Jimmy James Greene photographed by Sharon Pendana for THE TROVE.

In his tidy Hamilton Heights apartment, artist Jimmy James Greene has created a haven from the boom and bombast of city life and in these uncertain times, respite from the ideological noise. Just as esteemed playwright August Wilson through his encounter with Romare Bearden’s The Prevalence of Ritual was emboldened to depict African American life in its lush richness, so too was Jimmy inspired by the

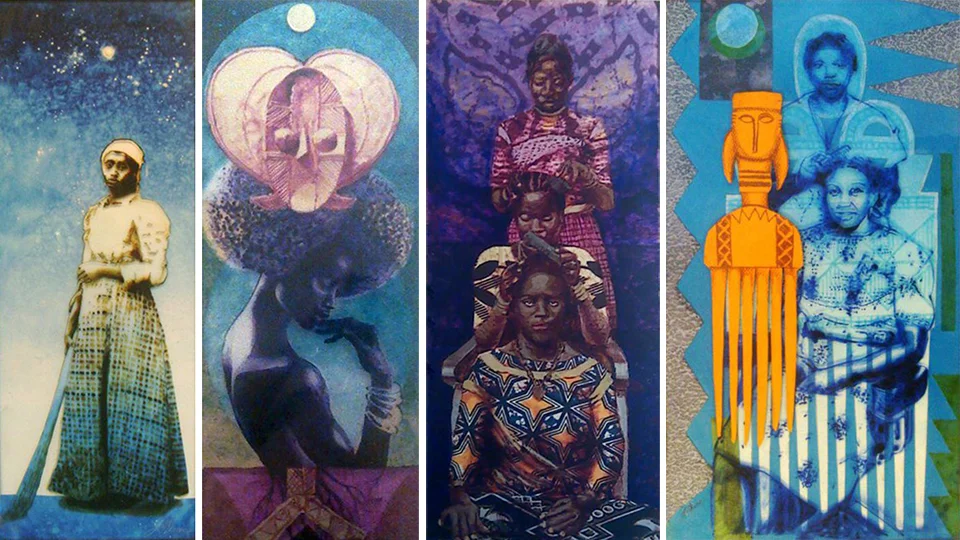

Processions recur in his work: cultural ritual, rites of passage, communal movement. Mundane activities are exalted: hair braiding and plant tending. A hint of sunlight dapples the room through the

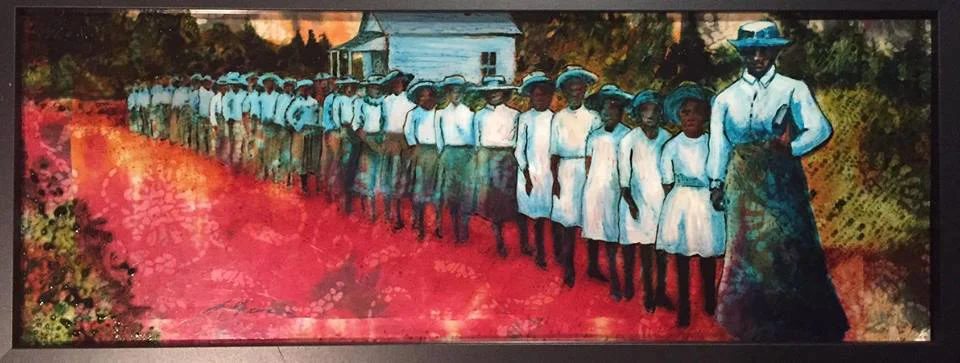

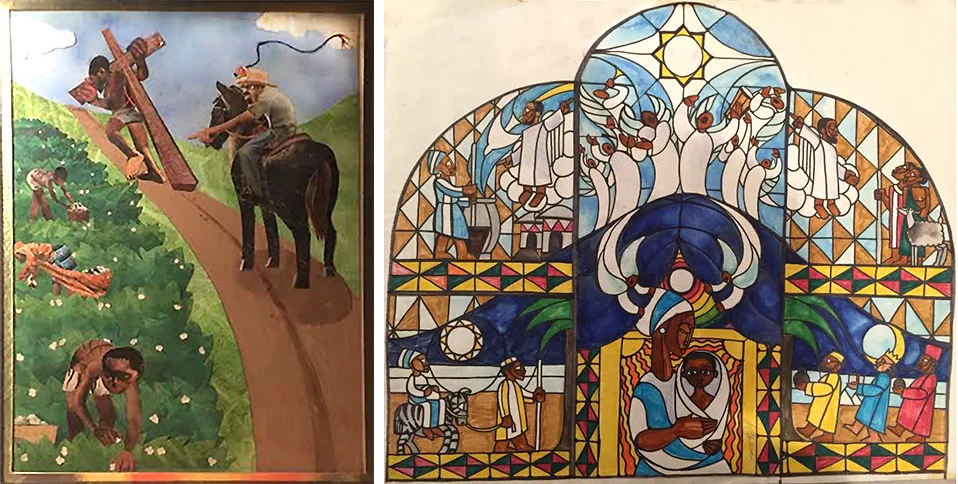

From the Ancestral Layers series, The Teacher, painted plexiglass over collage.

