Terri Lyne Carrington photographed by Tracy Love.

By Sharon Pendana

It's the third day of October and professor of percussion, Terri Lyne Carrington has the rapt attention of graduate students at her alma mater, the Berklee College of Music in Boston where she is now Zildjian Chair in Jazz Performance at Berklee Global Jazz Institute. Her impressive skills and accomplishments, compassion for the students and passion for the music, make hers among the most sought-after courses at the school. "For me, it's always a dialogue," she begins the seminar-style Forum class. "You can jump in; I’m just sharing some ideas." Ideas that free fall, seemingly disparate, on a circuitous path to an interconnected whole greater than a discussion of music; a distillation of essential truth.

She shares a valuable lesson from legendary saxophonist and composer, Wayne Shorter that forced her to look within. In her early twenties, she completed several European tours with him. "Back then, four-star hotels in Europe could be sketchy," she says. Having heard her multiple complaints about her hotel accommodations, Shorter said, "You need to challenge your complaining nature." She hadn't viewed herself as a complainer and his observation "really changed me," she says. She realized the value in "accepting your environment instead of letting these things outside of you, affect you." Excepting, of course, untenable instances of danger or injustice. "I started looking at things differently, and I became a better person because I challenged this one part."

She encouraged the students to "use this year not only to become better musicians, but also just to become better people. Who you are as a musician is who you are as a person and vice-versa." To study at Berklee at the graduate level they already have to be good players, so what now? "Now the issue is what's going to set you apart from somebody else? What is it about you, about your music that makes the listener care? I challenge you to really think about your purpose. You want to be someone who is striving to make a change. Use your artistry to speak

"All these things make you a better musician," she continues. "When you think progressively, you keep widening your space, fighting boundaries. When you hear somebody amazing, and they can play one note, and you can hear their whole life in that note, that’s because you hear not just their life, but the tradition and beyond. You hear all these years of practice. You hear all these years of long tones. You hear all the years of rudiments, all in a single note. That’s what you’re striving

A cross-section of recordings on which Terri Lyne has served as leader, producer, composer, arranger or session player, including, TLC and Friends, alongside George Coleman, Kenny Barron, and Buster Williams, with her dad, Sonny Carrington

She speaks candidly of the "struggle and hustle" in the field, prompting a student to ask, "So why did you choose a career in music?" She replies, "I think it chose me, more than I chose it. I didn’t know of anything else I wanted. I never even thought about doing anything else. We’re not doing this creative music for financial reward; we’re not doing it to be famous." Nor even "jazz famous," she says, differentiating from Beyoncé-level fame. Though she admits with a chuckle, "Part of me wanted to be Diana Ross when I was growing up. I don’t know if I need a wig and a gown, but I identified with something in her; then there was something that identified with (fellow Leo) Mick Jagger, so go figure. They were both front people and bonafide stars. But then, there’s the part of me that doesn’t want to move from behind the drumset."

"I think you’re driven to do this," she continues, adding that realistically, "Everybody’s not going to have success in the same way." It may not be

She told the mostly male group of students that "Women playing music have had to learn mostly from male instructors. It is important for young male musicians to learn from a female instructor. You know who pointed this out to me? Danilo (Pianist and Artistic Director of

A student who'd studied with Laurie Frank and Ingrid Jensen responds that he's glad she brought up learning from a female instructor. "For me, as a trumpet player, it just opened up this whole other world. That trumpet doesn’t need to be what it’s been."

Another student asks about Terri's spiritual practice, and she shares that though her foundation is in Soka Gakkai, the Buddhism of Nicheren Daishonin practiced by both Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock and the teachings of Pema Chödrön and Thich Nhat Hanh. She adds, however, that she's "not closed off to anything. I rock Joel Osteen in the car all the time. I listen to him at least three or four times a week." Yet another asks what she reads. "Specific books? Anything Joseph Campbell."

