David Cea, Self-portrait, 2017. ©David Cea/dac photos

On a quiet, weekday morning with his lovely wife Lucy gone to work and their delightful daughters, Lulu and Nissa off at school, photographer David Cea grinds aromatic beans in a cherished old coffee mill. I tell him that the Japanese Maple fronting his home, next door to the house in which I was raised was but a mere shrub during my childhood and that seeing his girls, aged nine and six, offers a nostalgic look back to when my sister and I, also born three years apart, too picked dandelions and chased fireflies across the lawn. Eastern light filters through salvaged muntin windows into the dining room where we sit, drinking the café from hand-thrown ceramic cups as he tells of growing up during the Salvadoran Civil War, finding lasting love and purpose in his youth and the challenges of creating art, community, and life in the United States.

Born in 1978 on the precipice of civil war in the Republic of El Salvador, David (pronounced Dah-VEED) grew up in its capital city, San Salvador. Thinking of the world as a place at war because it was all he’d ever known, he “got used to it," he says. "I thought that was real life.” The youngest of four children, he “used to play war, and talk about war, and make [toy] guns. Yeah, we were always playing violent games— it was fun for us. And at the same time we were being fed with a lot of TV from the United States and that was a part of the problem. The war and also the TV showing us programs about war," he says. It is hard to imagine a violent streak as the man who sits before me radiates peace and goodwill. He adds that, "in general, I think my childhood was very fun, in the woods always playing free. No adults around.” Yet, he continues, it was “very communal, being raised by more people than just your dad or mom.”

Brothers Gustavo, Hugo and little David, cousin Daniel and sister Evelyn. Photo courtesy of David Cea.

His father was an engineer for the National Electric Energy Company; his mother, a homemaker with a strong entrepreneurial bent. She bred Schnauzers and French Poodles and refurbished vintage furniture. “She was always looking for deals; fixing a little bit the furniture,” he says. Today his home is filled with treasures discarded by others and tweaked into new purpose. Welcoming "life as is," he, through his photographs, illuminates magic in the minutia and the mundane--a bit of skin peeking through an undarned sock; a child's silhouetted bed leap, distilling each ordinary moment into an extraordinary thing of beauty.

Photo ©David Cea/dac photos

David's different way of seeing and interacting in the world conflicted with the regimented, linear nature of his schooling. "School was not a great place for me," he recalls. "I think I was always creating my own learning process—I learned a lot by myself. That's what I found out about me; that I'm hard to be taught. It's hard for me to put attention to a class for longer than two minutes," he laughs. "Well, maybe 20 minutes or so." His mind would wander to the myriad possibilities of creation. Or he'd interject with questions; which weren't always welcomed. "I question everything. Then I try to find out the answer inside of me." By third or fourth grade, he "started having big trouble in school. And it’s hard, you know, as a kid when you are more artistic and free," he says. "It was a nightmare for me being in school, everything was so militaristic. I know I was not easy," he allows. "I was more violent with life; with myself. School tells you, ‘you’re no good.’ Your parents tell you, 'you’re no good.' Then you start believing you’re no good. Your whole identity starts to get lost in all that struggle." He rejects a single-pronged approach to teaching and learning. "In that system, there are people who do really well and that’s okay, but it’s not for everyone."

He was the lone artist in the family “and because I was the youngest, my parents were tired and were busy,” he laughs. “But that was good because I feel I am very independent. I can create my own world, my own system without needing too many external things, so that’s something positive about being the youngest. I was in the street for lots of hours and they were saying ‘Where’s David?’ I’d come home very late; I was always playing in the streets. Then when I was getting older, I was getting kicked out of different schools--like three in one year. I was, (he searches for the word) very hardcore. I was doing really bad things when I was between twelve and fifteen, I was very naughty."

A page from the photo album: teenagers David and Lucy. Courtesy of David Cea.