Having known Jimmy Greene for most of my adult life, I've borne witness to his explorations of various mediums. “I kinda backed into Bearden,” he says, describing the genesis of a lengthy "Romarian" romance, the throes of which he was in when we met. “I started doing collage using whole images, pictures from National Geographic and combining them. If I draw, I know what’s going to happen. With collage, a lot of unexpected things could happen with the juxtaposition in the way something’s cut. I just like the way Bearden fractured the images; it was a lot more creative than the way I was approaching it.” Profoundly influenced, Jimmy worked in collage almost exclusively. Although he eventually returned to drawing and painting, the cubistic nature of collage suffuses these works as well. “I started using collage as studies for my paintings. Collage is a composer’s medium; it’s about the way things are put together and organized, and that’s one of the things I enjoy most about doing the art; not making lines and marks, but organizing the space.”

"There were so many different ways that Bearden approached art," he says. "It's hard to do collage and not reference him somewhere. He’s both very free with it and then very tight at other times. He was encyclopedic in his approach. I saw A Black Odyssey (Bearden's landmark series reimagining Homer's mythological The Odyssey with black characters) which is different from, say, the Southern collages. First of all, they’re really big pieces—the other things are very small—you can tell that he’s planned them out. It’s a whole different approach to collage. It was so impressive. He loomed large in my work for a long time."

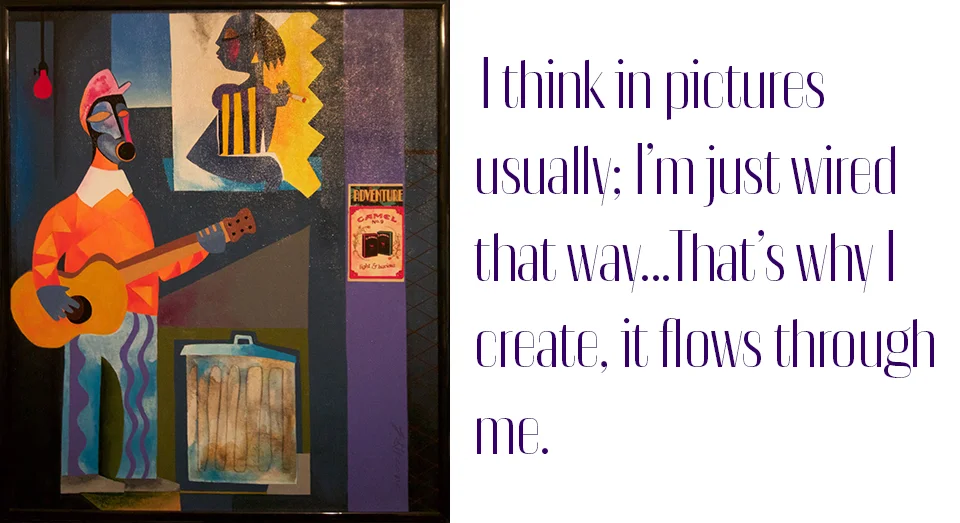

The Troubadour, acrylic on canvas with collage elements.

Xenia, the Ancient Greek concept of hospitality thematically dominant in Homer’s Odyssey just happens to be the name of the small Southwestern Ohio city from which Jimmy hails. The county seat of Greene County (so named for Revolutionary War General Nathanael Greene; no connection to Jimmy’s family), it is said to have been dubbed “the place of the devil winds” by the people of the Shawnee Nation. On the afternoon of April 3, 1974, while watching Gilligan’s Island on television, Jimmy dozed off. At 4:39 pm, as he enjoyed an after-school nap, without warning the devil winds whirled into a treacherous funnel–an F5 tornado–leveling half of the city within minutes. Fortunately, his East End community was relatively unscathed. The Greene's lost a tree and suffered only a broken window.