Having waxed rhapsodic earlier about "Unfolding," Wayne Shorter's "a-ma-zing" new piece, debuted at the Monterey Jazz Festival, she shares a saying, “Trust that the universe will unfold as it should. Or in Buddhism, it would say Be in rhythm with the universe, which I like." And with a reading of the Desiderata she closed out the class, bidding them "go placidly amid the noise and haste," doubtless that "the universe is unfolding as it should." This is met with enthusiastic applause. Many of the students give their hearty thanks and comment on how deeply the afternoon's talk resonates.

For the next hour, the five students of the Ensemble class receive direction and feedback from Terri and her colleague, Rick DiMuzio as they prepare for their November gig in New York at Dizzy's Club Coca-Cola as the Berklee Global Jazz Ambassadors. They are trumpeter Andrew McAnsh, alto saxophonist Jonathan Suazo, pianist

Matt Carrington, Jr.

Professorial duties complete for the day, Terri and I head for sushi and conversation at nearby Basho Japanese Brasserie. She knows the

She's been a musician nearly as long as she's been alive, so we start at the beginning. In February 1965, drummer

Her musician father played tenor and alto sax with local bands and visiting musicians who came to town. Any jazz artist that rolled through Sonny Carrington knew. It was with multi-instrumentalist, Rahsaan Roland Kirk that Terri, at age five, had her first stage performance, shaking a tambourine and lending her voice to "Volunteered Slavery." Around the same time, she picked up her dad's alto. Her skill on the horn nearly her size, she says, was less than stellar "but I was finding the notes that were in tune with the song if a record was on. Then I lost my first set of teeth, and I couldn’t grip the mouthpiece anymore." She was seven.

Her father, who would periodically play his late father's drums stored in the family basement, allowed Terri to give it a go. She was able to keep

Clockwise from left: Little Terri the budding saxophonist before losing both her baby teeth and her embouchure; sitting in with Oscar Peterson on piano and Keter Betts on bass; all

"I started jamming with people when they would come to Boston. By the time I was eleven, I had jammed with Dizzy Gillespie, Clark Terry, all the drummers: Buddy Rich, Louie Bellson, Roy Haynes, Art Blakey, Elvin Jones. Tons of people in jazz: Les McCann, Grover Washington, Jr., Illinois Jacquet, Sonny Stitt, Rahsaan. You know, B.B. King—my dad really knew everybody. I can never thank him enough. I think it's important to recognize when a parent really does go the extra mile for their kid’s interest; it's a big deal. Because there are sacrifices made. So I’m grateful for my Dad's sacrifices. I would never have the career that I have if it weren’t for him. I had such a great start—of course, there had to be some talent to back it up— but geographically it was in my favor. When they came here they’d let me play a song or two," she says. An opportunity unlikely to have happened in New York, she adds. "Everyone wouldn’t have let an eleven-year-old girl sit in and play with them." Being enmeshed in it so early on precluded the intimidation she may have felt had she started later. "I didn't even realize that it was odd for a little girl to play the drums. I was lucky in that way, to escape any misogyny that may have been going on."

While America celebrated its bicentennial, eleven-year-old Terri's prodigious talent garnered her a full scholarship to the prestigious Berklee College of Music and her union card in Boston, the youngest at the time to receive either. After sitting in with Clark Terry one evening she mentioned that she'd be going to the Boston Globe Jazz Festival the next day; Terry told her to say hello to Oscar Peterson for him. Taking her mission seriously, she waited in the wings to share Terry's greetings after the show. "I walked up to him and said 'Clark Terry told me to tell you hello,'" she said, surprising Peterson. When she shared that she'd "played two sets with Clark the night before," he said, "Well then you have to play with me." As serendipity would have it, the founder and then-President of Berklee College of Music, Lawrence Berk and his wife, Alma witnessed the impromptu set with Peterson and offered her the scholarship on the spot. In an April 1977 feature on Terri in EBONY magazine, Berk is quoted as saying "I think she's genius material."

