Before the Central Branch of the Brooklyn Public Library ceded its premier address, One Grand Army Plaza (Its official address now reconfigured as Ten) to Richard Meier’s soon-to-come towering glass behemoth, Delissa Reynolds opened a neighborhood watering hole on a stretch of Underhill Avenue nearby. An idea born of the demonstrated need for local places to gather post-9/11, she planned to call it Tigerlily for the flame-colored perennial of her New Jersey upbringing. By her March 11, 2004 opening it had become Bar Sepia, brown, like her skin, burnished as is anyone's in a sepia-toned photo; all are one and all are welcome. In the thirteen years since, it's become a mainstay of the community.

Just blocks away from the bar, she extends her storied hospitality in her home, a spacious condo in one of the pre-war buildings lining Eastern Parkway. The farm table beckons with a generous bowl of fresh blueberries and other fruits, flaky croissants and muffins, jam-filled ramekins, delicate egg cups, and as her Grandma taught, proper linen napkins. Although she gets glam; does it well, she often rocks her roll-up-your-sleeves-and-get-it-done natural beauty. Hair pulled back, no makeup and wearing her casual “uniform” of denim work shirt–fitted and flattering her athletic body–she nonchalantly steams milk to a perfect froth. We settle in with our aromatic cappuccinos and she begins to tell her story of fits and starts, tenacity, resilience, and triumph.

Kindergartner Delissa; photographed at Bar Sepia by Elia Lyssy; rocking a signature tee; and photographed by Sergio Kurhajec for O, The Oprah Magazine, 2011.

Bellies sated and caffeine-fixed, we head to the living room, its mid-century furnishings stylishly inviting. On the wall, treasured photos and artwork document her life as well as that of her handsome husband, Elia. She identifies the beautiful brown folk featured in many of the images, each sharing her almond-shaped eyes. Descended from free people of color, their roots are in the tiny census-designated place, Cane Savannah in Sumter County, South Carolina. Gradual northern migration led them to New York City in the 1920's. Mary Louise Pitts made the trek north to study nursing. She landed first in Harlem and then, the Bronx, where she stayed with an aunt until marrying Curtis Wheeler, with whom she’d bear five children. Upon divorcing the philandering Curtis, Mary Louise, moved with their teenaged kids, for a new job as a private duty nurse and a new life in Monmouth County, New Jersey, where she’d marry again, twice.

Her daughter, Geneva would become a mother of three: Tina, Julius and the youngest, Delissa. Eventually fleeing an abusive husband, Geneva made the regrettable decision to leave her children. "She had to leave. I think she left to save her own life and I think it was a difficult decision for her to leave the three of us," Delissa says. Mary Louise raised her grandchildren with her third husband, James Reynolds, a pig farmer, on his family property in Middletown "on one of the few streets in Middletown township that had black people,” Delissa recalls. “It was pretty segregated and incredibly rural back then; our street wasn’t paved until 1972! But it was gorgeous, absolutely beautiful." This agrarian upbringing is the genesis of her love of fresh produce, cooking and the

Hard-working, industrious and generous, Mary Louise Reynolds (here with her grandchildren, Tina, Delissa and Julius) would eventually open the Reynolds Golden Age Day Care Center & Boarding Home for the elderly and mentally challenged.

While maintaining a peripatetic relationship with her children, Geneva tried modeling in Paris, where she briefly lived, then as actress "Gena" Wheeler, created a cosmopolitan life in New York City. She became the stand-in for a popular actress of the time, Barbara McNair. She appeared in television commercials and in three films: as a nurse in both John Cassavetes' Husbands and Arthur Hiller's The Hospital, and in “The Female Response,” like many black actresses of the era, as a call girl.

In the early 1970’s, only a few salons below Manhattan's 125th Street catered to African American hair care. Securing a $90,000 bank loan, Geneva made a bold business move, opening Le Zèbre Beauty Center at 30 West 57th Street in 1975—one of the first black women to open a midtown salon. Located between 5th and 6th Avenues near the highly successful Vidal Sassoon salon, it offered beauty and grooming services to men and women from model Beverly Johnson and flutist Bobbi Humphrey to NBA star Willis Reed and vibraphonist Milt Jackson. A July 1977 New York Times article, featured Gena—photo included—alongside top beauty mavens Adrien Arpel and Madeleine Mono. Though not the first to utilize défrisage, a hair straightening technique credited to Walter Fountaine of the West 23rd Street salon, Coif Camp, she held the trademark, filed August 16, 1976, for the deep-conditioning variation used at Le Zèbre.

