“We held on to the core of being Southern in terms of niceties,” says Florida-born artist and educator Janathel Shaw of her family's migration to Washington, DC when she was six years old. Though she became a fast-speaking city girl, the vestiges of her Southernness show in her hospitality as she offers a thoughtful selection of beverages and healthy noshes upon my arrival for a private viewing of her solo exhibition, SOLIDAREity!

Drawing was Janathel's first medium in childhood, and to this day she puts pencil to paper, often in large graphite portraits. From left, her sister, Dorethea studies Here to Stay, ©2017 center, Prodigal Son, ©2015, a rendering of her son Maurice; a gallery patron stands before The Poet, ©2015.

Dorothy Mae Shaw named her first-born Janathel, a portmanteau of her husband James and mother Ethel's names. Daughter Dorethea would follow, then finally, Jay. Small town life was dramatically different than the urban lifestyle the family would take on with the move to the nation's capital. In flashes of memory, Janathel recalls Florida living: a languid pace, doors that were never locked, sitting on the porch with family, and instead of an ice cream truck, mango trucks that sold "juicy fruit bursting with flavor" at 25 cents a pop. “It was akin to the Black version of Mayberry,“ she says. She smiles as she speaks of her “deliciously country,” Aunt Evella. The one who “wasn’t sadity;” who had a black pig, an outhouse and ice-cold bottles of soda, "glass, of course," that she allowed the children to drink freely. Although she appreciates the quaint charms and sense of community in Fort Pierce, Janathel is much more inclined toward metropolitan living.

When her parents separated, her mother, a highly regarded teacher, found a teaching post in Washington, DC. Both Dorothy and her sister Carolyn made the move North, finding homes near each other. Janathel is grateful for their example as strong female role models. “My mother taught me the importance of resiliency—that women can do it. She kept us rooted in church," switching denominations from Baptist in Fort Pierce to Pentecostal in DC. “But she always chose small, storefront community-oriented churches. I think she wanted to recreate some of what she had in Florida." Attending Holy Commandment Church of God (Seventh Day), her mom eventually became "Mother of the Church." Janathel speaks admiringly of her mom and aunt 's efforts to instill values and cultural awareness in their children. "And education was a BIG thing." Very early in her church-going, education-oriented, woman-centered upbringing, Janathel learned to draw; loved it. She knew by the age of seven that she wanted to be an artist. She shared supplies with her Uncle Ray who did paintings on wood, and in truly iconic 1970’s fashion, on black velvet.

Janathel attended DC Public Schools, but never at a school where her mother taught. Mrs. Shaw did not want that pressure on her daughter. By the time Jan attended Hart Junior High School, she knew she “didn’t belong.” She hated it and the sexist course selections of the era. Though the school offered woodshop to boys, girls weren’t not allowed. “I had to take home economics,” she grumbles. “And I couldn’t care less about making the perfect pancake.” The boon in her experience there was meeting the teacher Mrs. Washington, “the Frances Cress Welsing of Hart Junior High. She was this authoritative, dignified black woman. You will speak articulately!" Janathel mimics. "She spoke about pride and integrity.” And it was upon her suggestion that Jan enrolled in theater class. But still, Janathel wanted out, and Duke Ellington School of the Arts seemed a perfect opportunity to find her arts tribe."

“In about 1975, I heard inklings about Western High School turning into Ellington for people who were going to pursue art. I begged my mother to let me audition. I don’t belong at this school,” [Hart JHS] she implored. “I don’t fit in. I’m not interested in being a cheerleader. If you try to get decent grades, you get picked on. I’m not into fighting, and they’re starting to have gang fights around here. I’m not interested in boys; I just want to go to school and be an artist.”

Her mother had wanted her to become a lawyer, but conceded to her wish, with her promise to maintain her 3.6 grade point average and just a bit relieved that she’d be attending school across town away from the possibly impending neighborhood chaos. “We didn’t have to duck and dodge bullets, though,” Janathel makes clear. "It was a hard-working community in the Anacostia area; mixed blue and white collar, but not wealthy."