When that 11-year-old genius toured the Avedis Zildjian Company as its youngest endorsing artist for their famed cymbals, little did she know that she'd one day have a Zildjian scholarship endowed in her name for young women at Berklee. Or that in 2008, she'd design a Zildjian K Custom high definition ride cymbal or Terri Lyne Carrington Artist Series Drumsticks bearing her signature.

Top left:

She'd gotten used to receiving attention for her playing, so she didn't quite grasp the magnitude of the scholarship. For her parents, however, it was a boon, knowing that their daughter's college education was secured before she even left elementary school. In retrospect, she realizes she had a "very interesting, unique childhood," that the duality of her life was a bit different from other children. But at the time, she just felt like a "normal kid," a Girl Scout into skating, Michael Jackson and Earth, Wind & Fire. Yes, she was

She started weekly classes at Berklee with drummer Keith Copeland and piano and theory with pianist Dean Earl. Acclaimed drummer and esteemed instructor Alan Dawson had "developed the drum program at Berklee," and had taught Tony Williams, but was by then teaching privately. Known for his Rudimental Ritual, "he was the greatest drum teacher ever," Terri says. In a Percussive Arts Society posthumous tribute to him Terri said, "When I started playing drums at age seven, he refused to teach me until I was fourteen for fear that his discipline might discourage me. I didn't realize until many years later how compassionate this was of him."

By high school, she encountered some petty jealousies from other students, but they were fairly innocuous. She went on to graduate a year early, at sixteen, third in a class of one thousand. In spite of her guaranteed, full-ride to Berklee, guidance counselors encouraged the honor roll student who excelled in math "to apply for scholarships at Ivy League schools, like they were saying you can do better than going to a music college," she says.

Through the years. Photos courtesy of Terri Lyne Carrington, except second image, top row, EBONY magazine, Johnson Publishing Company.

Interestingly enough, she attended Berklee for only three semesters, studying composition, arrangement, and theory before leaving, at the urging of Jack DeJohnette, to give New York a try. She landed in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, sharing an apartment with M-Base member and Berklee alum Greg Osby during a time of cultural Renaissance in film, art, and music. She packed in a lot during those early years, leveraging the contacts she'd made over the years and her remarkable prowess on the instrument. Among the many artists she worked with are James Moody, Lester Bowie, Pharoah Sanders and Clark Terry, who once again provided her with another incredible opportunity, his 1984-1985 European tour. In 1986, she had her New York solo debut at Symphony Space. Then she beat out dozen or so drumming hopefuls for Wayne Shorter's touring band, beginning a lasting working/mentoring relationship. She appears on his 1988 release Joy Ryder, noted for its balance of male and female personnel with Geri Allen, Patrice Rushen, and Dianne Reeves also appearing. She became the first drummer for the Arsenio Hall Show house band, The Posse, led by Michael Wolff, then moved to Los Angeles. The following year she released her major label debut recording, Real Life Story with some heavy-hitting personnel: Carlos Santana, Grover Washington Jr., Wayne Shorter, Patrice Rushen, Gerald Albright, John Scofield, Greg Osby, and Hiram Bullock. She left "The Posse" to properly promote it, and she got the opportunity to do so on the show before leaving. She also received a GRAMMY® nod for this first outing, which was, of course, thrilling, but she didn't expect to win—ultimately Pat Metheny did. But it was the start of her career, and it would happen again, or so she thought. Even after the success of the recording—selling 100,000 units—it was difficult to secure a deal, "which is why it was so disheartening not to keep

In the interim, her talents kept her in demand on other artists' projects, whether recording, producing or touring. The high point of touring with Al Jarreau in 1993 was performing at an African National Congress fundraiser for Nelson Mandela's presidential run. It was an exciting time to be in South Africa, on the precipice of pivotal change. But on the micro level, it was in observing the personal camaraderie between Zuzi Buthelezi, whom she'd befriended and Zindzi Mandela. The son and daughter respectively, of political rivals Chief Buthelezi and Nelson Mandela, were the best of friends, which spoke volumes. They put aside talk of "fighting and the enemy."