“I woke up,” he says, “and my sister was like ‘the city just got blown away.’" He didn’t believe her. “A friend came by, and we just started walking. As we came closer to the middle of the town, we saw some street signs flattened out and cars that were turned over.” They found their high school, with buses atop it. “That’s how strong it hit. The scary part was, if it had happened during school time, they would have put us in the gym. And the whole gym just collapsed.” Nonetheless, with the invincibility of adolescence, he climbed through a window to retrieve his art kit. “I had just bought my first acrylic set; I wanted it back. Did that make me a looter?” He laughs. “And since nobody else was

"We ended up going to many schools because they would have to ship us to other neighboring communities, and we went to school in shifts: we would go in the daytime, and another group would come in the afternoon. There was really a lot of confusion caused by that tornado.” Having slept through the horrifying “Funnel of Fury” and its deafening roar, he was spared the first-hand, traumatizing terror of those nine long minutes. Still, it was "a major thing to see how transient, how impermanent, how violent nature can be.

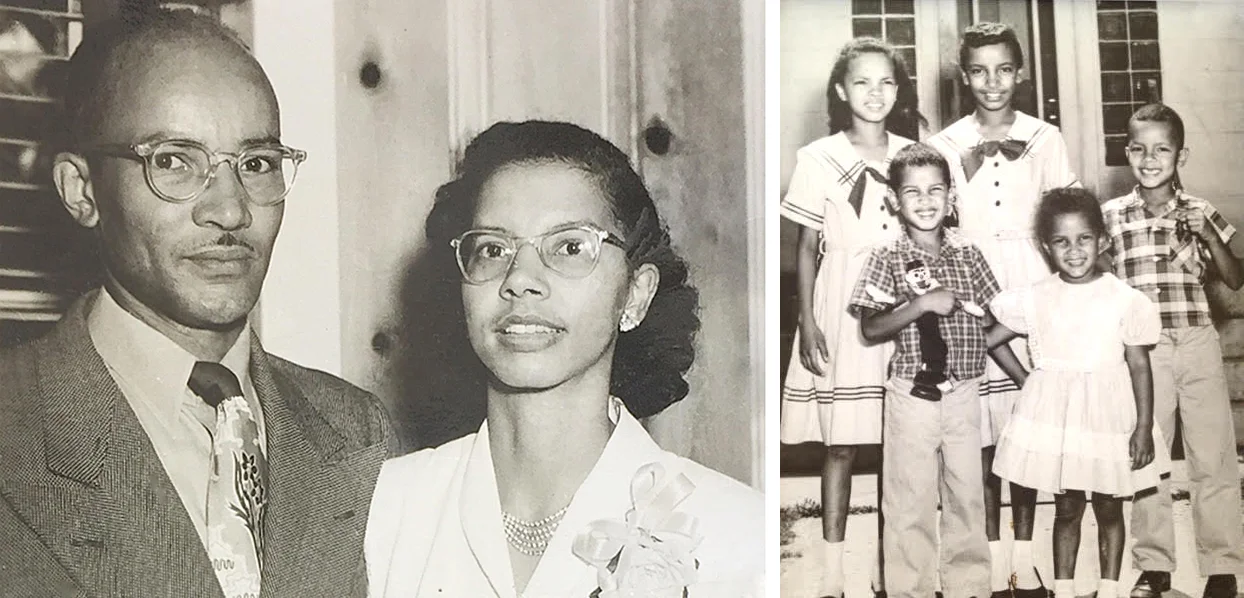

The Greene siblings: (from left) future engineer/city planner, Paul; future blind rehabilitation therapist, Jan; future anesthesiologist, Brenda; future radiologist, Judy, and always artist/musician Jimmy. Photo courtesy of Judy L. Greene.

He and his siblings grew up in a Xenia just beginning to integrate schools. “We were in the East End; that’s what they called the black section of town. I went to an experimental elementary school two blocks away, Xenia Center for Educational Programming (XCEP) from third to sixth grade. They bused in white kids to our black neighborhood." He has no recollection of it being particularly eventful.

"I started playing clarinet in third grade, took lessons. Five kids in the family and four of us played clarinet, the same clarinet.” The instrument was passed from one child to the next. Clarinet practice was a bonding time for Jimmy, his sisters, Judy and Jan (now Aicha) and their musical father who rehearsed them. The girls stopped playing after middle school, but Jimmy continued, also learning recorder, saxophone, and flute. “The fingering is pretty much the same; they’re all woodwinds."

The late-night

His love of music finds its way into his visual art: (left) Monk's Dream and (right) Saint John [Coltrane}, watercolors, colored pencils and acrylics.

Jimmy Hall, Lee Oskar and school integration notwithstanding, “music and racial identity went hand in hand,” he says. James Brown was saying it loud when James Greene was in elementary school. And Dayton, Ohio, just 20 miles away was musically, "where it was at." There was "a definite funk that came out of Dayton." He recalls Something in the Water, a late nineties exhibition exploring Dayton's emergence as the funk capital of the country.

