Victor Ekpuk photographed in the Kingdom of Bahrain before his sculpture, The Face, a tribute to the Bahraini people commissioned by Bank ABC. Photo courtesy of Victor Ekpuk.

From drawings in chalk, destined for erasure to monuments of steel, galvanized to endure, the breadth of Victor Ekpuk's body of work encompasses both ephemerality and posterity; the evocation of memory, elucidating the human condition.

On the first of a couple of studio visits in 2019, the artist had moved through a "season of mournings," the winter passings of peers who shared his artistic and intellectual curiosity. First, artist Michael B. Platt in January, curator Olabisi Silva in February, and both professor Pius Adesanmi and curator Okwui Enwezor during the second week of March.

Bold graphic symbols – vivid red and deep black – push forward from canvases in impasto relief for his planned solo exhibition, Marks & Objects –his first at New York's Aicon Gallery. Yet, for the next in the suite of paintings and a site-specific mural, seemingly apropos, he is contemplating blue. Splashes of the hue, subtle variations of Ultramarine are tacked upon the wall. Referencing artist Yves Klein's registration of the shade as International Klein Blue nearly sixty years ago, he asserts, "They were able to reproduce that blue in a lab that would be stable, but the origin of this is the Tuaregs of Morocco. People used to travel around the world to get it." He adds, "My grotto at Somerset House [for the landmark group show, Get Up, Stand Up Now: Generations of Black Creative Pioneers in London] will be that blue with the writing in white; an Afrofuturist shrine for learning, for knowledge. It will be an alcove where people can come and actually sit and read books, engulfed in my writing."

From Victor Ekpuk | Marks & Objects at Aicon Gallery May 30 – Jun 22, 2019. © Victor Ekpuk; photo © Idaresit Ekpuk

Victor Ekpuk’s powder coated steel sculpture, The Philosopher, 2018, is nestled in a niche of his mixed media installation, Shrine to Wisdom, 2019 from the group exhibition, Get Up, Stand Up Now curated by Zak Ové at Somerset House, London, June 12 - September 15, 2019. © Victor Ekpuk. Photo courtesy of Somerset House.

Gracious in speech, manner and with an easy laugh, he offers a seat and some chai – served in a mug emblazoned with his artwork. Not a reproduction of one his sought-after drawings or paintings, but rather a purpose-drawn composition created on his iPad for his limited-edition collection of wearable art and home goods. He thinks expansively about utilizing new technologies in art, embracing their plasticity. He eschews a purist standard as to what constitutes a viable medium for fine art. He's moved from earthen mark-making in childhood – his first medium, drawing lines in the sand – through the analog tools of graphite, ink, markers, paint, pastels, collage, and prints to digital drawing and computer-aided design. No matter the medium, he says, "The basis of my work is about lines, so I'm still drawing, but I started looking at my drawings as 3-dimensional objects." Apart from the dimensionality of relief painting on canvas, he wanted to impart solid form. And now he can. Using his precise specifications and scanned image files, a fabricator laser cuts the elements to create Ekpuk's work in steel. The assembled sculptures are then powder coated in the brilliant hues he favors for lasting color.

He's excited by the limitless possibility of technology, as in his avocation, photography, where, he says, "the next frontier is software." To those who espouse the belief that the craft of photography has lost its soul to the digital realm, he says, "Well, one could argue that now digital does it so well that the post-work is not necessary. Sometimes I get much better photos with my new iPhone than with the camera. You can't say that one old way is the best way. The end justifies the means."

Long-time muse, son, Idaresit. © Victor Ekpuk

Paraphrasing the title of an impressive monograph of his work, Victor Ekpuk connects lines across space and time, bridging antiquity to the future. His use of tablets from the ancient Qu'ranic prayer board to the 21st-century iPad attests to this vastness. He has participated in biennials in Dakar, Johannesburg, and Havana; and exhibited in Beirut, Dubai, Geneva, Lagos, London, Paris, Provence, Suriname, and throughout the U.S. His work is in the collections of such individuals as Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and institutions, including the Brooks Museum, which commissioned a 58-foot mural, Essence of Memphis, that also appeared on the big screen in a scene with the titular character from the film, Brian Banks. A detail from his painting, Good Morning Sunrise graces Sanctificum, a beautiful volume of poetry by Nigerian writer Chris Abani. We talk from afternoon sun until the blue of that book and of Marrakech's famed Jardin Majorelle, creeps across the sky. As we usher in a new decade, we look back at his life, thriving career, and global reach, particularly this extraordinary past year.