Delissa recalls the “very, very chic” salon: “Le Zèbre was in white block letters. The front [of the salon] was all white with white leather seats. Zebra wallpaper in chocolate and silver. Dark carpets. Chrome benches with mushroom suede. My mother designed the hair dryers to come down out of the ceiling to the styling chairs. Just incredible! There was a big blowup of the Vogue cover with the zebra and she had a multicultural staff.” Just a tween when it opened, Delissa was wowed by it all.

Years later, as she headed to volunteer as a candy striper in Red Bank, NJ, Delissa stumbled on a copy of Celebrity magazine on the street. Coincidentally, as she picked it up, it fell open to an article on her mother and a revision of the Bronx-born beauty’s history, one that made no mention of three beautiful children, which stung, “But nobody would have believed she had kids our age," she says.

Gena Wheeler's headshot—Delissa's favorite pic of her mom; the movie poster for The Female Response, with ensemble billing; and a publicity still of "Victoria" in a scene from the film.

Delissa’s relationship to her mother was one of deep veneration intermingled with feelings of bafflement and loss. “Every child admires their mother, and my admiration was epic! Although she didn’t go to college, my mother taught herself to speak four languages: French, Spanish, German and Portuguese. She was intelligent. She had such presence. Her manners were impeccable—we were all brought up that way. She was absolutely stunning. She could stop traffic. And she knew that. She wasn’t afraid of that power. I admired that.” Of her design sense, Delissa continues, “Each home she had was immaculately furnished. She had a Mies Van Der Rohe suede sofa, Barcelona chairs, and high-gloss parquet floors. I mean, she had cable TV before people had cable TV!”

She rhapsodizes further: “She just had incredible style. Everything was tailored and her bags and shoes were fabulous. I was just enamored with her; she was so beautiful and she smelled like Rive Gauche and leather.” She closes her eyes, imagining the splendor. “She was the shit! She definitely influenced a lot of my stuff, even though I didn’t always like to admit it because she abandoned us,” Delissa says wistfully, but adds that she now sees that her mother was "talented and tenacious and resourceful. I think I come by those traits honestly and I appreciate that."

The dynamics of a difficult home life and being one of the few black students at Red Bank Catholic High School made for a troubled adolescence, but a bit of magic entered her life quite literally when she happened across Doug Keller's House of Magic. Keller, a magician, was at the time, hiring makeup artists for Halloween. “So I learned how to do prosthetics, really elaborate stuff,” she says. “I made a lot of money doing makeup.” And the entrepreneurial instinct kicked in. She also started therapy with Keller’s psychologist wife. Upon graduation, Delissa, enrolled in Brookdale Community College in Middletown, but like her sister before her, joined the Le Zèbre team part-time. She rented a "tiny room" at the all woman's Barbizon Hotel in Manhattan. "I was just grateful to have a roof over my head," she says. "I commuted to school in New Jersey, then worked at the salon as a receptionist on off-days." So began a years-long journey to find her voice and her footing; boomeranging from points elsewhere back to New Jersey.

While stationed as a First Lieutenant in Mannheim, Germany, a West Pointer she'd met through a cousin sent her a one-way ticket to join him. They married in a civil ceremony in Denmark. “I knew within a nanosecond that I’d made a big mistake, and so did he. I was 19 and he was a Republican," she says dryly. When her husband’s unit transferred out, he offered her the option to stay in Germany. “I really wanted to. I’d met such a good group of people. I worked in Heidelberg on the NATO compound for the University of Maryland in the Pell Grant division. My friends encouraged me to stay, but I thought I was supposed to stick by him." They moved to Junction City, Kansas and ultimately Fort Bliss, Texas where they divorced. “We were young; we both made mistakes. That was a rough time, but I did discover acting,” she reflects.