A rising drum star: in triplicate for People Magazine; performing "Human Revolution" from her debut album on Verve Forecast, Real Life Story

In 1996 she co-produced "Always Reach for Your Dreams," sung by Peabo Bryson and commissioned by the Atlanta Olympic Committee for the Atlanta games. Another television opportunity surfaced in 1997, Quincy Jones' late-night talk show companion to the magazine Vibe. Once again the house drummer, now sporting locks with her bright, warm smile, she kicked it with host Sinbad and company for a year. A notable session of the period includes Herbie Hancock's GRAMMY® winner, Gershwin's World (with Joni Mitchell, Stevie Wonder, Kathleen Battle and Wayne Shorter). She started a decade of touring with Hancock's various acoustic and electric groups.

Which brings us back to the German label, ACT, which released Jazz is a Spirit in 2002, with excellent liner notes by Angela Davis and then Structure in 2004, a collaboration with saxophonist Greg Osby, guitarist Adam Rogers, and bassist, Jimmy Haslip. In a 2003 full-circle moment, twenty years after his father offered gifted schoolgirl Terri a Berklee scholarship, Lee Eliot Berk, namesake and president of the Berklee College of Music, presented her with an honorary doctorate from the school.

Because of her father's integral role in her career trajectory, she speaks quite frequently of him, however, her admiration for her mother is boundless. Before Terri was born, Judith Carrington was a

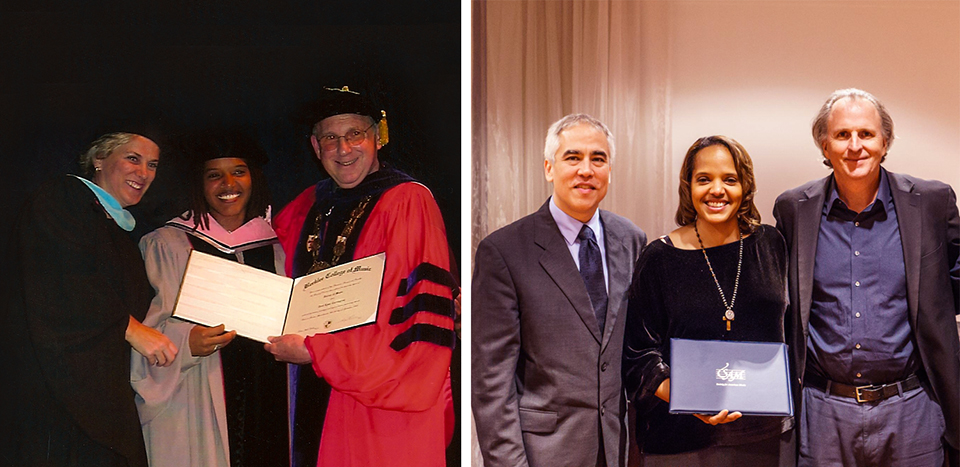

With Honors: Craigie Zildjian, Avedis Zildjian CEO joins as Lee Eliot Berk, then-President of Berklee College of Music presents Terri with an Honorary Doctorate. Photo courtesy of Terri Lyne Carrington. Charles Garrett, President of the Society for American Music (SAM) and Roger Brown, current President of Berklee College of Music flank SAM honoree Terri. Photo: Michael Broyles

It goes without saying that her parents have, but when asked about people who've inspired her, Terri replies, "It varies, depending on where I’m at in my life. I was inspired by my drum teacher Alan Dawson—the greatest. He was more of a disciplinarian; I’m a little softer. I can’t say that I had any other teacher that inspired me to that degree, but I’ve had plenty of mentors. On the drums, as a drummer/musician/artist, Jack DeJohnette was a big mentor for me and

During the Forum class, she spoke to her students about keeping a seeking spirit, "yearning to see the Buddha. The Buddha could be whomever, but it’s someone who knows a little more than you about something. So for me, if somebody asks me enough times to have a coffee, I will do it. If they ask me once, I might not, because I have a million things to do. But if they ask me enough, I know that they are seeking something and that was what was done for me. That’s what Jack DeJohnette did for me." She made the tedious trek to his mountain home thinking, Oh my God, will I ever get there? And when I get there, he says 'yeah, I know that the people who come to see me really want to see me.'" He never gave her lessons, but they'd talk about and listen to music.