“I was so desperate to get into the school,” she remembers. To increase her odds, she sought the opportunity to audition for both the theater and the visual art programs. Incredibly nervous, she forgot her lines for the theater audition, so the pressure was on to ace the visual art audition. "All excited and intimidated," she and her fellow artists-in-training were expected to draw sculptures set up on tables in the school cafeteria. They worked for four hours (with breaks as necessary) as the teachers circled the room observing them. "They wanted to see you complete a piece; be disciplined with it," Janathel remembers. "All I kept thinking was I’ve got to go to this school; there’s no other option. When I got the letter of acceptance, I jumped all over the place. I remember feeling this is where I belong, where I can be me.”

Elizabeth Catlett, Singing Head, 1980, black Mexican marble. Collection of Smithsonian American Art Museum, a work that deeply inspired the young visual art student. Senior portrait, Duke Ellington School of the Arts 1980 yearbook.

Commuting to Georgetown introduced her to another way of being; of attending a school where one could sit on the lawn. “It was Nirvana at the time, and I was so happy to be there.” Some of the instructors included working artists Billy Harris “in his Afro, bell-bottoms and platform shoes,” she chuckles. “He was all about art, it was not a game. Lilian Burwell

"Pearl Bailey came

And she speaks almost reverently of Ellington board member Peggy Cooper Cafritz, the avid art collector and philanthropist instrumental in bringing the school into existence. “I remember her coming to the school— short cropped

“Whenever she spoke to us it was always in a way to embrace us; we always felt important when she was there. I remember going to her house, she'd invited us to her home for a cookout, and we had free reign. It

Attending Duke Ellington set Janathel on her artist's journey. "I made some life choices that changed some of that— I became a parent early, but I think that without that introduction, I'm not sure what I would have done.“

With the many museums under the auspices of the Smithsonian Institution, DC was an excellent city in which to be an art student. She first encountered one of the singing heads by Elizabeth Catlett on a visit to the Smithsonian American Art Museum. "I didn't know that she was black. I saw the piece in the foyer and kept coming back to it, fascinated. I was just mesmerized.” It would be much later, while doing research for her thesis that she discovered the parallels in their lives: “She [Catlett] was from DC, raised by a single parent, educated in DC Public Schools. She was outspoken, headstrong, and created a diverse body of work. She was tall and gangly, a big girl like me with big hands. She spoke her mind through her art and I said, 'I want to be like this woman.' She was a role model. She surpassed expectations and was unafraid to tackle social critique through her art.” Jan is grateful to have met and spoken with the acclaimed artist before her passing and hopes that she can be a similar source of inspiration to a younger, burgeoning artist.”

"I had no idea of the

Upon graduation, she attended Howard University, but soon took time off after the birth of her son Maurice. Her mother had already laid the blueprint for beautifully raising children as a single parent. "I tried to raise my son with the same nurturing, commitment and dignity that I learned from my mother," she says. Eventually she went back to school, enrolling at Prince George’s Community College, where she worked as a graphic designer on campus and attained an Associate Degree. Her instructor, John Krumrein, had attended George Washington University’s (GWU) Columbian College and suggested she apply. He wrote her recommendation. She worked full time, paid a babysitter during days, and went to school at night. She is grateful for family support in caring for her son in the evenings. It was challenging. She frequently felt left out at faculty/student gatherings where she “would be in the middle of the room and no one would talk to me. There were some classes I couldn’t get into.” She remembers one British professor saying that he was welcoming the underprivileged to his class. As an educator today, she tries to prepare her students for the “

In spite of those struggles, she continued at GWU in pursuit of her MFA in Studio Art, Ceramic Art and History under the instruction of Turker Ozdogan. She, a Black Pentecostal Washingtonian enjoyed the diversity of her cohort: artists from Alaska, Bolivia, Canada, Japan, Pakistan, and Turkey; mostly women; mostly feminists and of varying spiritual faiths. One of the advantages of a diverse student body, she says, is that “they get to work things out to move beyond the mythical barriers that are set up.”

The grad student working on Sistah Anger from her ©1994 Sistah series. Photo by Andrew White. A work, cut and hollowed.