And then he met Lucila Margarita Trejo. "Lucy came from New York to El Salvador after the war. Her family was trying to make a life again in El Salvador after being here [in the U.S.] for a long time. She was just very attractive as a person. She was different, maybe because she was coming from New York, with other views about everything. I kinda liked that. We hung out a lot." They became very close, but high school was still problematic for him with "big troubles: drugs, fights, guns, but not gangs." He became involved with the punk scene, listening to Misfits and Pennywise and joining a band himself. At about age seventeen, he and Lucy started dating. "We were really in love after being two years best friends. When I was dating her, I left all my friends and had a change. It brought me peace and set me with my feet on the ground." Then the Trejo's took their daughter back to the US. David was crushed. "I was eighteen, nineteen. I was depressed; I didn’t want to see anyone."

"When Lucy was in the States we were writing letters every day almost. There were no emails, it was paper. Love letters." Photo ©David Cea/dac photos

"Some friends started inviting me to play fùtbol." He took note of the changes that seemed to be happening in the lives of some of these friends— people he'd known to have "done bad in their lives." They began inviting David to join their Bible study group, but he was "

"

Danza Con El Sol. (Lucy) ©David Cea/

Lucy and David married in 2000. "We were young, twenty-two," he says. "We found that we were a team and we found that we were stronger together. That was true. Something happened when we decided to join together more formally. When we made the commitment, something became more powerful around us. It gave us more of an authority for life and to do things together. We were married for seven years without kids and that was a good thing. It let us do things: have fun, but also build, create, help." Finally, they thought, "Okay, now it’s time, let’s have babies." As a Permanent Resident of the U.S., Lucy needed to travel every six months, which wasn't problematic until it was. Having kids changes things. "I was out of the house a lot of the time. As a leader, I was very active. At the same time, I had my full-time job working with ex-gang members for another organization. It was very heavy, I was tired." Lucy suggested they relocate to the States. Initially resistant to the move, David finally acquiesced because the six-month travel intervals were getting to be a bit much, his mother had passed away from breast cancer the year before, and they decided to be close to Lucy's family in Washington, DC. "It was a hard process, leaving all our people there in El Salvador: all our friends, our community, and coming here as an immigrant. Then I thought, it will be sad because I am leaving, but it will be cool." The

"We were in a little apartment. It was very hard at first as an undocumented immigrant. They told me it will be just two years and then you will have your documents, but then they said six years. I couldn’t have a driver’s license. I rode my bike with my daughter to school, to play dates," riding through winter and hot summers. He stayed at home with then-toddler Nissa and launched dac+photos, with the mantra, "Life is beautiful. Let's make photographs!" Sometimes he'd bike to his gigs, equipment in tow, downpours be damned. He persevered, but admits his mind was "poisoned" with a voice telling him You’re not welcome here. The immigrant experience is often one of a persistent "fear hanging over," he says. "Suddenly I felt like I became no one. Lucy was saying, 'let’s go back,' but I said 'we are going to face this, let’s walk through this."

"Peace Be With You," hangs in front of Casa Cea. On the opposite side of the sign is Bienvenidos ("Welcome") ©David Cea/

"I started looking again for my connection to God. I said, 'I came here for a reason. It’s going to be okay.' Back in my country, I was someone; I came here and now I’m no one. I thought, this is good. Sometimes we need to go to a place where we are no one. I realized that it was a plan to build more inside of me. To be reconstructed inside." To find his true identity, not societal trappings of success. "My message in El Salvador was this: Who you are is what’s left when all your victories and all your failures are removed."

He found himself needing to heed his own messaging to adjust to and shape his new reality. He had to slough off feelings of "institutional and social rejection. After the third year here, I had an awakening. I started thinking about how the earth belongs to all of us and we are welcome to life. So I started thinking even the people who are born here and think this is their country need to be welcome to life, not to a country." He decided to "be welcoming to the people who live here and say 'you’re welcome to life; you are welcome to me; you are loved.' Even if they are against us or against immigrants or they are racist people, they need to find out they are not who they think they are. When they find out who they really are, they can treat others without labels too."