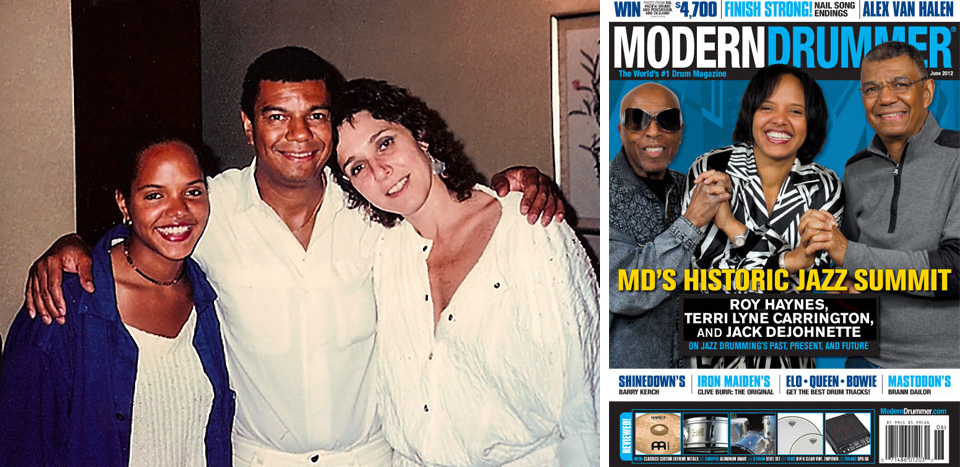

With Jack and Lydia DeJohnette. Photo courtesy of Terri Lyne Carrington. A trinity of greats

"I don’t think we have as much crabs-in-the-barrel syndrome in jazz because everybody is an underdog, you know. Generationally and traditionally, the elder musicians have supported and mentored the younger musicians because they care about the music; because that's the only way the music will continue," she says. "You do this because you love it; you don’t do it to be a star. That may be the biggest difference between jazz and other genres. Which innately, I think, creates more mentoring."

Wayne Shorter is a musical and spiritual mentor. She speaks of him frequently. "He introduced me to Buddhism and overall, he’s a genius. So anytime you are around a genius, something rubs off. You’re inspired by that. At the Monterey Jazz Festival, I was an artist-in-residence this year, and he did a new piece with the large ensemble. It was so inspiring. To think that somebody in their eighties is just knocking it out the park as a composer and player and person, how can you not be inspired?"

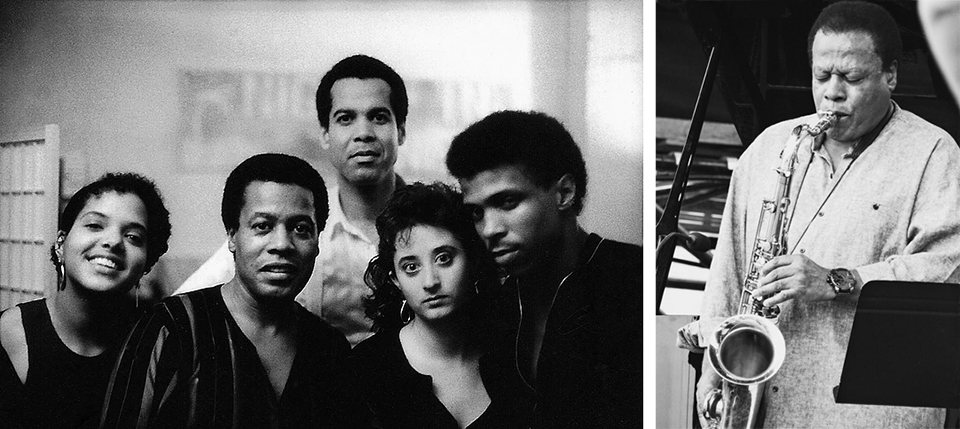

Terri Lyne started touring with Wayne Shorter shortly out of her teen years. Photo courtesy of Terri Lyne Carrington. The NEA Jazz Master performs for his 80th birthday at the Newport Jazz Festival. Photo: Sharon Pendana for THE TROVE.