“Sometimes I would take Maurice with me to school and sometimes that didn't work out, but I wanted Maurice to know that his mother was an artist." Her giggling, toddler son would accompany her to art shows, and there were times when he painted over his mom’s work. So she created canvases just for him. “I said, 'Sweetie, you can't paint over Mommy's paintings,' and we'd paint together.” Young Moe became accustomed to his mother painting "in the wee hours of the morning or late at night. I wanted Maurice to understand what it was like for Mommy to have a dream and watch her try to pursue it."

She went through a prolific period in which she was exhibiting regularly and garnering attention for her sculpture in magazines and with NCECA, a national body of ceramic artists. “I was keeping my eye on this prize," and concurrently, "Maurice was dealing with being a young black male in this society. My family had to make me stop and realize I was somebody’s mother, because kids learn to say exactly what you want to hear. Thank goodness I had people around me who were saying ‘Jan, something's tugging at Maurice. You need to watch this.’ So for a minute, I put aside my pursuits to see what was going on with my kid, because it only takes a split second to make the wrong decision.”

Dubbed the "Murder Capital of the United States," 1990's Washington, DC was, at times, a frightening place to parent a young black boy. Vigilance was paramount. “I had to slow my roll a little bit to mother my son.” When Roger, who'd had a peripatetic presence in his son's life passed away, 15-year-old Maurice mourned deeply. Jan once dreamed of a particular measure of artistic success by the age of 35, but life, as it does, happened. With the passage of time and acquired wisdom, perhaps her oeuvre has been quietly incubating. “Maybe my art is taking on a level of

Hers is an art-filled home with works of her creation and those of other artists whose work speaks to her. “It gives me joy to wake up and see art on my walls.” In imagining her arts legacy, she hopes that her work will be acquired at the museum level and that her “voice as an artist, as a woman artist and a black artist” is heard, felt and understood. "I always see art as a legacy. Our time on this Earth is so short; I always think well what are you going to leave behind? The evidence of your existence besides existing in people's hearts is that which you have created. That's

She hoped to leave her artwork and the works of artists she's collected to her son. Sadly, Maurice—who shared his mother's eyes and smile–passed away in April 2015 at the age of 32, after quietly and bravely battling cancer.

Maurice Kewan Shaw. Jan's gentle, beloved Moe. May he rest in eternal peace.

Just months before his passing, Moe encouraged his mother as she was preparing a solo show. When he observed her lethargy he questioned authoritatively, "Don't you have a job to do? How many pieces do you need to have? What are you going to do about it? I said, 'Boy who you

Future Deferred, ©2015 I wanted to acknowledge the death of the young men who died like Jordan Davis, Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin and Tamir Rice, the little boy who was killed for playing with a toy gun." Using sgraffito

“I’ve said I have to actually discover who Janathel Shaw is. Part of that discovery did come forth when I was at GW; a lot of my work had to do with the black community. I had no idea that I’d carry that central theme throughout my work." What she did know is that abstraction is not her forte. "My work is representational," she says. "Though there’s not a genre that I can look at in general and not find something to admire. I love Greek sculpture; I love Vermeer, Rembrandt. I love Frida Kahlo."

With clay, she’s not interested in creating pottery though she admires the work of several potters. Her work bears “meaty” messaging; not idealized imaging. Though she can fully appreciate works crafted for aesthetic beauty, decorative themes do not drive her work. "When I create, my overall intent is not to make pretty art, but art that has meaning."

Janathel Shaw, Self Portrait, ©2012

Although she paints as well, it is her earthen works, ceramic figurative sculptures and reliefs that have garnered her the most acclaim. She became interested in 3-dimensional work as a student at Ellington, inspired by the work of instructors Stanley White (Ayokunle Odeleye) and Billy Harris, who "was welding and working

White/Odeleye left the faculty before she could take a class with him, but she was pleased when Martha Jackson (now Jarvis) joined the staff. "Martha introduced me to the ceramic medium. I touched the clay, and I connected with it," she says, remembering the resonant text from James Weldon Johnson's The Creation she'd recited