A portrait of the artist as a young Nigerian

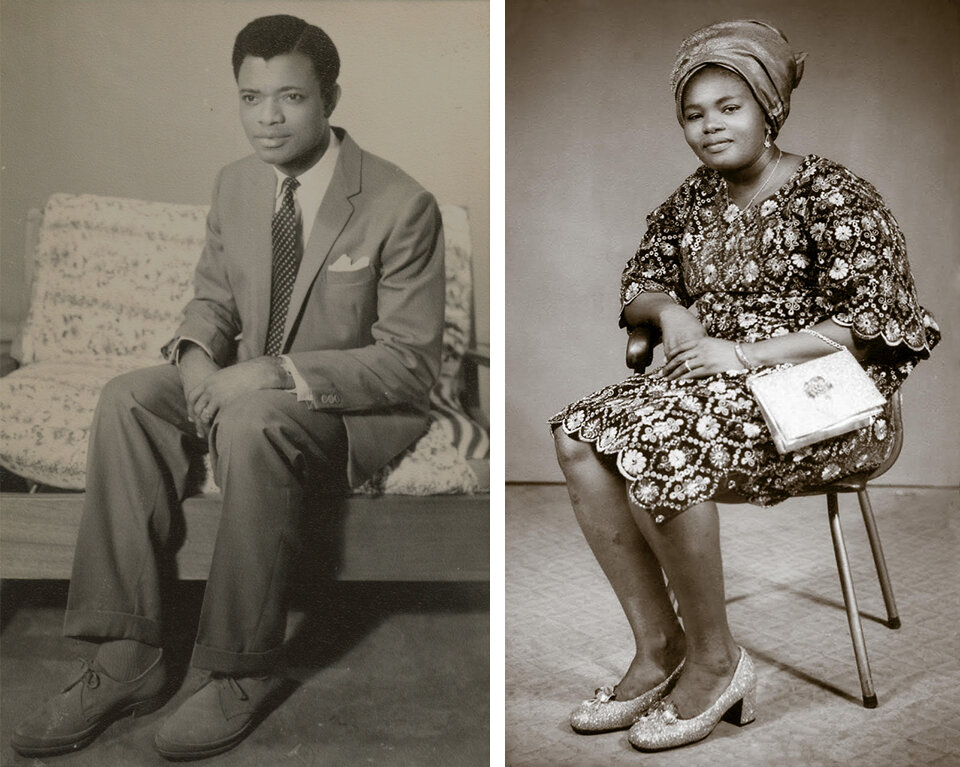

He is the first-born of five children to Sampson and Iquo Ekpuk – a tailor and a seamstress, respectively – in Uyo, Southeastern Nigeria. Since his earliest memory, he's been an artist, demonstrating an aptitude for realistic renderings at merely three or four years old, before he could read or write. He would draw on any available surface, using any accessible tool, even a broomstick in the sand. Spied by invading troops during the Nigerian-Biafran War, his representational ground drawings of warfare raised the ire of the soldiers who warned his parents to cease his output.

Sampson Ekpuk’s sartorial style, circa 1960 with a precision widow’s peak, a dapper side part and sporting suede brogues and a suit of his design. When friends headed off to college in places like Oxford and Princeton, it was Sampson Ekpuk’s tailoring expertise that provided their first-ever suits. His eldest son remembers: ”He would be quite dapper with the hat and matching everything.” The beautiful Iquo Ekpuk created her elegant buba of Swiss lace circa 1970, donning it with dazzling pumps. “I think I got my artist gene from her,” says her firstborn.

He would seek out private spaces to contemplate and create. By second grade, he was making spot-on portraits of family members. "I grew up with these abilities to represent objects around me." Recognizing prodigious talent well beyond that of his playmates, his mother encouraged him. "She put me through a tutelage with a professional artist, a signwriter who lived in my neighborhood to polish me up with composition, and things like that." He entered a countrywide art contest when he was eight years old. "At that young age, I won the competition – my very first. So that's how it all started. Since primary school, everyone has known me as an artist, so it wasn't strange to anyone that I would want to pursue it in college." With a laugh, he adds that though his parents allowed him the pursuit of his interests, they would have been happy if he'd chosen medicine or law. "If you are from Nigerian parents, that's a defacto thing they wish that you do. But it just wasn't me, so there was no pressure."

He remembers his mother, who passed away during his teen years, as "artistic," designing and making her clothing. He appreciates her belief in and support of him. "I think I got my artist gene from her." The loss of his mother splintered his close-knit nuclear family, as different relatives assisted his widowed father with their care. He zig-zagged east and west across the nation's southern region for a few years. First, to the Southwest, to live with an uncle and attend secondary school in Lagos, then he returned to the Southeast for boarding at a prep school and ultimately went west again to the University of Ife. He experienced not culture shock, but adjustment.

"In the Southeast, you have the Ibibios, (from whom he hails) and the Igbos; in the Southwest, you have more Yorubas," he says. "There's a cultural difference and different language groups too." Although he claims that he lacks an ear for language, he was able to learn Yoruba: "If you live in a place for a long time, you pick up the local language. I could actually speak it, but," he laughs, "if someone speaks English to me rather than Yoruba, I will gladly accept it."

He recalls Lagos in the late seventies and the marvel of Festac '77. When the British Museum refused to loan the plundered 16th-century ivory mask of Idia of Benin for the official emblem of the festival, Nigerian artist, Erhabor Emokpae, created a replica in bronze, making the Iyoba's (Queen Mother) likeness arguably the most recognized African mask in the world. "I got exposed to cultures of different places that I didn't even know existed," Ekpuk says. "I watched most of it on T.V. The whole country was celebrating blackness everywhere in the world."

Within days of the February 12 closing ceremony, a barbarous swarm of soldiers, rolling one-thousand deep stormed Fela Kuti's compound, brutalizing all inside, including his respected, septuagenarian mother by pitching her out a window before setting the whole scene ablaze. "Nigerian police and the army were not particularly kind. They threw his mother off of the balcony, and she eventually died," Ekpuk says of the feminist activist Funmilayo “Mama Fela” Kuti. He vividly recalls law enforcement tactics during student rioting at the University of Lagos, which sat adjacent to his high school, St. Finbarr’s College. "I remember when that riot started, and the police started throwing tear gas. It came into our classrooms! I remember that time very well – the dictator that ordered soldiers to shoot students on sight. I had a classmate whose curiosity drove him out - he had a defensive wound on his palm. They [police] wouldn't care if you were a kid or an adult."

Commissions: in the Department of Fine Art studio, University of Ife, creating a portrait of Anglican clergyman, Akinsanya in oil on canvas in 1988; and enlivening an elevator shaft in Hotel Hive, DCs first pod hotel in 2016. © Victor Ekpuk. Photos courtesy of Victor Ekpuk.

Some three hours from Lagos, Ekpuk majored in painting at the University of Ife (now Obafemi Awolowo University), a revelatory experience. "We were encouraged to tap into African aesthetics for expression as artists. Whether you were a fashion designer, a product designer, a painter, we were always taught to look inward." After Nigerian independence in 1960, he says, there was a consciousness shift. "It wasn't just about the British leaving, it was about accepting your Africanness and all the things you'd been told to reject. So the schools, college curriculums started to change, and it reflected cultural values in poetry, writing, and visual arts."