Though Terri has conducted drum clinics and workshops since high school, she didn't become a college instructor until 2005 at

The familiar plunk of a xylophone and sounds of baby joy that intro the grooving "Dorian's Playground" on Terri's fourth album, More to Say (Real Life Story: Next Gen) truly touches on her reality at the time. Her sweet baby is now ten-years-old, and like his mother before him is learning to play his grandfather's instrument. Terri is happy her father and son can bond over the saxophone. Managing it all is difficult, she says, with her frequent travel. "It’s all about balance. But I feel that children pick their parents' spirits, so I have to believe that some place in him is accepting of it [her travel] even when he complains about it. He’s definitely an old soul. He sees deeply into things. He’s ten going on twenty." It has made her prioritize her focus, "Less going out on the road with something that I’m not inspired to do." Motherhood has made her "even more sensitive than I was before, and I was always pretty sensitive. My heart breaks a little faster; easier. Things touch me a lot more deeply. It makes me want to make everything count that I’m doing because I don’t have time to mess around. So less meandering, more time to get to the point."

"I remember Louis Farrakhan

From personal experience, she knows that music heals. "If I get a headache and I start to play, it goes away. Consistently over my life. It heals on various levels to me." She considers that "people who come to you after performances or write to you and tell you how much the performance was transformative to them on any level shows the power of affecting somebody else’s life. So you start to think, what do I want to do with that?" She recalls a directive from Wayne Shorter before playing a show. "If a woman in a bad relationship comes to the show, I want her to leave with the courage to leave that relationship." And that was the only preparation we had for the show. But it made me think; it’s often not about the notes. The notes are a message you put together somehow you’re transferring a message

Though she's

A young Terri Lyne reads Angela Davis An Autobiography. Now one of Terri's closest friends, Ms. Davis continues to inspire. In the liner notes to Terri's 2002 release, Jazz is a Spirit, she writes that Terri "has significantly transformed the way we think about

She contemplates the messaging in her other releases. I did The Mosaic Project (that I had Angela speak on and she talked about the prison industrial complex on that song with Dianne [Reeves], "Echo." Then I did The Money Jungle which had a lot of commentary about art and commerce, so there was some social consciousness, but I’m trying to do more of that actually. I feel that everything I do from this point on has to really count." Her last record, Mosaic: LOVE and SOUL, an exploration of her vulnerability in love, is all love songs. Sometimes love truly is the message, but she has no plans for love songs on her next outing, a collaborative effort, "with Aaron Parks, piano player, and Matt Stevens, guitar player. I’m excited about doing this with them. They represent part of this newer generation of people that still have a good hold on what’s come before them, but are important to the music and moving it forward. We’ll also have a poet or rapper or MC something like that, a bass player, but the core will be the three of us."

"I was always the youngest person in the jazz world," she says. "Now a lot of people I enjoy playing with are much younger than me. I'm holding on by the skin of my teeth," she laughs her easy laugh. "It keeps me motivated, my ears open to something fresh; something new and that’s a good thing about teaching."

Terri Lyne beams with her first GRAMMY® in 2012 for Best Jazz Vocal Album for The Mosaic Project. She enjoyed subsequent wins for Best Jazz Instrumental Album in 2014 for Money Jungle: Provocative in Blue and in 2015 for once again producing the Best Jazz Vocal Album, Dianne Reeves' Beautiful Life.