Living in El Paso, she tried her hand at a few things, like landscaping, but discovered "I was a really good waiter." She started acting on a dare. Always with a weighty tome from the library—Poe or Shakespeare—in tow she'd dine alone, reading. "People would be like She's over there reading fucking Edgar Allan Poe, that's like the low keys on the piano," she laughs. When a production of a Neil Simon play came to town, her boss dared her to audition. "So I walk in, and there’s a guy with a handlebar mustache, a top hat and a cape and all these people emoting. So I sit and wait my turn." She chuckles at her naivete. The director, Paul Hurt, asked if she'd prepared a monologue. Delissa replied, "What’s that? You give me something to do." So he suggested she recite the alphabet in three different emotions. "I did angry, angrier and really, really mad and I got the job," she laughs. "I had no problem memorizing the play. I trusted my instincts and I listened to a Cosby tape for timing on my yellow Sony Walkman. I went on stage and it was like I stood at the edge of the Grand Canyon and fell backward. I knew I was gonna be okay. When I 'woke up,' everyone was applauding," she remembers.

She returned east to New Jersey, but this time in Asbury Park, away from the maelstrom of home. Both of her siblings were having difficulties and an aging Mary Louise once again had three children left in her care—Tina's daughters and infant son. Delissa wanted to avoid the quagmire of self-medication; of Jersey life. Determined, she landed a position at a Jean Louis David salon in Manhattan and moved in with her Aunt Bernice in the Bronx.

The salon was located on Park Avenue South near the bar/restaurant Live Bait, where in 1986 she would meet one of the most influential people of her adult life, Marpessa Dawn Outlaw. From the first they became “attached at the hip,” she says. Marpessa, who lived on the Lower East Side, introduced her to the vibrant downtown arts scene of the late 1980's. “Our stomping grounds were La Jumelle, then Lucky Strike opened!”

Meanwhile, the New Jersey household was imploding, Delissa would get wind of the chaos from her nieces by phone. “My grandmother was doing her best, trying to raise my sister’s kids, but the situation was not good.” A caregiver was able to help her grandmother care for the baby boy, Raymond, but she couldn’t handle all of them as Mary Louise, Delissa would later learn, was “riddled with cancer.”

“The house was in shambles; that was hard because I grew up in a house that was pristine. We had no idea how sick my grandmother was.” The Division of Youth and Family Services (DYFS) threatened to remove her nieces from the home and place them into foster care. Marpessa tried to be a voice of reason and talk her unprepared, 26-year-old friend out of taking on the huge responsibility of rearing the two tweens. “But I brought those two young girls to the Bronx,” Delissa says. “DYFS gave me three days to make that decision. “We lived in my Aunt Bernie’s second bedroom on a fold-out bed.”

"They started my transformation." Monisha and Aja flank their Aunt "Lisa."

Then the salon transferred her from the Midtown shop to one in Queens, creating a brutal, two-hour commute to the Bronx. "Aunt Bernie would have a pan of water ready so I could soak my feet when I got home, sweet woman." Geneva's siblings, Juanita and Marvin were also supportive during the time. When she could afford an apartment of her own in Manhattan, Delissa moved with the girls "to 91st Street between 1st and 2nd [Avenues] because there was a Catholic school right across the street, Our Lady of Good Counsel." Regardless of proximity, the girls "were late every single day! I was only fourteen when Monisha was born. I was like an older sister, not a parent. I had NO skills. I always wanted my sister to be well enough to take care of her own kids, because I didn't feel that I was equipped to raise those girls and I felt guilty the whole time and even after. I had NO business taking those kids, I didn't know what I was doing and I felt that it was unfair to them and they suffered for it, even though I tried my best."

But she learned to navigate getting the girls the social services they needed, like Medicaid. “It was SO hard. But you know what? We did it. I taught them how to survive in New York. I give them so much credit, because they really rose to the occasion, honey.” As did you, I remind her. “Those girls changed my life. They made me,” she says.

