his personal experience. “The slights. We like to think we’ve gotten inured to them, that they aren’t so tough anymore.” Hardly. Along with his mighty musical legacy, he hopes to leave a world more just than the one he has inhabited. As a man of integrity, of course, Dr. King’s “content of their character” resonates with him. As an artist, he might add judged not by the color of their skin but by the commitment to their craft.

Finally, the TROVE of the most recorded bassist in jazz history/bandleader/composer/arranger/educator/author/family man, Mr. Ronald Levin Carter…

1. The scent of lavender.

2. Aural glow from his instrument. That transcendent moment “when the sound of my acoustic bass seems to glow in the dark,” is a particular favorite.

3. Making my wife smile. Quintell says that being with her husband is “a slice of Heaven.”

4. Hearing the sound of a Formula One car engine shifting through the gears. It’s a sonic delight that the fast car enthusiast can enjoy through the marvel of his Tetra Speakers.

5. Knowing that I helped a fellow musician play better/differently. Jazz bassist and professor at Rutgers, Kenny Davis, shared that many years ago as a private student of Ron’s, the maestro once positioned his fingers for him and left the room as he continued to play. Ron called out to him when he “heard” Davis’ lapse from the corrected form, changing the intonation. He gives Ron high praise for making him a better musician as well as teacher. "Studying with Ron is like studying with Michael Jordan or Dr. J for basketball. He's a master; like studying piano with Mozart. I'll still call Ron to this day if I have a question. I respect him not only as a bass player, but as a man, and for how he conducts his business," he says.

6. A great home-cooked meal. Pretty easy to come by when your son is a chef and your wife can “burn” too.

7. Flying home on American Airlines. After touring its always great to get home with an airline he can rely on.

8. Morning Light Service. The intimate, early-morning gathering for meditation, scripture, homily, discussion and Holy Communion each Sunday at Riverside Church is “very centering. It’s a perfect start to the week,” he says.

9. Wearing a great tailored suit/shirt/tie/combo. F-One in Tokyo, for whom he appears in advertising, makes most of his suits, though he has been known to occasionally don one created by his wife. He gets his custom shirts from Paul Stuart in New York. For finishing touches, he loves Ferragamo ties and Hermes pocket squares.

10. A hug from a friend. And he gives as good as he gets.