"I thought, I can create with this and I liked the idea that it came from the earth." She'd take the deep dive at Prince George's Community College (PGCC), taking classes in Ceramics, Painting, and Design. Because she'd had an illustration background, her early works were architectural clay slabs on which she drew, painted or glazed. She realized that her large slab formations were directly influenced by the work of Martha Jackson Jarvis, and sought to find her individual voice in the medium. "I went from making vessels to making figurative pieces. I had a good experience there." With an Associate's degree and Krumrein's encouragement, she went on to GWU. She "wasn't really knocked out by working with pottery," though she thought "working the wheel a good skill to learn." So she made "rudimentary forms and coil pots which are very satisfying." She references the "beautiful work of Maria Martinez, a very famous and humble Mexican artist working with the subtraction method"—using a carving tool to take away the excess clay to create the desired form.

She explains that though the ceramics medium is often relegated to craft—much to her chagrin— it is no lesser an art than those of the "major" arts. Working successfully in clay requires a delicate balance of aesthetic vision, artistic skill, an understanding of the properties inherent in different clay bodies, drying times, temperature and optimal

Janathel has never shied away from political art. Left, Still A N___/No Entry, ©2014 In her latest show, SOLIDAREity! she presents the powerful archival piece, because it remains as painfully relevant today as iit did when she created it as a grad student. Death God fo da Young'ns, ©1995 (installation) Ceramic with glaze, bullet casings, gravel and wood. She explains: "Death God grew out of my sorrow for the continued loss of young lives to violence, miseducation, misguided manhood rights and societal violence. The ceramic figure represents a deity that demands and feeds off the tragic deaths and unknown possibilities. The scarifications on the body are shown defiantly, and the visage of the figure is a distortion of what should have been a shaman or spiritual figure. At the base of the form lies bullet casings and empty shells of urban warfare. Some of the casings were actually found in a playground."

Timing played a part in her teaching career as well. She knew from growing up with an

She decided "I'm going to teach art, not a crafts class. I'm going to teach art in the way that I was taught at Duke Ellington." She set her limit at six years, with a plan to become the best teacher she could be. Her deadline came and went as she had "fallen in love with giving back. I got into teaching as a way of making a living, and along the way, I learned how to become an art educator. For me, it's not a formulaic lesson plan. I create my own lesson plans."

The teacher, working on theatrical set design with her DCPS students. Photo courtesy Janathel Shaw.

She once told a student to woo a girl with his understanding of art. One day she spied that student escorting a young woman around the National Gallery of Art. "I tried to hide so he wouldn’t see me while I heard him taking her through the exhibition. He was seducing

"If I’m not in the midst of creating or resting, I hit the streets to check out the art scenes here, in Baltimore, Philly and New York. I live in museums. I like studying the art at my leisure and I like surreptitiously staring at the faces of the visitors. Each face tells a story. I find the

Star Wars introduced one of the most favorite cinematic robot duos of all time: the

1. Moe's drawing of R2-D2 & C-3PO. A fan of the George Lucas franchise, she cherishes the image of the iconic Star Wars droid characters her beloved son created when he was nine years old.

Seated near African American sculptor Edmonia Lewis' famed 1876 sculpture, Death of Cleopatra, Janathel sketches the 1905 Elisabet Ney marble, Lady Macbeth at SAAM.

2. Drawing at Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) and National Gallery of Art (NGA). "My favorite spots are the third floor in the Modern Art section of SAAM and the quiet encased area of varied works near the Conservation Lab on the National Portrait Gallery side. It is routine for me to go upstairs, find a comfortable seat and draw marble sculptures for an hour or so to improve my drawing skills. I love to go the second floor of NGA in the west wing and draw the marble sculptures in the Dutch Galleries and on the lower levels that contain sculptures by Rodin. This extends to NGA’s Sculpture Garden which houses an ice rink during the winter and a large fountain during the summer months. The National Gallery of Art is the closest thing that Washington, DC has next to the Louvre. It’s not as intimidating because of the massive size or collection. I can go into familiar areas, sit, and ruminate. I also like it when I happened to visit on a day that a copyist is there recreating a painting in the collection."

