Leonardo Benzant photographed by Henry Adebonojo for THE TROVE.

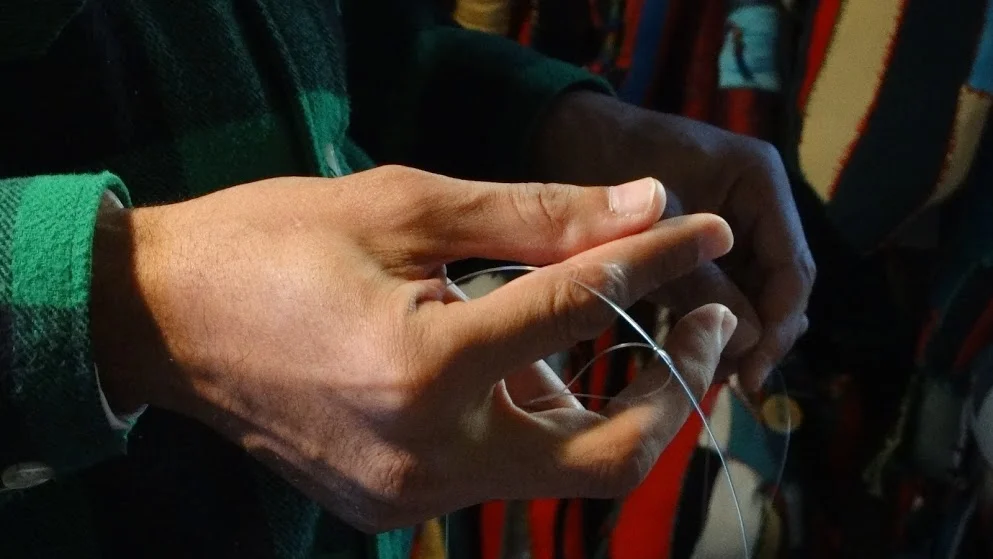

Moving rhythmically, his hands, at first glance unblemished by long-ago surgery and skin grafting, string tiny Czech glass beads into lengthy strands of variegated color, each taking days to complete. “Sometimes I cramp up a little bit if I am working too much, but it doesn’t impede anything. It just forces me to use my hands differently,” says artist Leonardo Benzant. The strands, he explains, are then wrapped around hand-stitched appendages crafted from bundled fabric, bits of soil and plant life, rum, bone or even saliva. “There’s a prayer inside each of the forms and if not a prayer, coins or other things that are symbolic.” The striking assemblages, as well as his ideographic paintings, have garnered considerable notice for the self-described "urban shaman" with acquisitions by the Harvey B. Gantt Center and major collector Peggy Cooper Cafritz as well as multiple shows in Brooklyn, Charlotte, Detroit, and Philadelphia last year alone. Curator Dexter Wimberly presented his work in March at Volta NY, the invitational art fair on Manhattan's Pier 90 and at the current exhibition, Afrosupernatural, Benzant’s first major solo exhibition. At Newark’s Aljira, a Center for Contemporary Art through April 30, 2016, it is the culmination of years of exploration into the spiritual legacies of those who survived the torturous middle passage of the Transatlantic slave trade. The work delves into our collective unconscious and reveals our “African retentions.” It encodes and re-members African cultural memory from the Motherland throughout diasporic dispersal, offering it as a healing steeped in his knowledge of African cosmology and funneled through the precepts of Hermetic Philosophy. Natural and supernatural concepts converge in a potent cauldron of spiritual syncretism, a fusion of earthly and ethereal realms.

Stringing beads. Photo by Sharon Pendana.

I first encountered Benzant's work at Rush Arts Gallery in New York. Drawn as I am to traditional beadwork of indigenous cultures, I fancied his contemporary usage of beading in pieces from his ongoing series Paraphernalia of the Urban Shaman M:5 (cleverly abbreviated as POTUS M:5). Encased in beaded bands of color evoking chromosomal patterning, the tubular suspensions, inspired by African power-objects, are imbued with the spirit of Bakongo antiquity; merging notions of the physical at the cellular level and the metaphysical. We sat down to talk as he supervised the installation of new "POTUS" works at yet another Rush-sponsored exhibition, Power, Protest and Resistance at Brooklyn's Skylight Gallery. He spoke movingly of his upbringing, his identity as a man of Afro-Dominican-Haitian heritage and how his spiritual practice of the Kongo-derived, Afro-Cuban tradition Palo Mayombe informs his artistic practice. We met soon after as he finalized the works for his solo exhibition Cosmology of Resistance and Transformation at the N'Namdi Center for Contemporary Art in Detroit and once again on the eve of the Afrosupernatural opening.