Jimmy came from “a very small world and Dayton was the big city. I remember the first time I went to Dayton; I was like Are they

Back in the East End, "my band, not the school band, but the little play-the-funky-music band I was in was all black—Eastern Express. We weren’t really proficient musicians, I mean we covered the latest songs (from bands like BT Express, KC and the Sunshine Band and Kool and the Gang). "The horn lines were pretty simple stuff," he says. "I didn’t have to be going to Juilliard to be able to play those lines."

Theodore and Juanita Greene. Photo courtesy of Judy L

But his pops, New York-born, Xenia-raised Theodore Brinson Greene, though modest about his prowess on the trombone, nevertheless performed with the Kentucky State Collegians at none other than Carnegie Hall. After serving the US in Italy during World War II, he utilized the G.I. Bill to secure affordable land for the construction of a twelve-unit apartment complex, Greene’s Apartments in Xenia to house his growing family and generate rental income. He and his brother Robert built the homes themselves of cinder blocks, “which I thought was pretty impressive,” Jimmy says of his father and uncle. He realizes in retrospect that the location at the foot of two hills accounted for the low cost of the property. “When it rained, the basements of the apartments would flood. He had to have the sump pumps going.” Theodore managed the buildings in addition to his work as an audio/visual instructor and photographer for nearby Central State and Wilberforce Universities.

His wife, Juanita May (née Porter) worked as a stenographer and proofreader at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base with aspirations of becoming a nurse. Five children later, she became a homemaker. Her medical dreams were fulfilled, however, through her eldest child, Judy, and her baby, Brenda, who both became doctors.

“Mom used to drive us crazy, always correcting our English," Jimmy says. "But it helped in school a lot. You’d stop to think, well what would Mama say?” Mama’s say would allow her youngest son the freedom to explore his interest in music far from the East End. One summer he went to Chicago as part of a band, Mass Production (not the band of the same name which would gain fame

Jimmy, second from left, with fellow members of Mass Production in 1973. The photo appeared in the February 17, 1977 issue of Jet Magazine in an article on the death of drummer, Delbert Patterson, seated front center.

After three months away, he decided to return home—only to discover home was now on a farm. His dad, who owned and coaxed a garden from the plot of land across from their home, had “retired, bought a farm and jetted out of Greene’s Apartments,” Jimmy says. “I couldn’t wait to get home, and they’d moved.” The trombone-playing photographer set down his instrument and camera and became, as Jimmy says “a citizen farmer.” Although he helped on the farm, Jimmy did not share his father’s agricultural passion. “The first job that I had was working on the farm. I hated it,” he shares. “The stereotype of the lazy, dumb farmer, I don’t know where it came from because you can’t be either. If you make a mistake, it could be a big one. It is hard, hard work.” He remembers his father’s talent for grafting: “apples, pears, different fruits coming from the same tree.” His dad was a proponent of self-sufficiency. “He raised chickens, corn, vegetables. He wanted to be able to have a meal that you didn’t have to go to the store to get.” Jimmy recalls his parents’ entrepreneurial bent. “He had this U-pick for the orchard so that you could come, he’d give you a bag, and you’d just pay by the pound. My mother would take a lot of the produce and sell it to the local universities or people in the city. Even at the apartment, they had a

Because Jimmy had maintained good grades, he was able to pick up where he left off during his Mass Production sojourn without any questions, re-joining his classmates at Xenia High School, where a white Kentuckian Rhodes Scholar, Walt Whittaker, taught art. “I still keep in touch with him; he’s in his eighties now,” Jimmy says. “I felt like I was in Paris when I was hanging out at his house in Ohio. Mr. Whittaker was very unorthodox. The first time I met him, I ended up staying over. I became friendly with his son who is now a physicist.” As he shows me a small block print by his former teacher, he says, “He was a composer too, simple shapes, but a kind of elegance to it.”

The original sketch for Cultivate, and the completed stained glass mosaic.

“It makes me think about the things I did as a kid, Colorforms—the abstract ones, which were about composition, and Paint-by-Numbers. I liked to do

Like the tornado, another lesson of impermanence hit hard and unexpectedly. Brian, with whom Jimmy had become “pretty tight” went off to study sculpture at Berea College. The toxicity of the material used in his work proved carcinogenic, and he died of brain cancer. “Materials can be dangerous,” Jimmy says. Never fond of oil paints—the smells, the drying times, the solvents needed, the heavy metals—he sticks to his preferred acrylics.

From his series of painted plexiglass over collage: The Sweeper; Earth, Woman, Spirit; Hair-Line; and The Salon.