Her openness and expansive thinking have served her well. When she realized she'd called several women for a recording date, it set the foundation for the musical celebration of women called The Mosaic Project. Assembling an all-female cast including Esperanza Spalding, Dianne Reeves, Dee Dee Bridgewater, Sheila E., Nona Hendryx, Cassandra Wilson, Geri Allen, Gretchen Parlato and more, she got the attention of Concord Music, her first for the label. She opens brilliantly with Nona Hendryx in a jazzy, mellowed arrangement of her signature tune, "Transformation" and moves beautifully through the 14 tracks, which includes Terri's poignant tribute to her late friend, Teena Marie. Her knack for pairing the right song with the right person is on full display. It is no wonder that it garnered Terri her very first GRAMMY® for Best Jazz Vocal. She felt affirmed for the entirety of her career. Humbly, she says, "I got lucky because that year the people who were on my record were not up for a record. Dee Dee didn’t have a record out, Dianne didn’t have a record out, and Cassandra didn’t have a record out."

Her second win, the Best Jazz Instrumental GRAMMY® was for her ambitious project, Money Jungle; Provocative in Blue, a reworking of the Duke Ellington 1963 classic on its 50th anniversary, featuring Gerald Clayton in the Ellington spot, Christian McBride in the Charles Mingus role and Terri filling in for Max Roach. Christian McBride and Gerald Clayton were also both individually nominated for their own records. "It was tricky, but I won," she says. "That was when I became the first woman ever to win in the instrumental jazz category. I think that was an important win."

On the first one, she made a great record with a superb assembly of women. "And I felt like I had worked up to that point over thirty years, culminating with a recording that had elements of all that I had done. Then the second one was important because of the historical context of the award with women. The third one I won as a producer of Dianne Reeves' record, Beautiful Life. And that was important because producing is as important to me as just playing or writing." Being acknowledged for jazz vocal, jazz instrumental, and producing feels for her, complete. "So if it never happens again, I'm good."

Terri commands attention for both her solo efforts and collaborations such as the ACS Trio with Geri Allen and Esperanza Spalding or the Murray, Allen, Carrington Power Trio with David Murray and Geri Allen.

She wants to shift her output to more composing and musical direction (MD) "I’m not going to have my career, the rest of my life be relegated to me having to go on the road to play. I love to MD projects. I just did a Hollywood Bowl show, which was a tribute to Dinah Washington, Eartha Kitt, and Lena Horne. Vocalists were Patti Austin, Ledisi, Dee Dee Bridgewater and Judith Hill. I’m doing another one in May, a tribute to Abbey Lincoln with Esperanza, Dianne Reeves, and Dee Dee Bridgewater. That’s the Kennedy Center, The Apollo, and the Kimmel Center." Smiling, she says, "I love

TLC with Clark Terry, Wayne Shorter and Carlos Santana, Nelson Mandela, Al Jarreau, Greg Osby and Cassandra Wilson, Herbie Hancock, Wallace Roney, Wayne Shorter, Vibe MD, Greg Phillanganes, Herbie Hancock, Vernon Jordan and Quincy Jones at the White House, Al Gore, performing with Valerie Simpson, Rachelle Ferrell, Lalah Hathaway and Cassandra Wilson and finally, rehearsing for an event at the Thelonious Monk Institute for Jazz with the remaining members of the Second Great Miles Davis Quintet: Ron Carter, bass; Herbie Hancock, piano; Wayne Shorter, saxophone. Photo with Clark Terry, Jet magazine. All others courtesy of Terri Lyne Carrington.

TLC with: Nancy Wilson, Clark Terry & Dianne Reeves, Tipper Gore, George Duke, Cindy Blackman & Sheila E., Kennedy Center Honoree, Herbie Hancock, Nona Hendryx, Patrice Rushen, Esperanza Spalding, Lizz Wright, Ledisi and an artist she's not yet played with but would love to

With a lengthy and illustrious career such as hers, arises the question of what her legacy will be. "It is hard to talk about legacy because it insinuates a

In speaking with Lee Fish after the Dizzy's Club Coca-Cola date, he attests to Terri's inspiration. "It was my first time playing that room. Nice room, nice audience and it was fun sharing it with Terri. It was great seeing how she worked. She's inspiring to be around, great to be around—good energy. She's relaxed, but in the perfect way because she still has the fire too. She's all-around one of the most versatile musicians." As special guest Terri joined the Berklee Global Jazz Ambassadors for a few tunes, Lee was honored to sing a lovely arrangement of "I'll be Seeing You" to close out the show. "The next day we did a high school workshop in Queens. It's nice to be able to give back," he says. "Terri's honest and really humble, and that I admire."