Enter nsibidi

It so happened that he hailed from the region of the country where all-male secret societies practice the ancient form of sacred communication, nsibidi, which transmits coded messages through gesture, spatial placement of objects, and ideographic symbols representing concepts. Though the fullness of meaning is revealed only to initiates, the practice is an open secret in the culture of Southeastern Nigeria, and the uninitiated know to steer clear of spaces marked with nsibidi objects. Ekpuk likens this line of demarcation to yellow caution tape in the West.

"So as a painter, I looked into the traditional culture for my aesthetics, and I gravitated towards the writing systems of Nigeria. Even though I knew about nsibidi growing up and it was always a part of my life, I never really thought of it that way." He laughs. "I guess that's one of the benefits of going to college, opening your mind."

His encounter with the art of painter and poet, Obiora Udechukwu, whose embrace of Uli – an Igbo women's practice of abstract body and mural painting – and the ideograms of nsibidi, sparked a seminal direction for his work. "A light bulb went off in my head," Ekpuk says. "He was also applying nsibidi in his compositions. I grew up with this; seeing nsibidi being performed, because it isn't just writing, it's speech, it's body language, it's communication. You could watch and enjoy the aesthetics of the performance even if you don't know what it means." His exploration of nsibidi shaped his "aesthetic philosophy of reducing forms to their essence" and informs the more recent performative aspects of his ephemeral drawings, treatises on memory. As he is not an initiate in the secret Ekpe (leopard) Society of the Ibibio, his works are not to be read as a literal translation of nsibidi symbols, but abstractions of concepts. He adds that although quite a bit of his work makes social commentary, sometimes he simply enjoys the act of creation: "process and playing with form. It's not always going to have some big political statement to make." What remains consistent is his fluidity of line and singular visual language that expands upon the arcane codes of nsibidi into new vocabularies, a broader spectrum of meaning open to interpretation.

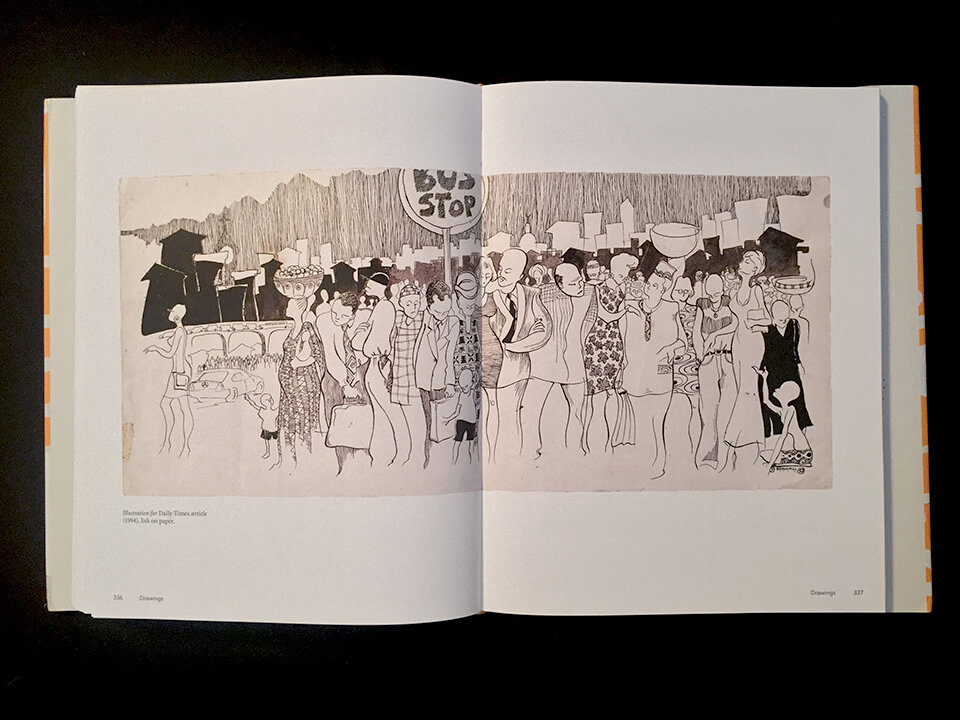

He has, since graduating with a bachelor's in Fine and Applied Arts, been "making art of one form or another," whether fine art or adjacent work as a full-time educational book illustrator for a publishing firm, design consultant for an advertising firm or editorial illustrator for Nigeria's Daily Times newspaper. His post there eventually morphed into that of cartoonist, making caricatures of politicians and other notables. His illustrations helped make the editorials accessible, the gist of the story made clear at a glance. "I also think it brought art into the paper," he says in retrospect. "I did that from 1990-1998, and I would come home and paint in my studio. While the newspaper job gave me visibility and gave me access, it didn't so much pay my rent." He laughs at the irony. "The work I was selling in galleries in Lagos, that was really paying my rent, but if I were to go tell my landlord that I was an artist, he wouldn't have given me his house." Laughing, he says, "he would have said, Where's your address; where do you work?"

From Victor Ekpuk: Connecting Lines Through Space and Time: an illustration for Nigeria’s Daily Times newspaper, 1994. © Victor Ekpuk

Creating family

While working for the newspaper, a mutual friend introduced him to Marion Johnston, an American on assignment in Nigeria for the U.S. Department of State. He borrowed a book from the lovely, multilingual Californian and, upon returning it, their spirited discussion left them curious to see each other more. "We decided we liked each other enough to ask, she said yes, and we got married in Nigeria," he chuckles, condensing the story. At the end of her assignment, he joined her on her return to the United States and the nation's capital, where he maintained an art studio in their home. With full faith in his capabilities, he relentlessly pursued his art. “What’s on the other side is never guaranteed, but we dare our dreams nonetheless,” he says.

Still smiling: Marion and Victor Ekpuk. Photos courtesy of Victor Ekpuk.

Diplomacy and an international art practice make for profusely-stamped passports among the Ekpuks. They lived for a time in the Netherlands and in the Republic of Benin - the land of the Amazon of Dahomey Kingdom. They returned to the U.S. and its medical facilities for the birth of their son, Idaresit ("joyful heart"), in 1999. "Three months later, we took him back to Benin," he says.