Through Marpessa, a cultural critic for the Village Voice, she started meeting fascinating people from the worlds of art, music, theater and film. She wanted to stay close to the acting arena, but “I started doing all the behind-the-scenes production stuff because I was terrified. I didn’t tell anyone I was an actor.” Craft services, with her knack for food presentation, was a no-brainer. “I was painfully self-conscious. My ego and confidence so fragile, but Marpessa took me to task on that shit. Raising her hands high she shouts, “Delissaaaaa!” feigning Ms. Outlaw’s exasperation. “Actually, that was even before I used Delissa. I went by Lisa,” which was smaller.

As a representative for other people and projects, however, she was fearless. “I had no problem asking for things and I ended up working for the company that did all the communications for cognac in North America and we did the Cognac Film Festival. I sent Marpessa and David Thigpen (journalists, both) there." She smiles. "Then the shift started happening, I started learning a lot more, gaining confidence and building up a resume. Everything really turned around, though, when I left publicity.” She made the commitment to give acting a real go and like other struggling actors started working in restaurants.

Michael Weinstein of Ark Restaurants Corporation and Gena Wheeler had friends in common, so

Then came September 11, 2001. “The planes hit, and that changed everything. Acting dried up, I couldn’t get arrested. I lost my temp job at 111 Wall Street and was about to lose my apartment." Assistance organizations, Safe Horizons and Salvation Army were a godsend. "Those kind, kind, kind, people saved me. I don’t think I’ve ever experienced such a depth of kindness and tenderness as in New York during that time. So tender,” she reminisces. Until she got her next job, she spent most of her time "at the firehouse on St. John’s Place, (Engine 280/Ladder 132, which lost 7 firefighters at the World Trade Center) supporting them. "I’d go over there, cook, and spend time with those guys. She says in an exaggerated Brooklyn accent, “Oh yeah, you on

Celebrating her birthday with the brave firefighters of Engine 280/Ladder 132 in Brooklyn.

"The subcultures were really interesting after 9/11." Drawing converging air circles with her fingers she says, There were these circles, and at some point, everybody had been at my house.” She was the center of the Venn diagram. “It was a way to stay connected and human because New York was broken." Wanting to create a space to continue that spirit of connectedness, one evening while she and her friend Ukachi Arinzeh nursed a couple of Coronas as their dogs romped on Mount Prospect Park, she declared, "I'm going to open a bar."

The girls raised and off into their adult lives, Delissa could actually plan the “what’s next?” of her own life. “I truly believe that when you’re supposed to do something, the universe conspires for your success.” Her early enthusiasm was met with some naysaying and doubt, which furthered her resolve. By then, she knew "a lot of people in the restaurant business. Clearly I had resources. I just thought, ‘Why not?’ The museum [Brooklyn Museum] was undergoing renovation, and 3.1 million people came to the park, museum and botanical gardens back then. It all made sense. And I knew maybe 5% of the neighborhood. So I wrote the business plan while temping at Citibank. I worked for the head of global securities, Simon Collier, what a good man. I was brazen. I’d walk into his office, sit on the back of his sofa, and say ‘five minutes, Simon, five minutes, that’s all I want, so what do you think?’ And he’d get so excited like ooh we're talking about our bar. Everyone at Citibank was awesome, I have to say. I temped all over Citibank. Uptown, Downtown, Wall Street, Franklin, Park Avenue…they hunted me down, is Delissa free? I had a ball.” But did she get money from them? “No, and I knew not to ask. I didn’t go to Chase and I didn’t go to Citi. I wrote the business plan and took it to Michael Weinstein, who said this is good I’ll do the projections for you. I took it to SCORE (a small business mentoring/education organization) and the retired business people punched holes in it, but I was like I wanna make this work. I want to learn what’s wrong so I can make it right.” And she, like her mother nearly thirty years earlier, walked in and boldly convinced a bank that hers was a viable dream.

Her December 10, 2013, Facebook post tells the story :

In August 2003 with business plan in hand and waves of encouragement from friends, a new boyfriend, neighbors and family, I approached Community Capital Bank with an idea to open a bar in, then a lesser known, but well-loved area of Brooklyn called Prospect Heights. The first bank officer (a small man with a dangerous idea of power) looked at me, down at my plan, back at me and with a smirk, sent me packing. This rejection set me on fire. I went back home, called the bank and asked for the Vice President who remarkably took my call. I asked him to just give me 5 minutes of his time and if, after said 5 minutes, I couldn't convince him of my idea, I would walk away. He called my neighbor, a mutual acquaintance and reference to see if I was reputable, then called me back to set up a meeting. Although terrified I was never more convinced that this idea would work. I arrived, he shook my hand, and he invited me in and actually took the time to read my business plan. Afterwards he called in the VP of Underwriting for the SBA who also read my plan. They both leaned back with arms folded and said, “Ok, you’ve got 10 minutes…” And brother, I used that 10 minutes like nobody’s business.