David and Lucy would find a house in a quiet DC neighborhood in which to raise the girls. With time he has become more rooted in the nation's capital. "This is where I live. It's a change that came from the inside out that was a product of being in a vulnerable process I call naked. It’s good to be vulnerable. You can hear more from your spirit. I started to feel much better. I realize the system pushes you to work, work, work, but then your kids have less of you. We decided to have less money but more life; more time to enjoy our daughters."

©David Cea/dac photos

"That's why I started my business as photographer here. I love photography. Since I was a kid, I was imaginative. I’ve always been very visual. I can’t remember notes, but I can remember visions. Every detail in a place I will remember. I love that; capturing a half-second of life that represents something really big. I started at fourteen, self-taught because there are no photography schools in El Salvador." He studied communications and graphic design.

"I had a graphic design business in El Salvador for 2-3 years and worked at an agency for another 2 years before I started working for an NGO from the US. It was good, I love to be in the countryside. I was a coordinator for the different projects in the mountains and rural areas, worked with ex-gang members." At the same time, I worked with our community of spirituality. But when I came here, I said ‘okay, I don’t have my documents; I want to be close to my daughters; I don’t want to be away from home for long hours; I’m going to start my business as a photographer." Because of his non-profit experience, he has been offered a consultancy with DC-based Equitable Food Initiative, "working with farm workers to certify their farms for fair conditions, better food, and safety." it requires some travel, but he's never away from his beloved Lucy and the girls for long.

Family outing in nature. ©David Cea/

"I was always a dreamer. In El Salvador, I was dreaming for big changes and trying to make those changes. I give all I have, my time, sometimes my belongings, what I make and everything to bring those changes to people, and I had that spirit inside of me—of revolution. But then having babies, there was an internal struggle—what has to be my first priority? That was something I had to learn as a father." He

In a city like Washington, DC, with its transient population of people coming to make money or get an education for a few years before heading to points elsewhere, it's hard, David believes, to build community. "There are places where community happens naturally, but I think in this society you have to invest in an intentional effort to make it happen and we have been doing that. We are hospitable. We always welcome friends into our home. For us, it’s very important. The village. That's something we miss from Central America." Interestingly, as if on cue, the music playing in the background shifts from