Having shown internationally early in his career gave Ekpuk entree to Smithsonian curators already familiar with his work when the young family came back to the States. His first exhibition in a national museum was a group show, Inscribing Meaning: Writing and Graphic Systems in African Art at the National Museum for African Art (NMAfA) in 2006. He's since cultivated a fruitful relationship with the museum, which has archived, he says, "all the newspaper illustrations I could get my hands on," acquired other works, commissioned him to create their first ever African Art Award trophy in 2016, and in 2018, granted him a research fellowship.

Sketches of proposed designs for the the Smithsonian Museum of African Art’s African Art Award trophy. © Victor Ekpuk. Photos courtesy of Victor Ekpuk.

Yinka Shonibare, one of three recipients of NMAfA’s first African Art Awards with Victor Ekpuk, designer of the trophy, right, at the Awards Gala. Photos courtesy of Victor Ekpuk.

Eckington Studio, eclectic music, and ephemeral drawings

By 2009, he found a perfect studio share vacated by artist Jefferson Pinder in Northeast D.C. tucked away in rufous beauty in a converted, 19th-century, pillared brick building once home to the Eckington School. It is here for the past decade he has created his art, sometimes in silence, sometimes with music. "I have pretty eclectic taste. I'll show you what I listen to.” He accesses iTunes. and the strains of Swiss harpist Andreas Vollenweider swell. "Caverna Magica, I like that; it feels like I am listening to this 3-D music, all kinds of stimulation going on at the same time. You're not just listening to music, but having an experience of a place. I made work, one of my first ephemeral pieces, using one of his tracks."

He is open to many genres, except techno, "Too monotonous." And although he enjoyed the social commentary of early rap, he says, "I don't have any hip-hop in my collection. Most of the time, I don't understand what they are saying, so it could just be that. My son likes it, it's the music of his generation." And Idaresit has hipped him to artists like Kendrick Lamar, who he says, " is offering more than just self-aggrandizing."

Victor Ekpuk, Ode to Joy, 2014 interprets Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” Symphony No. 9 in D Minor, Op. 125, "Choral": IV. Finale, Paint markers on wall, site-specific drawing, 144 in x 197 in at the Arkansas Arts Center. Video by Travis Mosler

He mentions that on the ride in from his Alexandria, Virginia home, he listened to “Be Cool,” by Tierney Sutton featuring Al Jarreau. "Very simple, jazzy. I do jazz, a lot of Nigerian tunes, and traditional indigenous music like Chinese strings. My music taste goes everywhere." This brother of the Niger Delta has a fondness for the blues of the Mississippi Delta."The lyrics are quite funny. Everyday folk talking about everyday things." Lightnin' Hopkins and John Lee Hooker each sang about the mojo hand. "The way people make charms to keep men away from their women, that is totally based on African religion. In Yoruba, it's called magun; do not climb." He breaks out in peals of laughter. "Go get some bones to make this magun for your woman so no other man can climb her," he chuckles. "This belief system was transferred across the ocean and is still practiced and believed in." We acknowledge the miracle of African retentions throughout the diaspora. Despite all that was lost in the trans-Atlantic slave trade, so much was not. As an African from the continent now a U.S. citizen living in America, he is a keen observer of the African American community and the palimpsests of culture which survived the Middle Passage.

"It speaks to a series of work that I call Meditations on Memory or Drawing Memory, where I do all these huge walls, and then when the piece is finished, it is then wiped. It exemplifies the notion of memory as an ephemeral condition, or identity as an ephemeral condition always being affected by circumstances. But what is not lost is that the residue stays on the wall – you still see traces of the mark," aligning it with "the persistence of memory of the African Diaspora."

Meditations on Memory performance at Artisphere in Arlington, Virginia, 2012. Pastel. © Victor Ekpuk.

His Meditations on Memory drawing performance for Bienal de La Habana (2015) at Havana’s Wilfredo Lam Contemporary Art Center is, he writes: “an attempt to create a contemporary shrine of memory of the Ibibio, Ejagham, Kwa, Efut and Efik ancestors who were brought in slave ships from my homeland to Cuba. Those whom the great spirit of Ekpe (Ekwe) has protected through the crossing of the treacherous ocean, those whose ancestral memories have been erased only on the surface. Those for whom the siren call of the Tanze (sacred fish) and the roar of the mighty leopard (Ekpe) still calls from across the ocean to dance in the sacred rituals of Abakua.”

Black Panther and Afrofuturism

He gives props to the filmmakers of Marvel Studios' Black Panther for digging deep and bringing a well-researched Pan-African authenticity and aesthetic to the original comic book's fictional Central African nation of Wakanda and its technologically-advanced society. A conceit founded in the truth of Africa's historical knowledge, innovation, and abundant mineral resources. "As far back as the 15th century, when Europe was still in the Dark Ages, bronze was discovered and used in Benin. So perhaps the term Afrofuturism begins to look at the future of Africa as claiming that which always existed," he says. And in the Afrofuturistic vision of the film, "where African technology and knowledge can power the world," it depicts "a place where those things thrive side by side with the humanity that lives there. A place where Africa takes center stage in a way that has never been played out."

"I found it quite brilliant," he says. He is impressed that it incorporates "real African languages,” (isiXhosa from South Africa, and Igbo from Nigeria) “not goobledygook, and the use of ancient African writings as power symbols" seen in Hannah Beachler's production design and Ruth Carter's costumes. "You can recognize actual Yoruba robes. Nsibidi, adinkra and other African scripts that were on their clothing became conduits for power," he says. Case in point, the vibranium "Kimoyo beads" worn on the wrists of many characters in the film as a tool of advanced communication has nsibidi symbols on it.

He was quite pleased to be gifted a replica "Kimoyo bead" bracelet from a friend who knows his fervor for the film. As a proud, Ibibio man, he rocks it enthusiastically. "This is a very powerful amulet. They are using the actual secret codes, which are themselves not just for communication, some are mystical signs. That itself connotes power, and they don't just teach this to everybody."