Post Xenia High, he followed his father’s advice to attend

Jimmy sought out John Onye Lockard at a large Ann Arbor Street Festival having heard he'd be there. The two connected and Lockard, who would become his mentor, suggested that Jimmy

Amid rolls of Visqueen (polyethylene sheeting) and copious two-by-fours, they worked. “I rented a room from him. He had a studio on the loft level, and I had the studio below. You had to go thru my studio to get to his. We spent a lot of time together.” Lockard taught at both the University of Michigan and Washtenaw Community College. “So I would take his drawing classes at Washtenaw Community, and I also took his Introduction to African American Studies at U of M. He was a talker from Detroit—always verbal. He’d pick a subject and exhaust it," Jimmy says. "He had a great library. I learned a lot about black history and black culture from him.” On painting, he learned, “how to look at what’s working; what’s not working, how to think it through. I think I met him in ‘79-80." He recalls working on a mural paid for by Esther Gordy (Berry’s sister). Half of it was set in Africa with Shaka Zulu and half of it in African America. He did a series of washes over a figure of a drummer, to increase the richness of the colors, shadows and highlights. “I worked on that for three weeks. Washing it down, bringing it back up; Washing it down, bringing it back up and he looked at it in week three and said ‘That’s a good start.’ I’ll remember that line forever. But it looked good, and I learned a lot," he says. "He died last year.”

Jimmy with mentor John Onye Lockard, twenty-five years his senior. "I like this picture because I was at his elbow; his knowledge flowing into me." Photo courtesy of Jimmy James Greene.

While in Michigan, he met a single mom (of a young son) committed to being a writer. Her focus helped him to take his artistic practice seriously. Deeply in love, they married. When she was offered a scholarship to a Master’s program at Brown University, they made a move to Providence, Rhode Island. He'd acquired some life experience, so he thought that he too should return to school. He applied and was accepted into the prestigious Rhode Island School of Design, but he couldn’t afford the steep tuition. His wife encouraged him to seek financial aid, and he ended up with a full-ride. He’d already done the apprenticeship with Lockard and completed his electives, so he needed only to take studio courses. “I applied for advanced standing because I’d had some illustrations published and had done some art shows. And because I was married with a kid, I didn’t want to spend a lot of time. I wasn’t into the college experience of hanging out at the beer tap and all that. But I wasn’t taking care of business, and [at RISD] you can’t come in slacking.”

Halfway through the first quarter he got a jolt, a call from the Minority Affairs office saying he needed to step it up—he was failing. “I thought, I can do this, and I buckled down. By the end of that quarter, I made the Dean’s List. I got my BFA in two years with a 3.8 average. It was a lot of work!” He was impressed by the caliber of his fellow students. "If it wasn’t right, the

Christ dragging the cross through the cotton field taunted by the overseer’s lash was the first image to come to him as he began the series. A jubilant nativity scene created in stained glass became the pièce de résistance. Only the watercolor study of the triptych survives. Images courtesy of Jimmy James Greene.

Jimmy had painted "stained glass" images until he decided to learn to create the real thing. “So I took one of those Learning Annex

About a year after his RISD graduation, Jimmy and his wife (unnamed to respect her privacy) parted. He lived for a while with his brother, Paul, in Cleveland, then decided to visit sister Aicha (née Jan) who lived in Paris. One of his RISD instructors hooked him up with a sweet deal, five or six freelance textbook illustrations

He took in the

He created Flying Colors in 1998 for a designer show house at Madam CJ Walker's former home, Villa Lewaro, benefiting the United Negro College Fund. It draws inspiration from the room’s “jockey” theme.

Thinking ahead, he’d packed as much of his work—“mostly collages, flat stuff”— as he could carry on the transatlantic flight in hopes of selling them in the City of Lights. On his sister’s kitchen table, he created even more and the stars aligned. "I met two models with a fabulous apartment in the center of the city and did

Seduced by Washington’s 1970’s reputation as a “hot” black arts district, but accustomed to state-of-the-art facilities from his RISD experience, Jimmy was underwhelmed by the resources at Howard. “There was a room; that’s it. Here’s the key,” he says. He reiterates, however, that “the professors were great.” He earned a 4.0 his first semester, and that was it; so long, master's degree, hello New York.

New York and the 1990’s brought marriage to Sherri, the birth of their daughter, Loni, several art commissions, as well as the start of his long teaching career. His first stop was Brooklyn, where he connected with the oldest, continuously-run, black owned and operated gallery in New York City, Dorsey’s Art Gallery. He would participate in many group shows there alongside such artists as Otto Neals and Carl

Then and now: Jimmy and his beloved daughter, Loni. He and wife Sherri parted when Loni

In 1990, he became one of the artists on the faculty of Studio in a School. “It’s a great organization, taking professional artists and putting them in the school system. It was four days a week, with a nice budget and supplies up the wazoo.” His work with kids prepared him for a large commission from New York’s Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) in 1996. “They wanted children’s art involved in the project, so it felt like coming up with a lesson plan. I proposed to do workshops in community centers and projects around the station

Another public commission was for a mural in the Herbert Von King Park amphitheater in Bed-Stuy. He won the $10,000 open competition with the submission of three sketches.