Long story short, at the end of the meeting, the SBA VP looked at me, down at my plan, then back at me and said, “I think we can do this. You’ll have to jump through some hoops, but I think we can do this”. He was right. I had to do back flips through those damn hoops but the loan was approved and Bar Sepia was born.

Today is the last payment on that mortgage.

Those of you who own a small business, a true small business, know that it isn’t easy. It takes passion, courage, hard work, encouragement, boatloads of money and a great deal of faith but most of all folks that see and believe in your vision. Community Capital Bank (once the largest minority lender on the East Coast, now defunct, absorbed by a larger bank like many other small lenders during the banking debacle and financial crisis) saw that vision and gave me a chance. I thank you, Harry Wells, my neighbor who vouched for me, John Tear, VP of Small Business Lending at Community Capital Bank and Francis Byrd SBA VP of Underwriting for seeing, believing and financing my dream. I kept my word and that debt is paid. Equally important, I thank you all who have supported Bar Sepia since day one. It wouldn’t have been possible without you.

Bar Sepia.

When asked by the underwriter about collateral, Delissa replied she was buying her apartment. “The building was just in discussion about going condo, so I decided I needed to do whatever possible to make that happen. I'd lowered my debt and my credit was in good shape. I basically begged, borrowed, and stole the down payment. This was around the time I met Elia. I told him ‘Look, this is what I’m doing and you can buy a ticket for the train or I’m gonna leave you at the station.’ And he was like ‘Ok, and this is what I do. Don’t ever get in the way of my work.’ I was like ‘bet.’”

So she bought the apartment in June and went back to Community Capital Bank. “I went to all my friends and asked for money to put into my account, I said ‘I won’t touch it, I just need it to be in there so they can see I have enough for six months.’ We started construction in November 2003. It took about two years to finalize the lease. I was paying the rent and the mortgage. Thank God Elia was working! It was hard. I don’t know how we managed to pay that mortgage off but we did.”

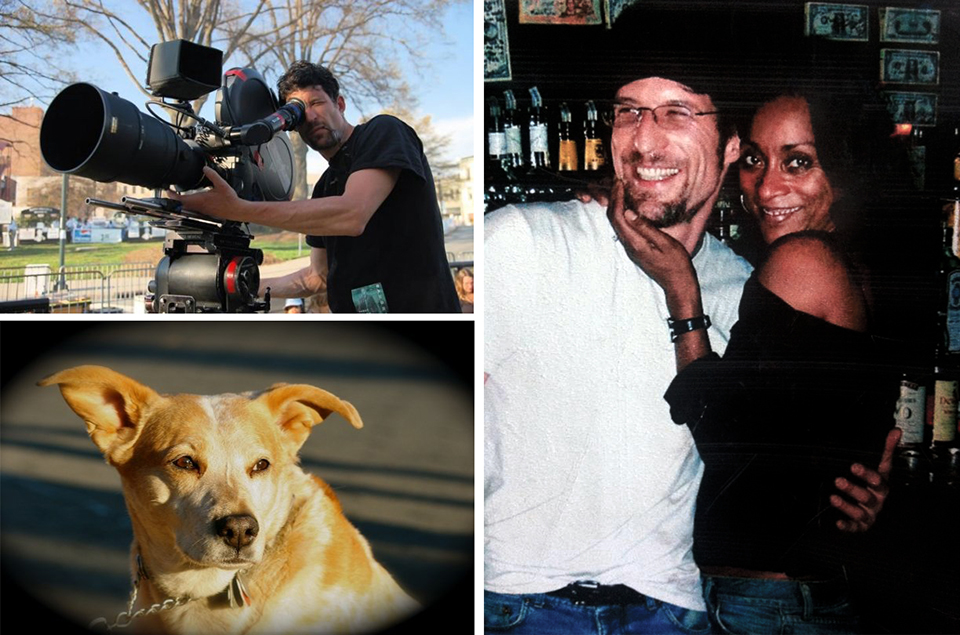

Elia at work; sweet Kika (Rest in Peace) and the grand couple of Bar Sepia.