Residencies bear fruit

He's had artist residencies around the world, which have been instrumental in his development. "I've done several, they give you time and space to think and not be worried so much about everything else going on in your life." On a residency in Lagos, he first embarked on a long-imagined transformation of his drawings into three-dimensional objects. As an artist-in-residence in Santa Fe, he observed the similarities in aesthetics between African and Native American art. For instance, the petroglyphs of the Dogon caves in the Sahara and those of the American Southwest: "You find a similar rendering of geometric shapes, like triangles." He felt privileged to be among the Pueblo people whose ancestors created them.

From the Composition Series, Santa Fe, 2013. Graphite and pastel on paper 50 in x 38 in. (Collection of Fidelity Investments, Albuquerque, NM). From the Slave Narrative Series, Detail of bodies, jumped or thrown overboard in Slave Narrative II, 2018. Pastel on paper 44in. x 50 in. (Collection of the Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College) © Victor Ekpuk.

An Amsterdam residency was the genesis of his Composition series of drawings. "I love to draw, so I used that as an opportunity to explore drawing as its own thing. It also started a theme that I'm still working on called the Slave Narratives." The first in the series is a graphite and pastel drawing now in the collection of the National Museum of African Art. Reinterpreting the famed print of the 18th-century slave ship, Brookes' cramped hull, he juxtaposed the human bodies in the vessel with yams, which, he says, are cash crops in Nigeria. "You have to arrange yams in a certain way for the next season, so they stay fresh in the barn. That arrangement reminded me of human beings being treated as commodities in a barn, like products, not people. In the background, there are stories, little narratives, so you have to go in close." To further explore the history of the trans-Atlantic slave trade from Africa to the Americas, he secured a Smithsonian Research Fellowship to "examine objects, images, and texts" in the collections in NMAfA and the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Specifically, those "depicting the conditions of slavery and slaves' responses to their circumstances." His goal to add new works to his Slave Narrative series, "an ongoing body of work inspired by the history of slavery."

Union of Saint and Venus, 2012. Acrylic and rhinestone collage on wood panel 41 in. by 71 in (Collection of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, Washington, DC).; detail from same. © Victor Ekpuk

When The Walters Museum of Art in Baltimore presented Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe, gallerist and curator Myrtis Bedolla of Galerie Myrtis invited him to respond to the exhibition. He created the powerful The Union of Saint and Venus, recently acquired by NMAAHC, in response to a portrait of Alessandro de Medici, aka il Moro ("the Moor"), the black Duke of Florence born to an enslaved African woman, Simonetta da Collevecchio and Pope Clement IV. The painting is rich with meaning conveyed through multilayered symbols: The pontiff's opulent accoutrements become objects of villainy – his golden crosier, phallic and penetrating, violates the body of Sarah Baartman, the so-called Hottentot Venus. The gems of the papal miter represent pillaged wealth from the vanquished lands and their people. Within the panels formed by the central cross are draconian tools of bondage, slave auction posters, and text from Dum Diversas, the Papal bull issued by Pope Nicholas in 1452. The rambling edict authorized Alfonso V of Portugal to conquer and subjugate Saracens (who professed the Muslim faith), pagans, and all non-believers of Christ, capturing them, their property and possessions and reducing them to "perpetual servitude."

Just as Dutch custom still, in the 21st century, keeps Zwarte Piet, a "servant" of the mitered and crosiered Sint Niklaas/Sinterklaas (jolly old St. Nick) in perpetuity and propels Ekpuk into deeper inquiry for the ongoing series.

Things destined: Asian Uboikpa and Achebe

Immaculata Hart had been a Polytechnic student when she posed for a magazine spread "meant to inform people of the vast Nigerian culture" in the 1970s. Her black and white portrait influenced what would become Ekpuk's Hip Sista (Asian Uboikpa) series on the Mbobo maidens of Nigeria during their rites of passage into womanhood. When he posted the first work in the series and the photo that inspired it on Facebook, a long-time friend exclaimed in response, "That's my mother!" Ekpuk had the opportunity to meet his unwitting muse and share how she'd inspired his work before she passed away.

The first of the series, Asian Uboikpa (Hip Sista) #1 (2014) Acrylic on canvas 48 in x 60 in; the magazine photo that started it all; Asian Uboikpa (Hip Sista) #11 (2014) Acrylic on canvas 48 in x 60 in. Paintings, © Victor Ekpuk. Photos courtesy of Victor Ekpuk.