The Children's Cathedral, by Jimmy James Greene and the children of Bed-Stuy. Fabricator, Peter Columbo. Photo: Metropolitan Transit Authority.

After twelve years with Studio in a School, he realized “there’s no pension; no stability,” and entered a program that helped artists with “seniority” transition into the Board of Education to teach in New York City public schools. However, a graduate degree was a prerequisite. “You’ll be invited to leave if you don’t get your master’s degree,” Jimmy laughs quoting the Board of Ed. So he began his master’s studies online but had to file for an extension when a ruptured cerebral aneurysm threatened his life and sidelined his plans.

On an unlucky Friday the 13th in February, he headed home from work to get ready to see a play with his girlfriend, writer Julia Chance. "I walked down Bond Street, stopped to get a newspaper, and I got this incredible headache at the back of my neck; and I don’t get headaches. I thought, oh wow, something’s going on." But he made it the couple of blocks to Julia's place, the apartment above his.

"He didn’t look well—pale and shaken," Julia says. I asked him if he wanted to go to the hospital." Since men often have the tendency to "tough it out," she knew it was serious when he said yes. As Jimmy began convulsing in the emergency room, she was sent out. "It was extremely scary," she says. When finally she was called back in, the doctor told her "there was some bleeding on his brain; he was very ill and could die. It was extremely scary. Then, in the same breath, he said to go talk to Jimmy to cheer him and keep his spirits up." He'd have to be transferred to a hospital that specialized in brain surgery. Coincidentally, his sister Judy, already

He would undergo coiling, a procedure to stanch the brain bleed. Jimmy remembers "the doctor saying something to make me laugh, and that's when I went out. The next thing I remember, I had tubes in me." He spoke wanly to Julia, saying, “Sorry for messing up your Valentine’s Day.” Julia had rallied the troops; friends and family hovered near, bearing not hearts and chocolates, but all the love and healing vibes we could muster. Jimmy has little recall of the details. “Judy tells me that the nurse asked if I could raise two fingers and I did—two middle fingers. So Judy said, 'Okay, he’s going to be alright.’

And he would be, but it was a long road. "There was cautious optimism in the days that followed," Julia says, "as there were some complications along the way. One of the things his family and I were concerned about

Jim et Jules. Jimmy with Julia Chance. Photo courtesy of Judy L. Greene. The artist stands before Quiet Intensity, (dry pastels on

According to the National Institutes of Health, “it is estimated that about 40% of individuals whose aneurysm has

“With teaching and everything else, it ended up taking six years to get my master’s," he says. "That final thesis? I went for it. It was an artistic interpretation of the last five plays of August Wilson’s Century Cycle.” He did collages for each decade: the Fifties (Fences), Sixties (Two Trains Running), Seventies (Jitney), Eighties (King Hedley), and Nineties (Radio Golf). “But I had to propose them in such a way that was more than just that,” he says, adding that he provided analysis of each play and a history of black culture for each decade. “So there was a lot of writing: the historical component, the review of August Wilson’s work and his biography. The artwork was almost an afterthought,” he says of his professors. “They’d say, ‘Oh, it’s nice,’ and then they would start talking about what was written. That was their expertise.” There was no cogent critique of the artwork. “It was always positive, 'looks good,’ but I never had to rework a piece.”

From August Wilson's Century Cycle: A Visual Representation, characters from the play, Fences, Troy Maxson and his son, Cory represent the 1950’s. (left) Masai Passages, acrylic on canvas, (right) was created during The Moving Form, Jimmy's live

Graduate degree secured, he had the credentials to teach in New York City Public Schools. “Rather than trying to find somebody who is really talented and fire them up,” his charge as an elementary school teacher is to “open up the idea of art-making; make it accessible and get kids to venture into the process.” He’s now taught long enough to see the trajectory of some former students into adulthood. “One, Peter Wright, has become an arts activist. I remember asking him what he wanted to be when he grows up and he said, ‘a movie director.’ He was always a very interesting kid.” Now known as Souleo, the multi-hyphenate Brown University grad is a DJ-Journalist-Curator-Producer.