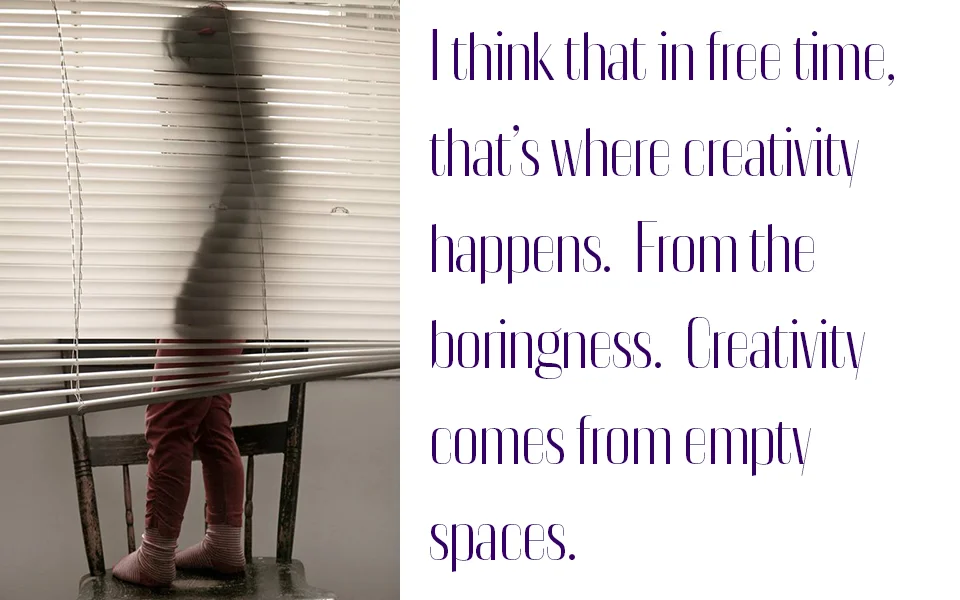

"Here, money and work interfere with what becomes a community. For some, it could mean I'll meet you in February for coffee from eight to nine at this place. For me, it's more spontaneous—spending time wasting time together—more organic. He and Lucy feel strongly that their girls be allowed to be free; not

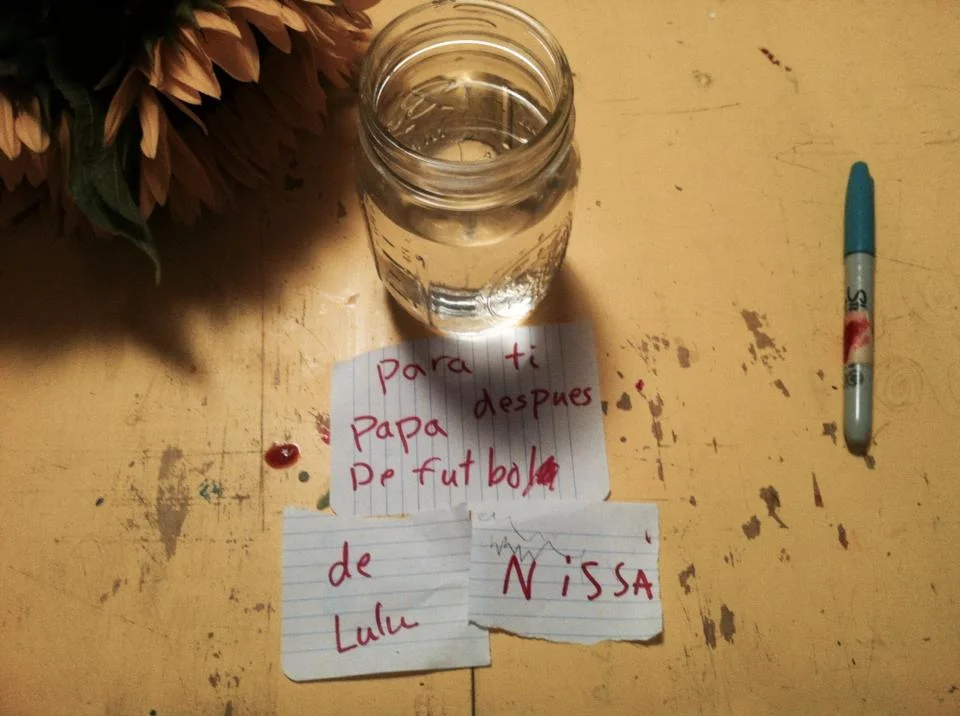

"Lulu, she’s an artist. She’s so creative. She always wants to dance, paint, make clothes. She’s also a great leader. When she’s around other kids, they make performance, she leads the performance. Everything that happens she is the center of attraction for a lot of kids, they love her. I can see her in theater, music, arts." We are making songs. (Now singing, she formerly played violin.) My hope is that we can make a little CD of her music. She sings really well."

Lulu dances. ©David Cea/

"Nissa is an engineer," he says. "She builds; she’s a mathematician. She loves math. She loves

Nissa's morning: breakfast of mathematicians. ©David Cea/

He wants the girls to know their heritage. He and Lucy speak to the girls mostly in Spanish and they teach them their history, yet "We respect their story too, I don’t want to make my story their story. We kind of let them build their own understanding of the time, of the place that they are in, but also recognizing the past somehow."