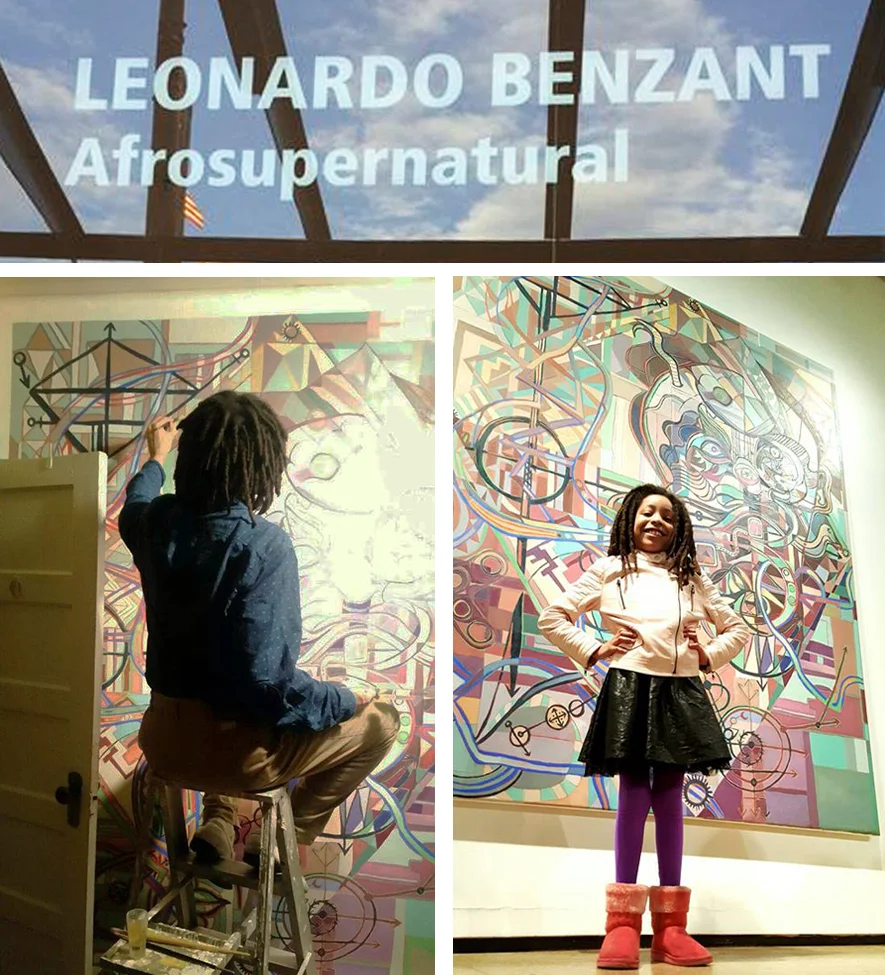

The Afrosupernatural exhibition signage at Aljira; Leonardo at work on Subterrestrial Magik; Maia Estelle Benzant-Pérez proudly stands before her father’s finished work at the opening. Photos courtesy of Leonardo Benzant.