Elia. At a holiday party in the home of friends in Hell’s Kitchen on December 2, 2002, Delissa met Elia Lyssy, a Swiss cinematographer as kind-hearted as is she. They talked and exchanged numbers. A week later, one of her Citibank colleagues asked her to cater a Christmas party at his home. “I invited Elia to come since it was in his neighborhood. We ended up sitting out in the hallway on the stairs with a bottle of wine

And the bride wore vintage. The stunning bride and groom surrounded by love: Aunt Bernice and Uncle Malloy.

It too seems not so long ago that Marpessa, who’d moved to California and valiantly battled an aggressive breast cancer, breezed into town post-chemotherapy, and held sway over an evening at one of Delissa’s legendary Sunday dinners in her home. An ever-gracious host, Delissa made sure that each of us in attendance was sated with food and drink before sitting down to bask in the smart, witty glory of her girl, who has since joined the ancestors. There is something deeply satisfying about the fact that the names of these two charismatic sisterfriends are bound together for posterity in the pages of Paul Beatty's National Book Critics Circle Award and Man Booker Prize-winning novel, The Sellout. A hundred or so pages in, driving the #125 westbound bus to El Segundo, we meet the character, "Marpessa Delissa Dawson."

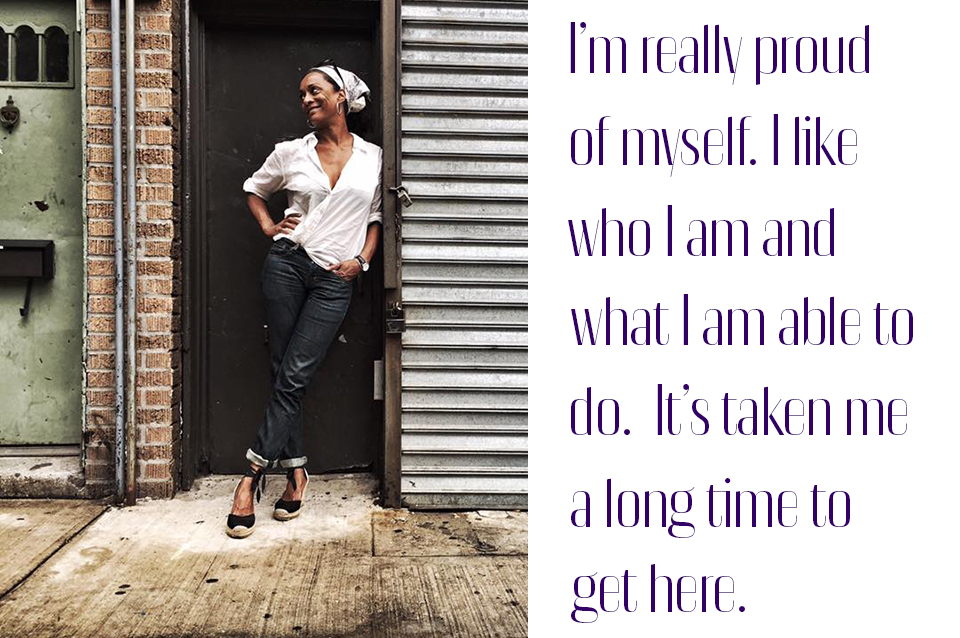

Photo: Tonchi Antunovich Finkin

By dint of her indomitable will, and she adds, “intensive therapy,” Delissa has moved beyond the early sense of abandonment that threatened her self-esteem. “I operated with a facade for so many years; it was how I survived. It was easier to have this image of fearlessness, then go home and get into the fetal position. I felt like a fraud.” She is today, thriving and grateful. "I love me. I’m really proud of myself. I like who I am and what I am able to do. It's taken me a long time to get here.”