Browsing an article on Matisse called “Material Witness,” which featured the materials used in his paintings, sparked an idea for Jimmy’s Adinkra series. “I thought that’s a great way to do some work, use your own possessions. I use three elements in each: a piece of African art that I own, an Adinkra symbol, and the meaning of the symbol. I didn’t do any sketching; I just came up with something directly onto the canvas.” He gestures to Sankofa, with a rendering of a prized statue, and an aerial view of a slave ship's human cargo.

From the Adinkra series, Sankofa (left) and Ubiquity (right) both, acrylic on canvas.

His favorite of the Adinkra series, with its analogous color scheme, features the most ubiquitous of Adinkra symbols, Gye Nyame, representing the omnipresence, omnipotence, and omniscience of God. He incorporates one of his "bought on 125th Street” masks from all angles: “the front, the back, the side; so it’s everywhere at the same time. That one is called Ubiquity. Roy Ayers was on my mind," he chuckles.

The title of his current series, People of Color, holds

With

Newly retired from the New York City Public School system, he’ll have more time to complete his work, but what drives it? “I think in pictures usually; I’m just wired that way. That’s why I create, it flows through me. It’s a way for me to communicate, to identify what’s important to me.” But he allows the work to dictate the journey. He once asked his late friend George Bass (poet, playwright, director, Brown University professor and Langston Hughes' literary executor) "George, are you walking the dog, or is the dog walking you?" The reply, "My dog is walking me." It stuck. “So I’ve learned to let my dog walk me," Jimmy says. "I let the dog lead the way. August Wilson did that; it sounds mystical. He’d get a line, and then he’d write the play to see what it was about.”

“My father took me to a career day for college students, and artist Willis "Bing" Davis was speaking. He said, ‘You should be a black artist, you’re the only one who can tell this story.’ It’s true; you can’t expect anyone else to tell your story.” He strives to tell the story in his work. "It’s not art for art’s sake. It should have some purpose beyond that to connect to people’s lives.”

As we discuss some of his processes, we speak of obsolescence. Much of Jimmy's older work is documented on 35mm slides, and he acknowledges that he needs to digitize them. Having just read an article on photographers who work in film, he recalled the era when he sold art supplies. "The film section was huge--a big yellow section where Kodak ruled the roost--it’s nonexistent now. Another one was Chartpak; the store made a ton of money off that. Prestype, rubbing off letters? Gone, gone.” Though I know him to enjoy the immediacy and reach of social media, as he shares his favorite things, it’s clear he still plants a Capricorn foot solidly in the analog world.

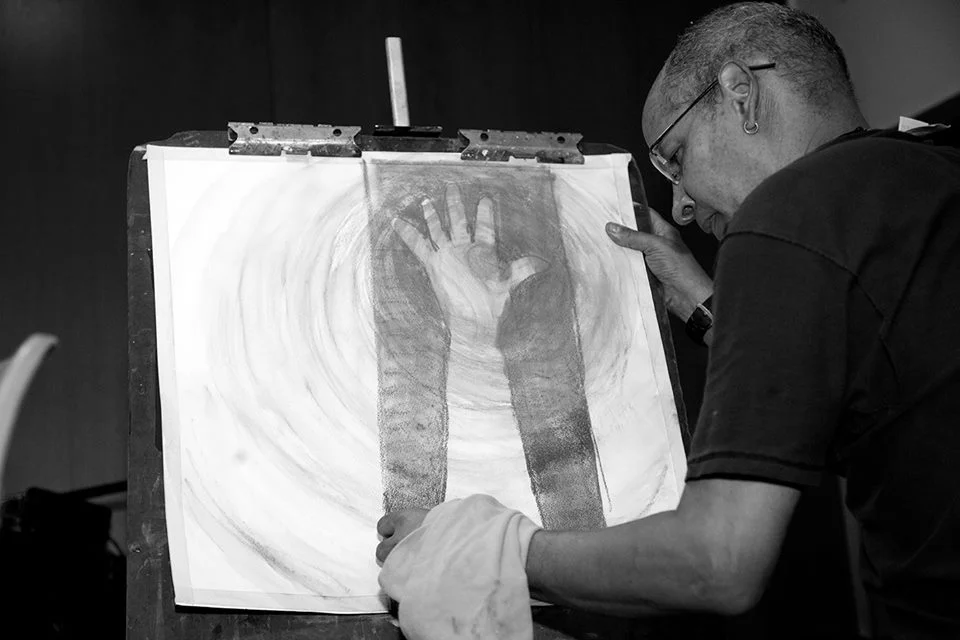

Jimmy James Greene at work, photographed by legendary creative director and artist, Hollis King.

Jimmy's TROVE:

1.

2. Pickett Proportional Scale No. 106C. A holdover from his student days in Rhode Island, "This is a wonderful little tool. If I want to enlarge something, there it is. It saves me; I don’t have to do math. Just dial up what I want. When I don’t have it, I miss it."