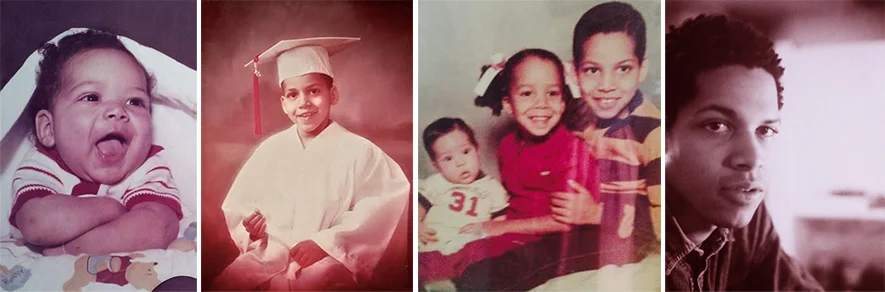

Born in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, the first of three children to Dominican immigrants Leonardo and Fior Daliza Pérez, Leonardo Benzant the artist pays homage to his Haitian ancestry with his maternal grandfather's surname. "A heritage that so many Dominicans have as well, but to assimilate they deny, or negate," he asserts. The Pérez children, Leonardo, Fiorhina, and Hamlet, grew up in pre-gentrified Bushwick, Brooklyn, "back when it was wild," he says. A non-traditional learner transported by his daydreams, little Lenny’s ethereal drifting got him in trouble in class, and in peril on the block. Once, while sitting on his stoop, staring off into the sky, his reverie was shattered with an unprovoked sucker punch to his ten or eleven-year-old face. When asked about the irony of his former neighborhood’s emergence as a magnet community for artists, he replies, "I'm not pulled to go there." His time there was both fraught with challenge and wrought with beauty. "Bushwick was rough, but it was also magical, poetic." His voice trails off; he is visibly moved. He speaks in long pauses, reflective, twisting his locks as if to access his thoughts. “I could just look out the window and see the world; my block was the world. I could see the kids playing in the Johnny-pump and walking their dogs, people coming and going to work, but I could also see the people lined up to get crack.” Though it was often a violent environment, “it didn't stop me from going to the park to play on the see-saw or go on the swings even if there was a junkie on the bench shooting up."

Lenny from the block: at 2 months, in Kindergarten, with little sister Fiorhina and baby brother, Hamlet, and as a teen. Photos courtesy of the Pérez family.

When I visited his studio in his family's Queens home, eight-year-old Maia, Leonardo's daughter with wife Lisa busied herself with schoolwork. A warm, bright child, Maia shares the creative spark of her parents. "She is fascinated with performers and performance. She loves music and movement," her father says. "We’ll play with body paint at home, play music and dance.” She and Lisa appeared with him in a 2013 performance collaboration, The Trinity. “She’s always watching me as I’m stringing beads or sewing or assembling something or painting or mixing colors."

Leonardo's beautiful wife, jewelry designer, Lisa Shears and their daughter Maia. Photos courtesy of Leonardo Benzant.

Leonardo expounded on what had choked him up as he reflected on his early life. “Memories are very vivid for me. They are intensely laced with emotions. Some say I have a photographic memory. Certain things about older men resonate with me. Sentimental things. Some of those men have the migrant experience. They still have the nostalgia; they listen to the old boleros. It’s a romanticism about who you are; where you come from; the food you eat; the smells, the sounds, the percussion that the old men would play; the slamming down of the dominoes; junkies nodding. There’s strength in that world because people survive in spite of how hard things can be. I parallel that to our experiences as people of African descent. It’s a story of resilience. People like to focus on the slave narrative or the struggle, but I like to celebrate the things that are beautiful about us in spite of our enslavement and colonialism. We were supposed to be annihilated, and we’re still here. We still have African retentions.” He brings it to the micro level: "I wasn’t supposed to make it. I was told I was gonna be a high school dropout; I was gonna end up going to prison, strung out on drugs, or killed. I lot of people that I knew; that’s the way they went out. But even when I was standing on the street corner hanging out; doing aimless things, there was something always inside of me--like a dream--I felt was possible beyond that world. And my father," he recalls, "always wanted to try to keep me out of the street, so he would bring me to martial arts classes or drive out of his way to take me to collage class at Pratt or whatever.” He did survive. Bullying and the streets and addiction. His brother Hamlet calls him one of the most courageous people he knows and lauds him for being true to himself "even when it's been unpopular." Leonardo says, “the survival aspect of our stories, that’s the magical, poetic thing that I move with.”

Over coffee, he speaks candidly about his battle with and triumph over addiction; his shaman's journey through crisis. He started drinking at eleven or twelve, sipping from the grown folks’ cups at parties. "I always wanted to be like my uncle. He was very stylish;he had what the Dominicans call muela, charm, the gift of gab. I was like hey, my uncle’s cool, and he drinks. Growing up in the "whole b-boy culture, hip-hop culture, people would talk about smoking a blunt, and I was always the younger kid hanging with the older kids. 'Yo shorty, you wanna sniff some of this?' Fourteen, that’s when I got introduced to cocaine." It frightened him because he liked it so much. Seeing Papo, a friend's speedballing uncle shoot up brought a mixture of fascination and revulsion. And created an indelible memory. By his early twenties, Leonardo “had a psychotic break.” On June 15, 1995, “I just bugged out. Hallucinations, hearing things. I felt like I was losing my mind. I was like I can’t do this anymore.” After wandering around that night unsuccessfully trying to maintain some semblance of equipoise, he called 911. “That was the last time that I got high. No alcohol. No cocaine. No marijuana. No more substances.”