They took the girls to San Salvador for the first time last summer. "We exposed them to what's there, how people live, how people treat each other. They were in LOVE, like I don’t wanna go back!" From Nissa's perspective, San Salvador has few adults. "Because they were with kids all the time," David smiles. "No adults to say 'say no, say yes, say excuse me, say I’m sorry.' They love it! We stay at my father’s house; my sister lives next door so they wake up and run next door, ride bikes or rollerblades. Playing, playing, playing. The beach, the weather, all the people walking the street, big sound everywhere. Tropical countries are very noisy. Maybe one day we will send them or spend one or two years there. I think it will be good for them to see the world other than here. Even for me," he adds, "being here it’s like being inside a bubble and you forget about how other people live in other places. Even in my father’s house, the water is a big issue. All day, the topic is the water: how to save the water, how much water we have, who takes a bath, you need to take a bath at this time, you get one bucket of water. You are making miracles of taking a shower. Here you never think about water. There you are more aware of the sun. Is it going to rain? You need the sun to dry your clothes, so you are in touch with nature. I like that connection. When you live here, you forget; become unconscious of those things." He wants his daughters to experience doing things in accordance with nature. In the States, we have nearly unlimited access year-round to most produce; yet he believes that when limited to foods in season, people will more richly enjoy the fruity yield of a tree knowing it is offered it up for only two months.

Unbridled love and joy, the Cea way of life. Photos courtesy of David Cea.

"Living here with the kids; the life, and challenging times, and struggles, and things happening as an immigrant family, it's been important to keep a good, positive attitude, take care of our spirit, try to keep our lives happy, and feed our soul with hope and love," David says. We stay centered with peace."

David's TROVE:

The woods of Las Apalaches (the Appalachian Mountains) ©David Cea/dac photos

1. The woods. He enjoys "the peacefulness, nature, where you don’t see anything." It is a favorite spot for contemplation, meditation and prayer. "All people are welcome to the woods. I like that."

Photo courtesy David Cea.

2. Playing guitar or flute. He played guitar in a band as a teen and in the Ruta community. "When I came here, I lived in an apartment in Takoma Park [Maryland] with a woods in the back—walking distance. When I had anxiety or panic attacks, I used to run to the woods and play the flute. It calmed me really fast." That’s how he discovered that he had natural ability for the instrument. "I feel a connection with God and life when playing the flute or making music on the guitar."

Lucy at the bonfire. ©David Cea/dac photos

3. Bonfires. "I love fire— the smell, the visual, and the spirit in the fire energy. Very special."

Biker and boots.

4. Leather Boots. His favorite footwear.

5. Riding his 1977 motorcycle. He's loved Honda motorcycles since childhood, when his boot-wearing,

6. Fútbol. "I've played since I was a kid." Every Wednesday and Sunday he joins a casual group of enthusiastic "soccer" players in the District.

Photos courtesy of David Cea.

7. His collections. There are many things he enjoys collecting in multiples: ceramic mugs, knives, hats, belts and cameras.

8. His passion for Lucy.

(Top) A salvaged door and a pair of paisley pants are up-cycled as a funky credenza in David's hands. (Below) For his November 2015 exhibition at the State Theater in Culpepper,

9.

Lucy. ©David Cea/

Las niñas. ©David Cea/

Elders. (Left) Panchimalquense woman. (Right) Protestor among an alliance of pipeline fighters, ranchers, farmers, tribal communities, and their friends rallied in Washington DC in April 2014 to fight against Keystone XL.

Brian, The Sound of the Sun ©David Cea/

Chinatown, Washington, DC. ©David Cea/

10. Photography. His love for the art shows in every image, in the interplay of light and shadow he so sublimely beckons us to see. From the quiet intimacy of his portraits of Lucy to his obvious delight in observing and exquistely capturing moments of his daughters' lives to the cinematic tableaux he creates when pulling out from the macro view.

©David Cea/