Elizabeth Catlett at work on a bust. Dancing, 1990, Color lithograph. Target, 1970, Bronze.

3. Elizabeth Catlett. The late artist has been a role model for Jan's professional career. She is inspired by her proficiency in several mediums and her prolific output. "Her ability to just kill it with her master skills to create sculptures and prints that speak to the Black experience has wowed me for years." Seeing Target for the first time was like a "full-frontal punch," she says. "it was palpable." She writes about the piece in her MFA thesis.

4. Reading. "Books stimulate the psyche just as much art. I am a fan of Octavia Butler’s work, J. California Cooper, Nikki Giovanni, James Baldwin, Patricia Brigg’s sci-fi fantasy Mercy series, J.K.Rowling’s Harry Potter series, and Star Trek: Legacy series. I am drawn to characters that overcome adversity and create new realities for themselves."

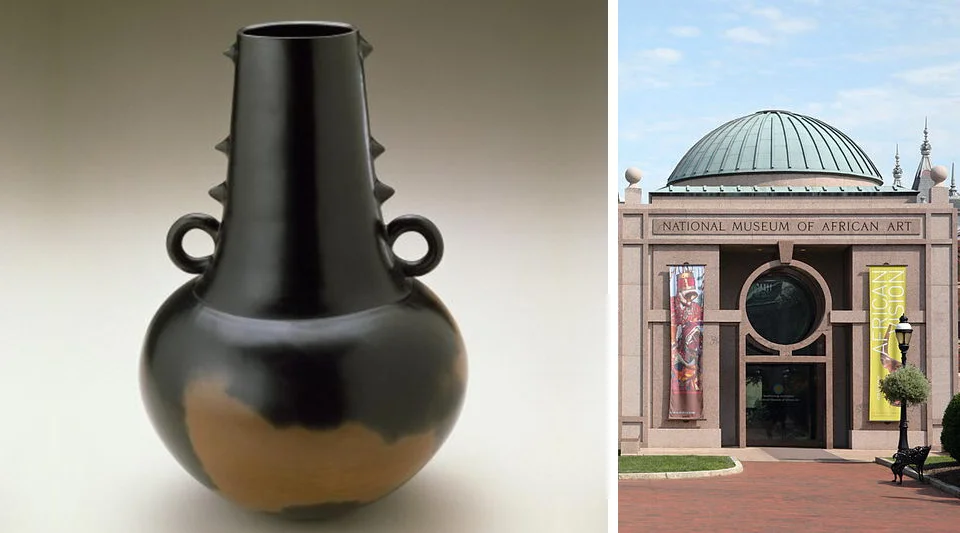

Magdalene Anyango N.

5. National Museum of African Art. "It reaches me on an intimate level and invites me to connect with my ancestry. I love the sculptures in the permanent collection especially the gorgeous ceramic vessels by Magdalene Odundo. I met her through a workshop coordinated by former Director of Education Veronike Jenke and artist, Winnie Owens-Hart. I felt a kinship with Ms. Odundo through our mutual love of ceramics. Here was an artist that wasn’t pretentious, she had some tools out, large coils of clay, wearing comfortable slacks and her hands were caked with clay. She talked about her method, background and creative process while creating one of the most perfectly symmetrical forms that I have ever seen. Each time that I see her work on display, I am in awe. It’s all about the form and the burnished surfaces. I marvel at the mastery that’s exhibited in the construction and the terra sigiliata that she creates to burnish her forms and that create varied natural hues after firing."