“The most significant thing when I got clean was I no longer had this time-consuming habit; this energy-draining monster that just kept me out all sorts of hours chasing something. I think addiction for me had been the fear of being myself; of accepting myself.” Getting clean was a game changer. “I learned how to focus; how to develop discipline. I became a person who would get up and work on my art. There was nothing else I wanted to do."

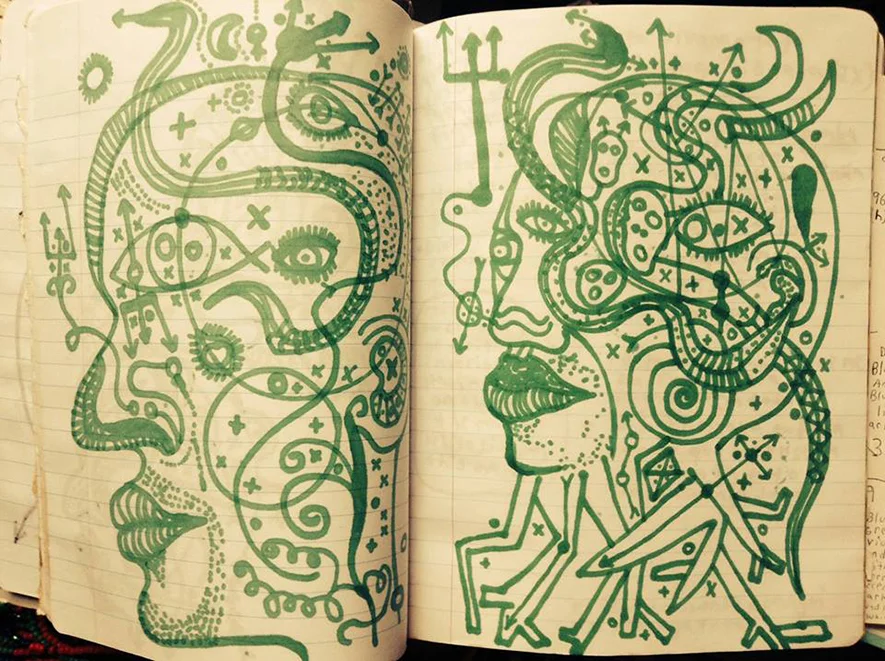

One of many sketchbooks. Photo courtesy of Leonardo Benzant.

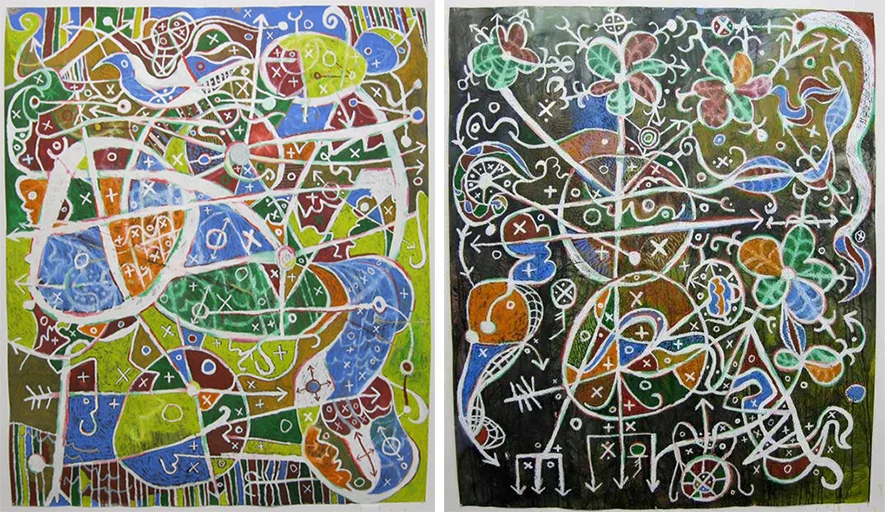

Duality and juxtaposition are recurrent in his work, and the familial influence becomes apparent over the arc of his artistic corpus. “We’re like the latest model of our ancestors,” he says. His paternal grandfather was “the pharmacist for his town in the DR.” His father likes botany; some of the healing plants in the Pérez backyard find their way into Leonardo's work. “My father would draw a diagram any time he tried to explain something to me. And there’s a diagrammatic sensibility about my work, especially in my paintings." The genesis of his sculptural work in textiles and adornments and the performative aspect of his oeuvre are from his maternal line. "My grandmother sews and my mother, she is very into clothes and jewelry. To her, getting dressed is a performance ritual. I like the way she juxtaposes different colors and patterns. It's very African even if she’s not conscious of it. Those patterns represent rhythms; how African music is structured, with polyphony and polyrhythms and time signatures simultaneously interacting in call and response." Mrs. Pérez's aesthetic, a vibrant elegance, permeates the early 20th-century home with blues and golds, brocades, dark woods and crystal chandeliers.