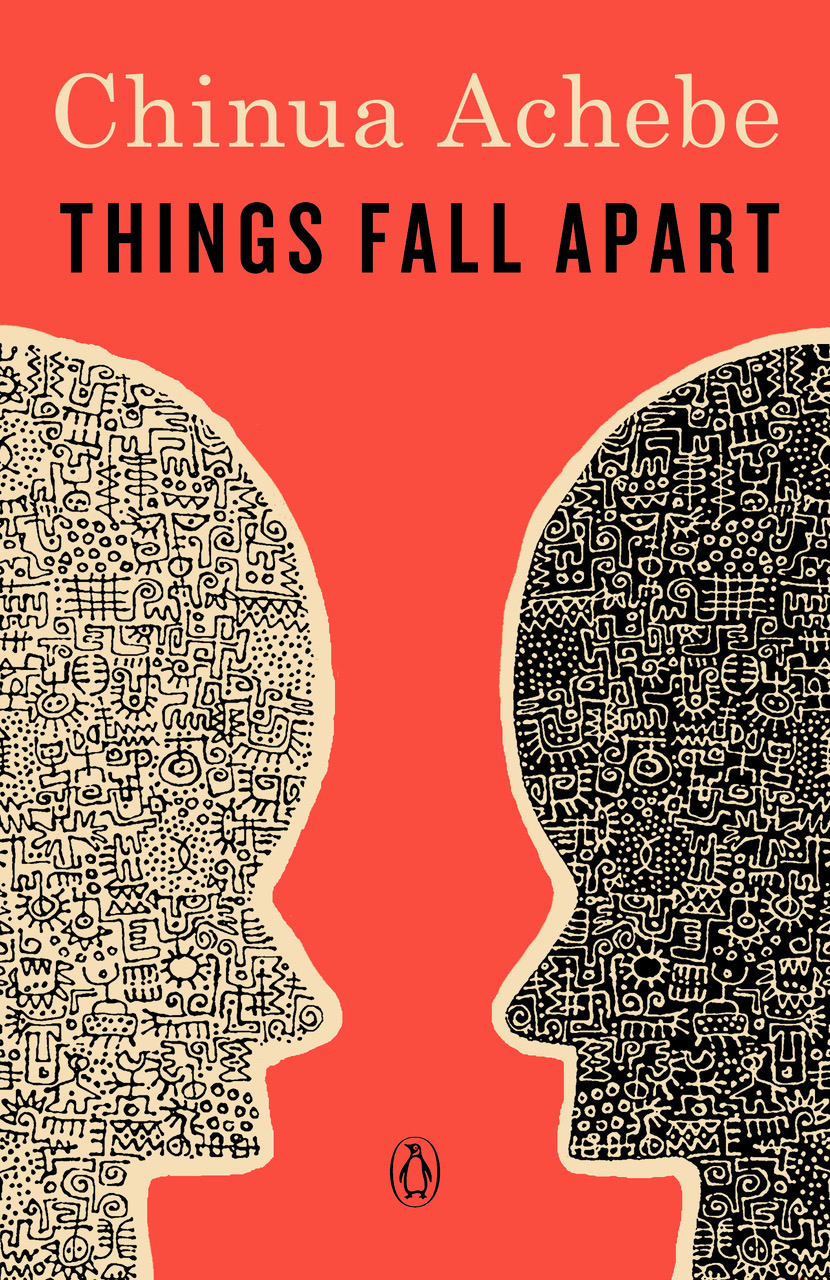

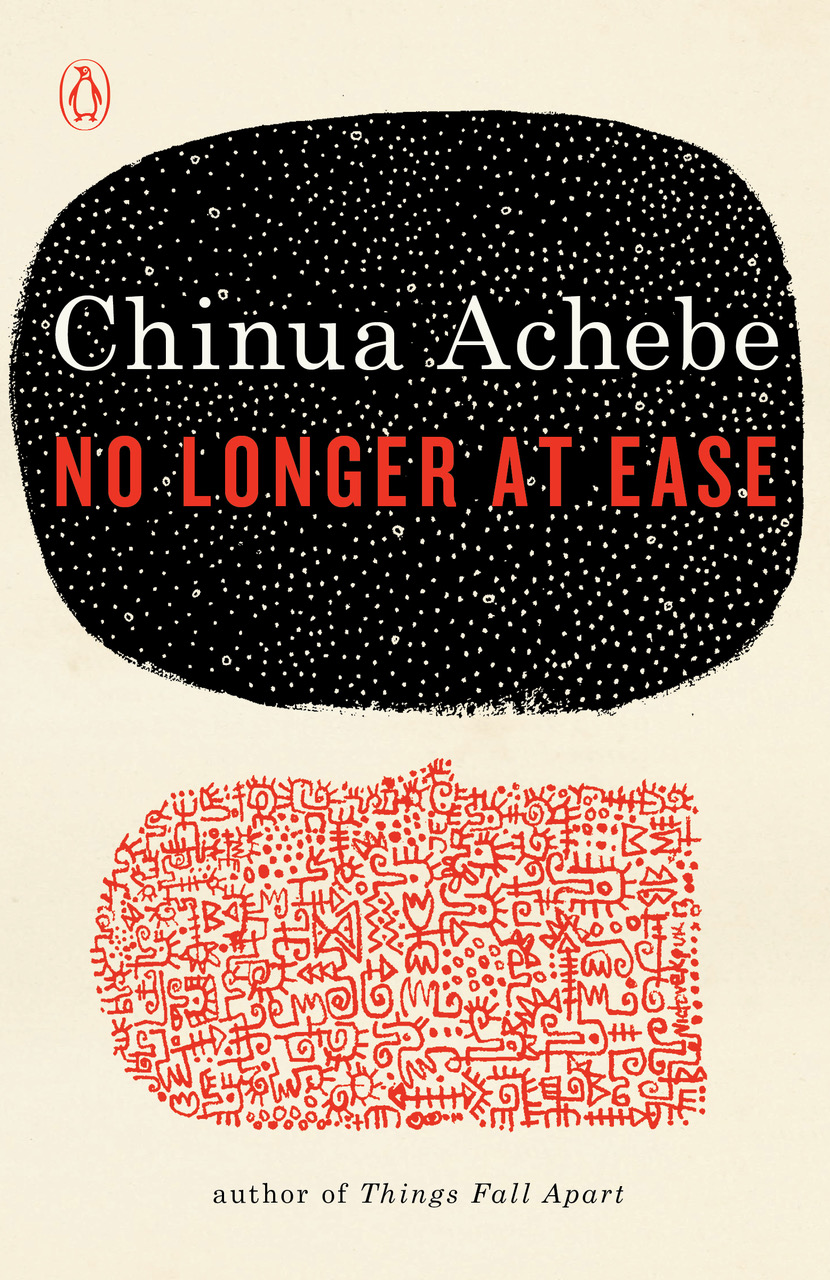

Another meaningful moment of synchronicity happened when his work was chosen to commemorate the late Nigerian author Chinua Achebe's best-known book. "I got a letter one day about the 60th anniversary of Things Fall Apart, and they asked for my work to be used for the book cover. Sure, why not? In fact, it was a huge honor. Nwando Achebe [the author's daughter] said they were planning to reissue the books and were looking for artworks and artists." Of all the works reviewed, the Achebe family made a unanimous decision to choose Ekpuk's 2006 You Be Me I Be You (Acrylic and pigment on wood, now in the collection of The World Bank). He says, "They saw that I, in an artistic way, spoke in the same vocabulary as their father. Themes in my work; everything just worked together."