In this season of Thanksgiving, Terri expresses her "gratitude for the amazing life that I am having. I recognize that everybody hasn’t had that good fortune. My parents and my father’s help and tutelage, those experiences that were passed on to me. Some people joke that when you’re born into a family that’s financially rich— that you’ve won the womb lottery. So I feel like I won the womb lottery—it was just a different kind of rich."

Terri Lyne's TROVE:

A few TLC Faves: Missy Elliot, So Addictive; Joni Mitchell, Don Juan's Reckless Daughter (particularly the song "Paprika Plains") Marvin Gaye, What's Going On; Jimi Hendrix and the Band of Gypsys, Live at the Fillmore East; Rachelle Ferrell, Individuality (can I be me?); John Coltrane, Ballads; Shirley Horn, Here's to Life; The Beatles, Abbey Road and Miles Davis, Sorcerer.

1. Music. "Specifically jazz, R&B, and sophisticated indie rock/folk. I like new and alternative jazz, as well as the classics of course, but after the great Miles Davis Quintet of the 60s and the great Coltrane Quartet, it is hard to focus on music of that time period, as it has been done at its best. I love the state of jazz now, where other genres are influencing one’s individual

2. Nature Walks. "When I walk, I am balancing myself and showing appreciation for all that the Creator gives us. Never taking the natural beauty and natural order of life for granted. I love Horn Pond in Woburn, MA." The trailer for Philip Valende's film, The Nature of Horn Pond gives a stunning glimpse of the area's natural beauty.

Chardonnay from the only Black-owned estate winery in Napa Valley, Brown Estate; and one of TLC's vegetarian specialties, Tofu Stir-Fry.

3. A glass of fine wine. "I like white wine these days, Sancerre or Chardonnay. I used to drink only red, but a lighter wine is working better for me now. I like trying different brands. I also like Rosé—recently tried Navarro Rosé and like that a lot."

4. Cooking. "I like to cook because I find it therapeutic and creative. I am a recent vegetarian—some days vegan—so I have to get better at these dishes."

After living in New York and Los Angeles, Terri Lyne returned to her Boston-area hometown to be near her beloved parents, Judy and Sonny Carrington, and join the Berklee faculty. Some of her most treasured moments are spent at family gatherings. "Nothing like spending time with family," she says.

5. Love. In all its permutations, agape, familial, romantic...One of her many tattoos is the word 'love,' written in Sanskrit. "When we are truly expressing love to another, we are acting from our highest self, it brings the best out of us and the goal is to stay at our best in all areas of life. It is inspiring and fulfilling, especially love of self, love of God—or whatever one calls it—and love of life."

6. Watches and Rings. She's partial to Swiss-made TAG Heuer watches and loves diamond rings. "Maybe diamonds actually are one of a girl’s best friends," she smiles.

7. DeLovely. "This is one of the greatest love stories I’ve seen, and told through the incredible music of Cole Porter. He is my favorite composer of jazz standards, along with Duke Ellington."

The stunning Presidential Suite at Four Seasons Sydney overlooks Sydney Harbour and the Iconic Opera House.

8. Nice hotel rooms. No complaints here. Key for someone who spends a lot of time on the road. "I like Four Seasons, Ritz-

9. Ping-pong. "Table tennis is one of the only sports I excel at. It feeds my competitive nature and is just a lot of fun for me to play."

Photo by Tracy Love.

10. Eating Orange Leaf

Follow Terri Lyne on Facebook, Instagram @terrilynecarrington, Twitter @tlcarrington, and watch all her great videos on YouTube