As photographer Henry Adebonojo snapped some shots of Leonardo outside the family home; I spoke with his kind-eyed and welcoming parents in their tastefully appointed bedroom as they showed me a treasury of framed family photos. The Pérezes have known each other since they were eleven-years-old back in their Dominican Republic hometown. Mr. Pérez says they used to play together and that he and his brother fought over her. “I won,” he grins. “We’re going to be fifty soon,” he adds about their impending 50th wedding anniversary.

Early on Mr. Pérez took a correspondence art course with Lenny to help him with his drawing. "He wasn’t even able to talk, and he was already drawing and painting," he says. Because her son was "always daydreaming or drawing" in class, Mrs. Pérez made frequent visits to the Principal's office, "They kept calling me; almost every week! He wouldn’t do his homework," she exclaims. "The school curriculum wasn’t for him," Mr. Pérez chimes in. "He was either painting or fighting or breaking the school law." After transferring him to a Catholic high school, Bishop Loughlin in Fort Greene, they started getting calls of complaint from the priest. Eventually, they got a good call. There was an exhibition of student artists at the school, "and we went to support him," Mrs. Pérez says. "Lenny won the first prize out of 66 paintings! He won a medal and a bonus.” "It was, I think, $500," Mr. Pérez adds.

Leonardo and Fior Daliza Perez on their wedding day and today. Photo by Henry Adebonojo for THE TROVE.

They show me the colorful abstract painting, which now hangs over the stairs. “I always love this one,” the proud mom says. “It was in a gallery in Brooklyn, and when the show was over, Lenny said ‘okay, this one is yours.’" “We are definitely proud of him,” Mr. Pérez says. “In the beginning, I was a little concerned with his career because coming from a poor family, being an artist is not easy. I was thinking about a conventional kind of career: an accountant, a lawyer, something like that. I’m very grateful that I didn’t interfere with his path.”

We join Leonardo and Henry in the kitchen where Mrs. Pérez, a fastidious Virgo adds, “I pray every day for him so he will keep achieving his goal, but you know the part I don’t like is when he has to work. I know the space up there is small, so he takes my living room; he takes the whole house!” Everyone laughs “I’m an invader,” Leonardo says, adding “there’s a relationship between chaos and order in the creative process. Life is messy and fluid; you’re moving and living and things are not static.” Mama

Canto

Leonardo's studio, a sunny yellow sliver of a room, overlooking the backyard garden is brimming with the tools and materials of creation. Nearly every space on the walls and floors is covered by works in progress or objects of inspiration. What little can be seen of the hardwood floors is speckled with the riotous residue of painting, Leonardo's first medium. There are piles of fabric, countless beads, a stack of books precariously balanced on a chair and a Caucasian mannequin head destined to be rendered unrecognizable by his transformation. I ask about a compelling piece on the far wall. Densely textural, richly colorful, it is a crazy quilt given a third dimension; teeming textile masses bound in spirited, free-handed stitch witchery. A piece begun during Maia's infancy, it is Beings Born From Word and Stitch. The shift to fatherhood introduced a different medium to the painter. "I started working with sewing because I couldn’t paint." The new dad switched from toxic oils to acrylic paint to protect the baby, but he realized that painting required full focus. "When you paint, you can’t really deal with anything else; you can’t multitask. Whereas sewing, I could just pick it up, put it down, warm the (bottled mother's) milk." The gestation

Studio vignettes: from a glimpse of one of his favorite quotes on the wall

Though he had never sewn before, "except for maybe my hems," it felt instinctual. “In a lot of African art, there is fiber.” The 2002 exhibit, “The Quilts of Gee's Bend at the Whitney Museum, spoke to me like nothing else. I had been going to MoMA and the Whitney, and it was all Western technique. It was so refreshing to see the Gee's Bend quilts in this institution. It blew my mind," he enthuses. "I could feel the energy and colors. The music. The rhythms. Then I learned that they do it together, that it's communal. They’re part of these prayer groups. It's very African and ritualistic. There’s storytelling

Leonardo in the studio. To the right, Beings Born From Word and Stitch. Photo by Henry Adebonojo for THE TROVE.