The matriarch, Mary Louise has passed on. Geneva, Delissa is happy to report, is present and availing herself. Monisha and Aja, now adults, are well and raising families of their own and Raymond became an employee of Bar Sepia. Tina, who bore four more children through traumatic times, has since her release from Bedford Hills Correctional Facility, gotten a Master of Social Work and co-founded an advocacy organization for incarcerated and formerly incarcerated women, WORTH (Women on the Rise Telling HerStory). Delissa is very proud of her sister's resilience and commitment to empower other women. Julius has struggled, but his sisters and mother "have come together in a remarkable way" to help him upon his recent release from jail. She is touched by her family members' humility and concerted efforts to reconcile and rally for one another.

"My nieces and nephews are amazing human beings and are beautiful people all around" Delissa says. "I'm very close to them and very proud of them." From left, Aja Cathcart, Davion Reynolds, Kai Reynolds, Monisha Knight, Raymond Jackson and in front, Danielle Jackson. (Not pictured, Shaun Burgess)

Bar Sepia is now a teenager, and profitable. It has from its inception, fostered a sense of community with its many communal experiences. From Tuesday trivia nights and First Saturdays at Brooklyn Museum after-parties to Sunday dinners with such

Sepia Life: Delissa at the annual crawfish boil.

Annual celebrations include New Year’s Eve, Mardi Gras, Oscar Night, World Cup Soccer, Summer Crawfish Boil, Kentucky Derby, Halloween Costume Contest and the Tree Trimming

Halloween at Bar Sepia. Delissa and Elia with photographer, Gigi Stoll.

In the early aughts, inspired by her sister's experiences in the carceral system, she worked tirelessly with S. Epatha Merkerson (whom she met on Law & Order) on an annual fund-raising production to benefit the now-defunct Justice Works Community, an advocacy group for incarcerated women. Her business acumen and community-building orientation have garnered her several accolades: In 2005, she received the inaugural grant of Eileen Fisher’s Women in Business Initiative. In 2013, she won the Brooklyn Small Business of the Year award and was named to Brooklyn’s Extraordinary Women of 2013 by District Attorney Charles J. Hynes. In 2014, the Eileen Fisher company honored her again with her selection to 30 Women Entrepreneurs Changing the World in Take Part: Women In Business Initiative

(Left) Producers, Natasha Ferguson, S.Epatha Merkerson, and Delissa at at Justice Works benefit reception in 2005. Photo: Jamie McCarthy/Getty Images (Right) Errol Cockfield, Delissa and Andrea Bell at the Mayor Bloomberg Small Business Award Ceremony in 2013.

She’s resumed her acting career again. “I love the bar, but I felt very removed from acting, which was my first love. So if it means starting from scratch, that’s absolutely fine, I’m putting myself in the most vulnerable place again. I’ve been doing readings like crazy and working with Paul Calderón and David Zayas' theatre company, Primitive Grace, for the past two years. It’s an absolute blessing to be able to work with all these folks," she says. “I’m also back at the Actor’s Studio which is awesome. I’m stretching my muscles.” She's had back-to-back performances this year in Our Lady of 121st Street, written by Stephen Adly Guirgis and directed by Estelle Parsons, Actor's Studio Associate Artistic Director, and most recently in The Last Days of Judas Iscariot, also written by Guirgis and directed by Academy Award-winner, Parsons at LaMama. “I’ve really committed a great deal of time working on my craft and expanding my instrument as an actor and artist. I never really gave myself full permission to do this work and it feels great to come back to learn and grow with such an amazing community of actors. I’m thrilled and honored,” she enthuses. She's grateful for these mentors. "They are honest and encouraging. Kicking and screaming they pulled me by the hair and threw me into the deep end. Without Paul Calderón, Maggie Low and Estelle Parsons, I wouldn't be doing this right now. Estelle is amazing! She has no filter, and she's one of the best actresses in the world. And she knows it. She knows where there's value and she's not going to suffer fools. She's not going to waste any time on anybody she doesn't believe in. What she's done for me, I can't tell you."