Book cover art, © Victor Ekpuk. Photo courtesy of Victor Ekpuk.

Of all the titles reissued, Penguin Books only commissioned one cover, for The African Trilogy, the others selected from Ekpuk's existing work. "So it just keeps amazing me that every time a title comes up, I'll go through my work and see a piece that just fits into that title, send it to the family, and they agree. Especially for those drawings I made that echoed what I was experiencing when I was in Nigeria, the human condition, a lot of his stories talk about the human condition. So they're not just artworks that are used for aesthetics only. They help tell the story, rather than a beautiful drawing to put on the cover of a book. He marvels over his collaboration with his esteemed late countryman. "Who knew? Sometimes it felt as if I was reading his book as I was creating the work. So I feel very honored to be included in his legacy."

For a commission at Rocketship Rise Academy, an elementary school in Southeast D.C., Victor Ekpuk derived the composition from an aerial map of the school neighborhood, highlighting historical landmarks, he says, “to bring elements of the community in, demarcating them with color so it became an abstract piece. Dead-end roads blossom into flowers or become hands that reach out to touch others.” © Victor Ekpuk. Photo courtesy of Victor Ekpuk.

The Africa Center

At the northern end of Manhattan's Museum Mile sits The Africa Center, where Ekpuk created a temporary interior mural, Harlem Sunrise, in late 2018. "I'm happy to see them doing things to activate that space," he says. "Africa is present in Harlem. They asked me to come in and do a [wall] drawing, but of course, I got carried away and started doing almost the entire space,” he says, laughing. “I can't see a wall here and see another wall there, and it's not balanced -- it wouldn't look right. Heralding a new day for Africa in Harlem, that was my theme."

As he does in many site-specific works, he incorporates symbols and imagery endemic to the area. In this case, the New York skyline, yellow taxis, and "there's a section of it where I added violence against black males in New York - hands up and crosshairs on the right-hand side." Yet the dominant image is the sacred bird of Yoruba, Osayin, centered in a hopeful sun, the dawning of a new Harlem day.

Early this year, The Africa Center presented him in a sold-out conversation with author Nnedi Okorafor, followed by a book signing for his monograph, Victor Ekpuk: Connecting Lines Across Space and Time. Of the substantial dive into his work by thirteen scholars, he says, "I'm grateful. It is like a retrospective in many ways. It took about three years for it to be realized. Toyin Falola is an eminent professor of African history and a publisher. He has taken an interest in what I do and has decided that maybe I deserve something like this. He pulled together the scholars and asked for essays about different aspects of my work." The result is a full-color, hardbound book beautifully realized with crisp photography offering a rigorous exploration of his oeuvre, including his eloquent artist statements. At a comprehensive and image-rich 489 pages, it's quite a book to behold, engaging more than the academic observer.

Victor Ekpuk and fellow artist Ghada Amer beneath Harlem Sunrise at Teranga, a cafe within The Africa Center. Idaresit Ekpuk beams as his father’s Eye See You looms behind him at the Smithsonian Arts + Industries building. © Victor Ekpuk. Photos courtesy of Victor Ekpuk.

A whirlwind of work

For Halcyon's arts festival, By The People in June, Ekpuk's Eye See You, installed at the Smithsonian's Arts + Industries Building, tumbled 18 feet from above, commenting on this era of omnipresent surveillance and culminating with an artist talk with curator Jessica Stafford Davis.

Although the genesis of his sculptural work is in his 2016 Lagos residency, 2019 heralded his foray into monumental sculptures: the first, Prophet II, six feet tall, included in the Aicon Gallery installation in New York. The second, Hope and Dream Under Glory, a public commission revitalizing Lawrence E. Boone Elementary School in Southeast D.C., rises 20 feet. He was gratified to help transform an environment of brutalist architecture and fluorescent lighting that "felt like a correctional institution; claustrophobic," to something "much more humane; a beautiful campus, airy and just lovely," he says. "I was involved with the design of the landscaping. My work is in the four-way crossing, so it's really for the community, not just for the kids." A plaque, inscribed with his words reads, "Like the ancient Iroko tree, holding up its branches and proclaiming, 'I am still standing, my roots are deep, I have no fear of the wind...'" That the school mascot is the Black Panther aligns perfectly with his intention. In a press statement for the unveiling, he says, "In the African culture that inspires my work, the power of the feline spirit is encoded in secret symbols and graphic signs called nsibidi. By weaving together the mystery, power, and history of the black panther with the vibrancy and spirit of the children of Boone Elementary and their community, this sculpture is designed to visually stimulate, inspire, inform and challenge the imaginations of young minds. It is my hope that this sculpture will perhaps be part of a broader conversation about the history of Africans in America, I am honored for the opportunity to contribute to the memory of a community."

Hope and and Dream Under Glory, 2019, 20 ft. by 10 ft., painted steel. the largest outdoor sculpture in Southeast D.C. Dedicated to the Bahraini people, The Face, 2019, 17ft. by 14ft., painted steel. Sculptures © Victor Ekpuk. Photos courtesy of Victor Expuk.

After a successful showing at Art Dubai in spring 2018 – his first in the Middle East, and the Beirut Art Fair that fall, he received a commission from Bank ABC (Arab Banking Corporation) for its world headquarters in the Kingdom of Bahrain. Unveiled to acclaim in late November 2019, The Face, as Ekpuk says in its inscription, seeks to "capture the essence of a people whose history is long and culture layered in centuries of civilizations." How? By looking to "their beautiful faces hoping to catch the essence of their memory." Painted red, the dominant color of the Bahrain flag, the stainless steel sculpture is at 17 by 14 feet, the largest outdoor sculpture in Bahrain today. (View the unveiling here.) This major, international commission brings a climactic end to an already stellar year. After a Lagos book launch and his Middle East sojourn, he is grateful for the bounty, but the intense travel and physical and mental demands of his work are taxing. He’s glad to return to his family and the relative quiet of their Northern Virginia community. “I like waking up in the morning and hearing birds singing.”