He speaks on the synthesis of utility and beauty inherent in the everyday objects of African culture. "Even if it's on an altar and

An art patron moves through Cosmology of Resistance at the Danny Simmons-curated installation at Brooklyn’s Skylight Gallery at Restoration Plaza.

His study of sculpture at Pratt Institute's Fine Arts Center notwithstanding, he considers himself self-taught. "I was creating before Pratt. I figured if I’m gonna make things, I have to do my research, check out museums, go to the library. There was this ebb and flow between spending a lot of time alone and working with mentors, so by the time I got to school, I had a good sense of who I am and what direction I was going." The more intimate nature of mentorship is better suited to him than institutional learning. He recalls the impact of one of his mentors, Magno Laracuente. "He lived in the projects in Washington Heights and the living room was his studio. We’d play music and talk, and I’d watch him paint and draw and mix colors. For years." Laracuente's erudition, extensive library, and meticulous technique influenced him. "Some artists are only interested in what’s happening now; what’s trending, but I am interested in the past, present and future." He circles back to art school."I went to Pratt for practical reasons. Maybe I could get a job teaching, now that I have a daughter. She was the primary motivation.” Fatherhood, he says, "makes you more of a consequential thinker. It forces you to think about the consequences of everything. It makes you think about yourself as a man and how you relate to women. You revise certain things. Should she watch TV or not? What kind of dolls do you want her to play with?"

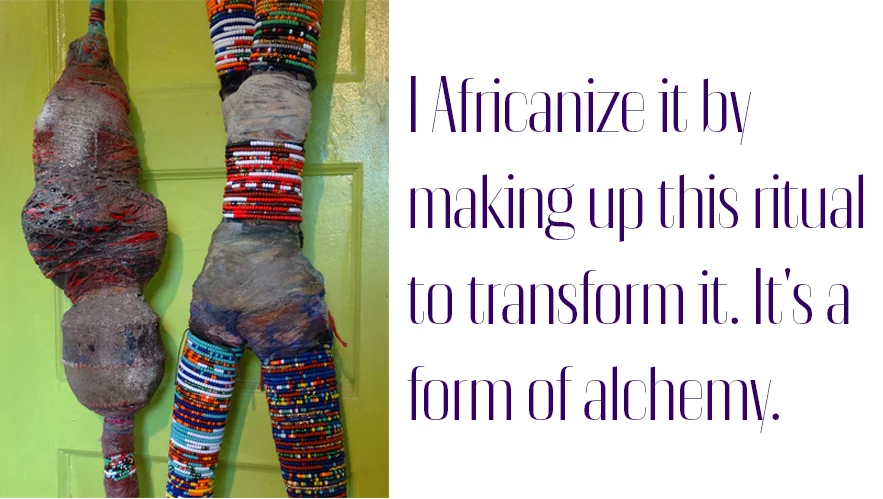

A photograph of his Aunt Connie as a young girl, brown-skinned and clutching a white babydoll disturbs him. "How we’re programmed, the images we surround ourselves with are crucial. My daughter having these dolls would bother me." So he disrupts what disturbs by subverting the Eurocentric imagery. “I Africanize it by making up this ritual to transform it. It's a form of alchemy.” He’ll wrap the doll in fabric and suspend it in head-down inversion--the proper positioning for birth--and layer it with organic materials such as