3. Logan 4000 Deluxe Handheld Mat Cutter. With its pivot-and-pull blade action and ergonomic knob for comfortable operation, the Logan 4000 is now one of the most advanced available, but Jimmy remains loyal to his trusty early version. "It’s just an easy, well-designed, simple tool."

3. Casio G-Shock Analog-Digital Watch. The best of both worlds, a rugged analog dial and an LED digital display in one sporty watch, it's a sentimental favorite. "It was a present from Loni; that’s what makes it special. Every time I look at the watch I think of her."

4. Fox-Hasse wooden professional drawing table. The 30" x 42" model originally designed as a drafting table has become a popular drawing table among artists. He got his in the late 1970's while selling art supplies in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

5. Fragrant Oils: Tunisian Patchouli & Almond Glow. The musky essence of Tunisian Patchouli floats in the air in his studio. It's his favorite scent. Kuumba Made fragrance oils are crafted of herbs grown on organic farms or wild harvested. He also enjoys the richly moisturizing oil, Almond Glow Body Lotion from Home Health Products, giving his skin a healthy sheen "without being greasy, " he says. And it seems to keep his Rosacea at bay.

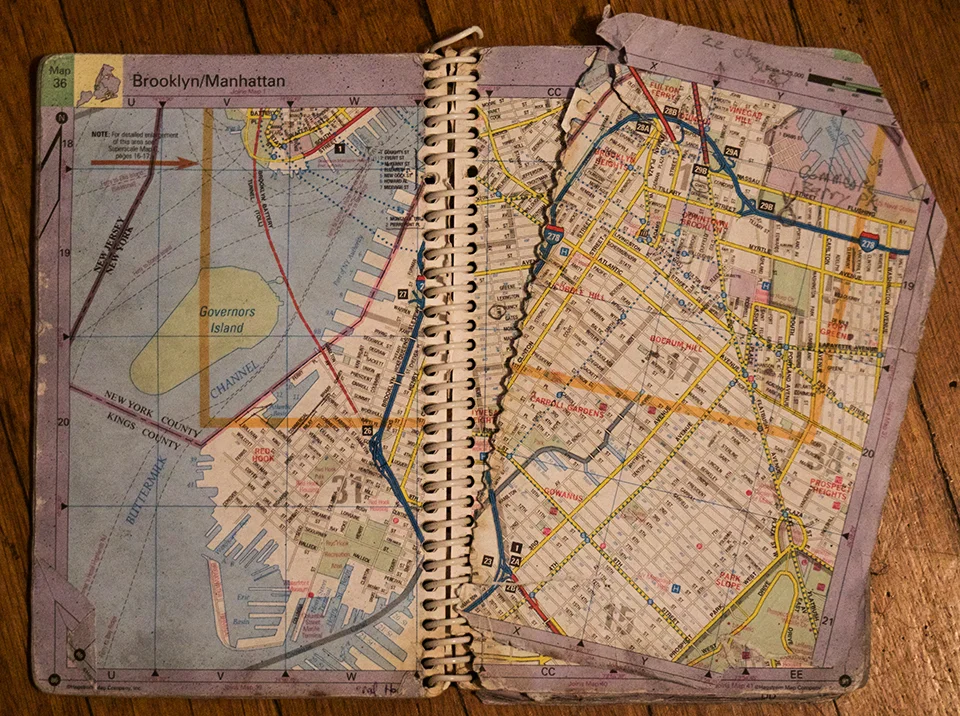

6. Hagstrom New York City 5-Borough Pocket Atlas. He relied on the red-jacketed Plan de Paris par Arrondissement during his stay in la

8. My African art collection. "My 125th Street Collection," he chuckles. "I never bought ‘em from a gallery. A lot of the bigger ones I traded. Wilkins Cumbo, had a trunk full of masks and stuff, he’d just come from a trip to Africa, so I exchanged my work for some." The figure above is "a Yoruba statue I don’t even remember where I got it, but I just like looking at it."

9. My Artley 18-0 flute. Along with his desk, "it’s one of the oldest things I have. I’ve had it since the early 80’s. I’ve kinda molded my lips and my fingers to it. So it feels very comfortable." And though he'd once bought a Gemeinhardt, "the Cadillac of flutes," interestingly, this Artley model (his favorite) is a student flute. "I thought I had creme of the crop, and I just got another ear of corn," he says dryly. "I’ve got a long history with that flute. It was from my playing days, back when I was a teenager and in my early twenties and was in bands and stuff." Bedecked in a subtly embroidered grand boubou and kufi, he beautifully soloed on his Artley at the beach wedding of this writer.

Photo courtesy of Jimmy James Greene.