Victor’s TROVE:

1. Apple Pencil. A lover of all things Apple, he says: “I’m a fan. The classic one, I remember opening the package when I got it from the post and the packaging was so beautiful. It was a whole ceremony to unravel it and then you got to the prize. Yes, my Apple Pencil is personalized. I love technology. I’ve come to just love Apple because of how they combine technology and art and produce really beautiful, functional and simple to use objects. I like to draw, being able to draw digitally without the encumbrance [of materials] because sometimes I get my ideas and use whatever is available. I have my iPad, I have the software to make sketches and so on. That has become one of my tools.”

Photo, left © Victor Ekpuk; right, the artist in Sicily. Both photos courtesy of Victor Ekpuk.

2. African Art. “Blue is my favorite color - there’s a spiritual quality. Finding it on ritual objects means they connote some spirituality. This figure by a Senufu artist is one of the objects in my art collection.”

3. Scarves. “I collect handmade scarves by indigenous peoples. I am at the moment partial to the blue Tuareg scarves; they dip the ends. I couldn't get enough of the different shades of blue at the souk in Marrakech.”

© Victor Ekpuk.

4. LUMIX cameras and vintage lenses. “One of my hobbies is photography and lately I’ve gotten into antique lenses. Even though it’s a modern, new camera, LUMIX, it has these Russian antique manual lenses. It’s a very wide lens and sometimes the bokeh is very different from what you find in a correct digital camera. I like the process of just being able to take the time to frame a photograph and adjust. I ask my wife to pose for me, she’s like It’s not done? This is a manual camera.” He laughs. “You have to turn the lens to focus.”

5. Chinua Achebe. His favorite writer. “The way that he is able to tell the African story in a language that uses English but is crafted in a way that no matter what native language you speak, it seems like he is speaking to you. That’s how it appeals to me. You can feel the experience, no matter what cultural background you come from. I read it when I was a kid in Nigeria. Achebe is Igbo, I’m Ibibio, but it didn’t seem strange. It wasn’t foreign to me. His use of words, language, all the proverbs, and so on as African elders speak. In some of the nuggets of truth that he was saying, he was able to bring out and present African culture in a way that is intelligent compared to what white writers and anthropologists have written — especially Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. Things Fall Apart was a response to Heart Of Darkness. So you find a culture – it has poets and singers and writers and people who strive to do good. People who have a conscience. When the tragic hero, Okonkwo took it upon himself to participate in the ritual killing of the boy as decreed by the oracle, a wiseman cautioned him not to participate: he calls you father. This is a moral dilemma for a man solely driven by his toxic masculinity to the point of killing his adopted son whom he loved because he was ‘afraid of being thought weak’. By so doing he disregarded his own conscience and traditions of his people. His life was never the same after that. The brilliance of Achebe is how he uses his characters to interrogate traditional beliefs and customs and finds human responses to them.”

© Victor Ekpuk.

6. Watch collection. “They’re not expensive watches; I just buy them for their design. Sometimes they are very contemporary designs and sometimes it’s construction. I have from Seiko to Citizen to Issey Miyake and Swatch. I put a mark on how much they should be; none above $500,” he laughs. “Above that I’ll look at it; admire it, but I won’t get it.”

He purchased the piece on the left at a fundraiser to benefit the collector (now in a care facility) with whom he exchanged work years before. “It’s nice to have it back in my collection. It’s a beautiful object [the original walaha ] to begin with, but I wrapped copper around it and it is covered in goatskin.” Right, Untitled, 2004 Acrylic on wood 15 3/4 x 7 1/4 x 1/2 in. (Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art., Washington, DC) © Victor Ekpuk

8. Manuscript Series. The statement which accompanies his reconfigured prayer board in NMAfA’s collection says it all: "The idea to use walaha [Qur’anic writing board] as an art medium first struck me in 1995, at a market in Jos, Nigeria, where I saw unused boards on display for sale. I was attracted to their unique shapes, and I was also fascinated by the ingenuity of African aesthetics and how it added meaning to Arabic scripts; I began to see how these boards could tell other stories and bear other meanings. My vision of the potential of the board as a bearer of two important elements of African spirituality and literacy was so strong that, I could not get it out of my head until it was realized. Works in this series are called 'Manuscript Series’ and though executed on walaha, do not make statements about Islam; rather they are an intercultural marriage of form and script. Instead of Arabic scripts, I employ Nsibidi signs and my own script-like drawings to make compositions with themes that center on the human conditions of joy, pain and hope. I try to manipulate the materials so the mystical essence of the board and that of Nsibidi signs are retained. The goal being to create contemporary sacred tablets whose verses tell our stories, hold our prayers and perhaps provide healing and inspiration to us."

© Victor Ekpuk

9. Victor Ekpuk Connecting Lines Across Space and TIme. “It is my very first monograph about my work. It takes the history of what I was doing in college forward. I feel very fortunate that thirteen scholars got together to contribute to the book. That doesn’t usually happen, so yeah It’s a very important book in my career at this point in time.”

10. Fela Kuti. Though the breadth of his musical taste is vast, one of his favorites is the AfroBeat pioneer, whose Afrika Shrine was along the road to his high school in Lagos. "You'd see people outside smoking; everywhere smelled of pot," he laughs. He didn’t dare go in until he was an adult. "Coming from a conservative society like Nigeria's, our parents warned us about Fela, but everyone listened to his music. Who wouldn't like Fela? He spoke truth to power in the real sense of it and he would never cower, even with a gun to his face. Apart from the social commentary, he was such a good composer: the art, the composition, the arrangements.”

Find Victor Ekpuk on Facebook, Instagram, & Twitter and Victor Ekpuk Limited Editions at vekpuk.com and Instagram