He’s been examining his connection to his heritage

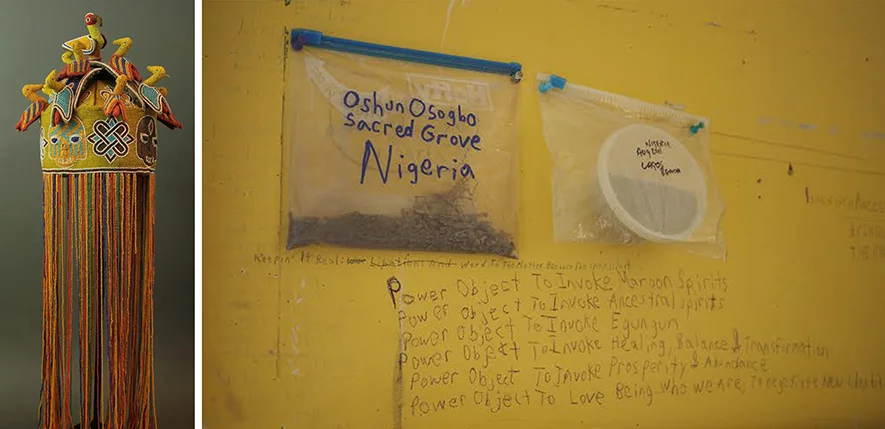

The cultural melange of his Afro-Dominican-Haitian-American heritage finds its way into the work. "I think the many cultural components inform my patchwork way of seeing things. When I think of assemblage, I don’t think of Rauschenberg and modernism, I take it back further, it's very African. Assemblage existed before Rauschenberg’s combines. It just had other names.” Conversely, “people of African descent have throughout history, taken European material culture and transformed it," he says. "Africanized it. That's part of the message for me. These beads come from the Czech Republic, but what I do with them evokes that African or Afro-Caribbean aesthetic." The glass seed beads were "introduced to the Motherland" in the 15th-century. He mentions artist El Anatsui's bottle caps; how they represent rum, which represents triangular trade and how his beadwork is analogous. “Traded for slaves, beads were a form of currency. They are associated with power and royalty. There's a whole history around beads.”

Yoruba inspiration: beaded crown and precious earth from the

He was first drawn to beadwork through the intricately beaded objects enshrined and dedicated to the Yoruba

He explains his process in creating the mixed-media sculptures: “I work with dolls, with fabric, with cardboard tubes. I put holes thru them and make fabric appendages and tubular forms that stick out of them. Once I feel right about the forms, I put the beads on.” But the beading is a long process, sometimes assisted by his wife, mother and daughter. “Months of stringing long strands of beads

His artist’s journey began, however, with the flat image, “drawing, painting, and mark-making.” In Palo ritual, “there are these sacred ground drawings similar to Haitian Vodun

On view at Aljira from the

His continuing series of paintings, Signatures aka AfroSpanglish, is inspired by these Palo power signs. “They serve as a way of directing or manipulating the energy; it's like the signs themselves become a highway; it's like mapping the cosmos; it takes many years to read it and to write." The process is not arbitrary, he contends. “My paintings are pulling from sacred drawings, but it doesn’t stop there. I was thinking how when you salute in a certain way at a ceremony (which he demonstrates) you’re now writing with your body; you’re now signing; it’s codified behavior, body language. There are things that I'm wearing beneath my clothes that are communicating (blue and white ribbons he

In the studio; appendages and a glimpse of Memoria Kongo: Bambula, a magnificent painting for the Afrosupernatural show which incorporates beadwork. Photo by Henry Adebonojo..

After escorting me back to the elevated train, Leonardo strode ahead in his wingtip brogues. With an artist’s talk at

Leonardo treasures most the love of his wonderfully supportive family, who show up for every opening and encourage his creative pursuits; and that of his Mukanda --his Kongo community. But of that which he can enumerate, however, Leonardo enjoys things which have "some sort of spirituality about them that makes me feel connected, in tune with myself, and calm.” Aqui,