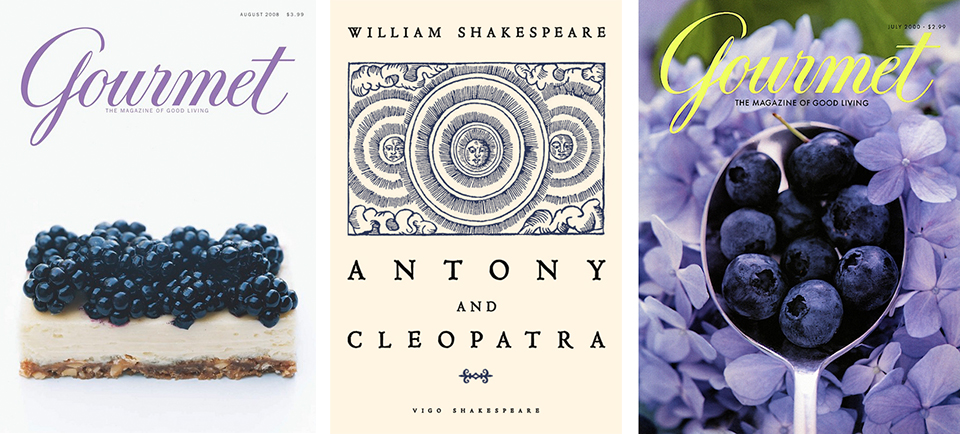

Delissa admires her activism (Parsons is the creator of The Actor's Studio Theater and Social Justice program) and stamina, "She's non-stop and she'll be ninety in November!" As Ms. Parsons gears up to produce some of the classics with non-traditional casting, she's advised Delissa to work on Antony and Cleopatra. "I'm excited about that," she says.

As Saint Monica with Judas (portrayed by Gabriel Furman) in Last Days of Judas Iscariot. Photo: LaMama Experimental Theatre Club

A woman of few words, Mary Louise Pitts Wheeler

Mary Louise Reynolds; Elia Lyssy as a small boy; a sketch of Elia, the cinematographer by none other than Tony Bennett; a sepia-toned treasure, the family's old New Jersey homestead (a wedding gift from Delissa's Uncle Marvin)

1. Family photos and memorabilia. Cherished pictures line a living room wall ledge.

2. A

Cherished ephemera.

3. Girlz Talk. An August 1991 article, penned by Marpessa for the Village Voice, shares the trio of Marpessa, Delissa and Donna’s outrage over the paucity of coverage for women filmmakers in a New York Times Magazine cover article on Black filmmakers. The article, yellowed with time, is framed and mounted in Delissa’s office above the bar.

4. Delissa's Shopping List, 27 Aout 97, Ramatuelle, France. Framed in the kitchen of her country home and painted by a grateful friend, is a list of ingredients for a barbecue meal Delissa prepared in Ramatuelle, France in August 1997.

5. Her Bookshelves. Whether her country home, city apartment, or Bar Sepia office, they're packed with plays, cookbooks, copies of Gourmet magazine dating back to the eighties, and sundry treasures.

One wall, hung with framed photographs of friends, Jerry Gonzalez, Todd Johnson, Marpessa Dawn Outlaw and Sekou Sundiata provides ancestral creative inspiration.

6. Memorial Corner. She's dedicated a corner of her office, to the memories of her dearly departed. As life cycles and loved

A vintage-inspired pretty from BHLDN.

7. Shoes. A love she attributes to her stylish grandmother, she collects vintage shoes of various eras from the 1980's on back, but she loves a fab shoe of any era.

The perfect country home a deux. Summer 2017 in East Meredith, Delissa and the doggie. Photo: Elia Lyssy

8. Her Country House. Way upstate in the Delaware County town of East Meredith, she and Elia retreat to their quaint, two-story house on a bucolic plot of land with a charming red barn fronting a small lake. It’s a long drive from Brooklyn, but a lovely getaway.

Bruce Springsteen and the Girls, Red Bank, NJ, 1979 © David Gahr

9. Photo of Bruce Springsteen & the cross country track team. The best part of her years at predominately white Red Bank Catholic High School

10. Her preparedness pack. Prepared for calamity she has, “every survivalist item you can imagine, including condiments and a coffee pot in this. Can you imagine me running with all this and the dog, like Where’s the bus? I’ve got rain gear; I have maps; I have an emergency radio. I’m totally outfitted for camping: gazebo, cots, tables, chairs.”