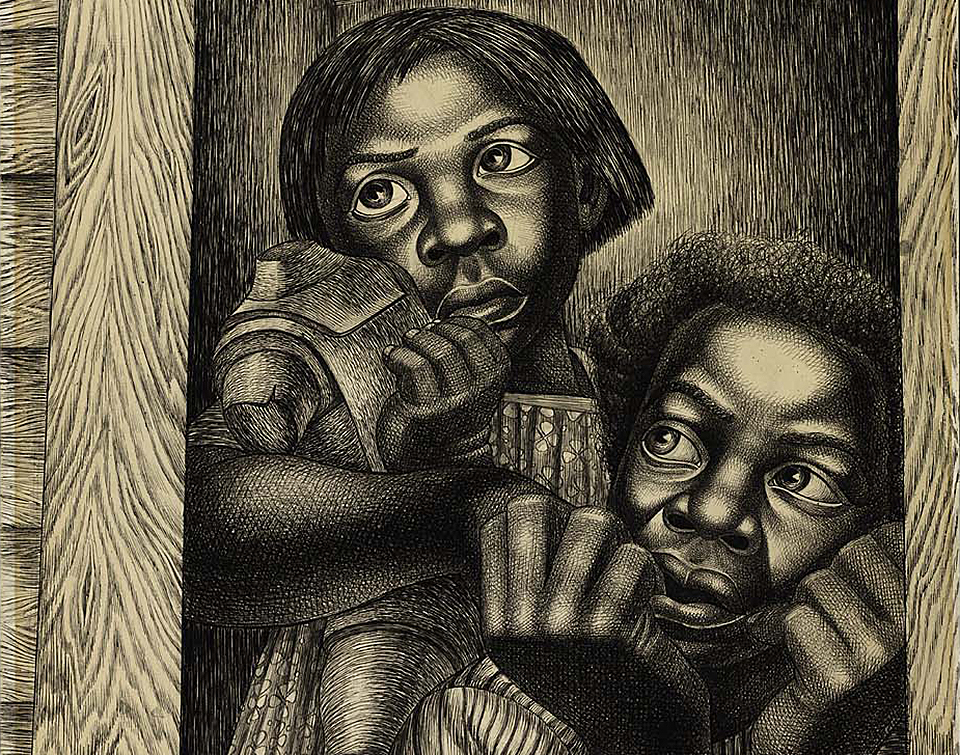

Detail from Charles White, Untitled, 1950, ink and graphite on paper. Collection of Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Julie Seitzman and museum purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment.

6. Charles White. "In respect to drawing, I love the work of Charles White. I know that he and Elizabeth Catlett had a volatile first marriage, but the man could draw. His portraits and figurative drawings have character, expressions that look right through you and his figures have meat on their bones. His women are not the stereotypical petite curvy figures. Their hands are broad, their features are strong with high cheekbones and piercing eyes. Love, love the contrast between light and dark and textures created from the layered lines. His contemporary John Biggers is just mind blowing awesome. These artists had a love and reverence for the Black community and history and the narratives are artfully shown in their masterful drawn marks."

View from the dock; Jan and Moe. The family gathers for dinner. Photos courtesy of Janathel Shaw.

7. National Harbor, MD. It holds treasured memories as a "go-to spot to have special family dinners with my son," she says. "There’s a serenity sitting in a restaurant or on the dock watching the sun rise or set by the water."

Left, Joseph H. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, designed by Gordon Bunshaft of SOM © Ezra Stoller | Esto.

8. Hirshhorn Museum. I expect to see one or two new exhibitions that show contemporary art that is in pace with what’s happening in the art world. The exhibits are varied but often, I am visually satiated. A favorite of mine in the permanent collection is Robert Arneson’s ceramic sculpture, General Nuke. Arneson’s manipulation of clay is magical and he was never afraid to explore social issues through his work." (General Nuke addresses nuclear weapons proliferation with the General's bust atop a blackened heap of bodies; his nose, a nuclear missile.) "Texture is necessary in his work. I love that he deliberately left his finger grooves in many of his pieces. It wasn’t the masculine aspect, but the artist mark that conveyed voice."

9. Her Story by Tim Okamura. Honored to have been immortalized by the master portraitist, she exclaims that this painting "will be one of my

10. Nancy Wilson. Janathel creates to music, "usually jazz or rhythm and blues. It speaks to how I’m feeling and it also creates a harmonious barrier from that which would distract me. What’s funny is that I’ll find myself creating to the tempo of the music," she says. What's in heavy rotation on her current playlists? The ever elegant, self-professed "song stylist," Miss Nancy Wilson.

Find Janathel Shaw on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and gallery-hopping the Eastern Seaboard.