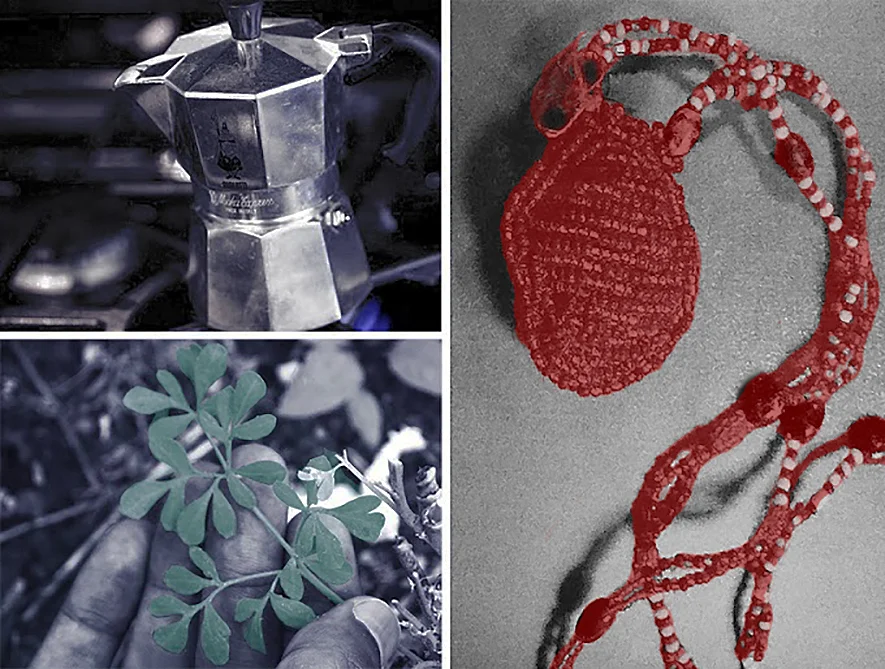

1. Coffee. With a trusty

2. My

3. Preparing a (spiritual)

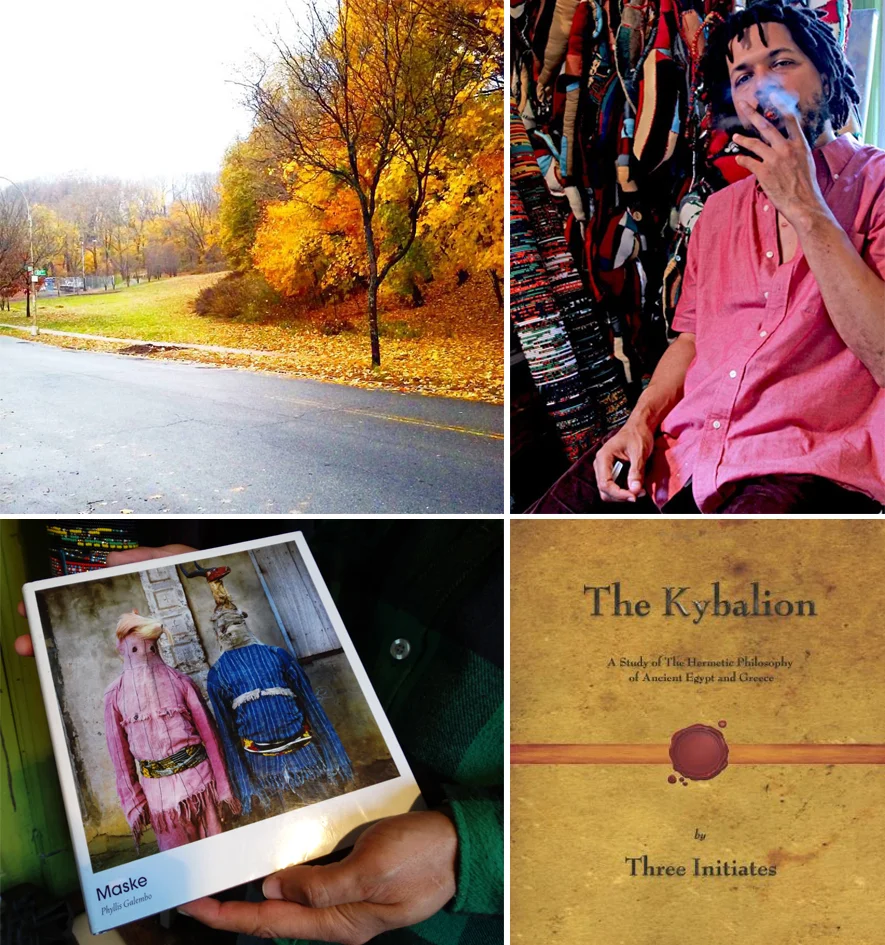

4. The forest. Just blocks from his home, the aptly named Freedom Drive in Forest Park offers arboreal solace from the grind and connection to nature. Photo courtesy of Leonardo Benzant.

5. Cigars. Part of his spiritual practice, they too are

6. The Kybalion by the Three Initiates. Introduced to this treatise on the teachings of Hermes Trismegistus years ago by a Harlem elder named Gene Campbell, he applies the Philosophy of Hermeticism to all aspects of his life. He studied with Mr. Campbell on weekends. "That was a special experience. I’ve always been drawn to those kind of experiences. It’s like small, intimate, I have access to something that’s raw. It’s like a student master situation. He was just brilliant!"

7. Transformation. The verb transform is his favorite word. "To transform or be transformed is an amazing, beautiful experience in life, in art, in spirituality. Everything I see seems to be in a state of transformation, the alchemy of life. I'm fascinated by how one can influence, participate, and generate transformation. The art, the science, and the spirit behind it. And what it all has to do with energy force and vibrations." A book by Phyllis Galembo on Egungun masquerade traditions illustrates the transformative aspect of spiritual and cultural ritual.

8. The beach. With Caribbean heritage, how could he not love the beach? "It does something to me; the presence of the water, but

9. Walking. Whether it’s a stroll along a bustling boulevard, meandering the quiet residential streets or roaming the woods, he is grateful to be ambulant. Photo by Sharon Pendana.

10. Collecting rocks & stones. He gathers them in his travels, sometimes

Find Leonardo on