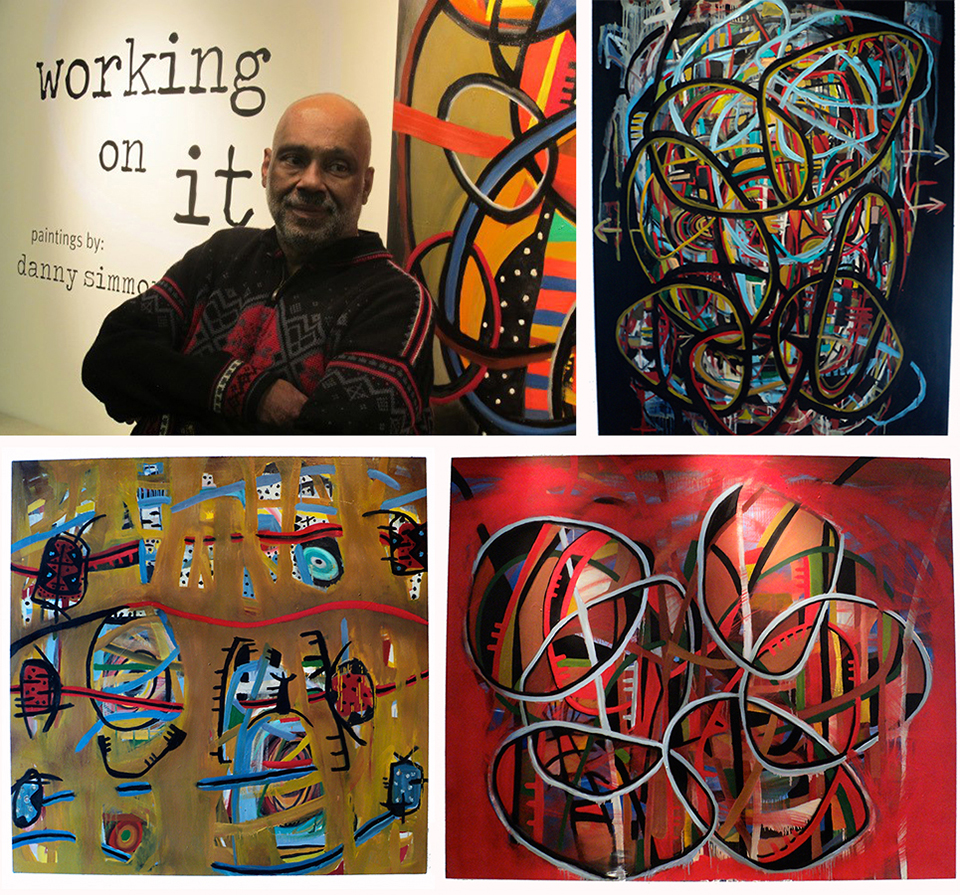

Danny Simmons photographed by Frederick V. Nielsen II.

On a recent visit to Danny Simmons’ Brooklyn home, his two greyhound rescues sleeping peacefully in the backyard, I find the inveterate collector smiling, deeply satisfied with his most recent acquisition. Not a piece for his vast collection of African and contemporary diasporic art, but a signed copy of Booker T. Washington’s Up From Slavery, to nestle amongst his many first editions (including Oliver Twist, Mickey Mouse, Naked Lunch, Howl and For Colored Girls.) Of the online purchase he says, “the only thing I go to the store to buy now is comic books.” And he’s clear about which shops he patronizes. The new crop of lofty comic sellers with their stately, dark wood interiors prompts a “too adult, that’s not the comic book experience. I want to see the toys. I want to see all the geekdom of it. For rare comic books, I go to Metropolis on Broadway, but to buy my comics I read during the week, I get them over at Galaxy in Park Slope.” It’s an obsession developed in childhood and renewed when his then 12-year-old son discovered comics.

Signed by Booker T.

“I remember pre-Marvel, I was reading DC Comics. Superman, The Flash, all that stuff. Then the Marvel age of superheroes happened, and I bought all the first of those: Fantastic Four, Spider-Man, and The Avengers. Really that’s what sparked it.” Since he didn’t save his childhood collection, he recently replaced them all. “At way high prices. Who knew?” he laughs.

Comics of the Marvel Silver Age.

Daniel and Evelyn Simmons’ first born speaks of the osmotic influences of his parents: “My father would spout poetry at the turn of anything. He was a gregarious cat. He loved his poetry and loved talking about Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen and Black History ‘cause he taught it (at Pace University.) And my mother, I’d come home and watch her sitting with her little tabletop easel in the window while she painted something. I remember the smell of it, oil paint.” Danny’s first volume of poetry, I Dreamed My People Were Calling But I Couldn’t Find My Way Home is interspersed with evocative paintings. Waxing poetic like his pops and painting like his mama, it seems natural that he’d develop a fluency for both.

Howard University alums, the Simmons’ set high academic standards for their three boys, Daniel Jr., Russell and Joseph. “But you know, I was a bad child who got caught up in the things of my day.” He recalls his late father’s battle with Alzheimer’s Disease: “one of the last things he remembered was the telephone number of Benjamin N. Cardozo High School. He had talked to the principal every day: ‘Danny did this, Danny did that.’ I did set the American flag on fire on stage during auditorium. I was suspected of blowing up the bathroom.” How true was the suspicion? I ask. He grins, full of mischief. “I do know there was a recipe for making homemade bombs and a copy of Abbie Hoffman’s Steal This Book, which I stole.” Pot, pills, protests and “plotting to do some real revolutionary shit. It was a very sixties growing up,” he muses.

With the seventies came the Rockefeller drug statutes and prison. While attending New York University, Danny, and a buddy were approached by an undercover DEA agent to score some drugs. They weren’t dealers, but it presented an opportunity to cop on someone else’s dime. “It was entrapment. We were getting the drugs for him and getting some drugs out of it. I was facing seven counts of 25 to life.” To vouch for his son, Daniel père got 50 letters from “prominent Negroes — David Dinkins, Benjamin Ward, who was Commissioner of Corrections at the time and all the Suttons.” Even the presiding judge thought Danny’s sentence draconian for a non-violent crime, so he commuted it to one to life and recommended school release. “I was in a medium security prison, confinement for sure. And violent. But it was more like camp. Rough camp, but camp. I became the guy who taught other people how to read. It was a long experience because I was away, but it wasn’t the worst thing that happened to me.” He finds tremendous value in it, “to understand exactly what — all aspects of what goes on in the world. I ended up doing 18-19 months and then another couple of months in school release.” He was able to complete his undergraduate studies in social work at NYU.

“It was emphasized quite a bit in my family to help other human beings. So I’m sure that seeped in.” His field of study, drug addiction, and subsequent recovery would imbue him with the insight and empathy to provide effective drug counseling. “I was a drug counselor for many years; I know the power of group therapy for people to open up and release stories and purge.” It was how he was able to kick. “It was all good when it was fun then I stopped paying bills and was about to lose my brownstone. One of the terrible things about drugs is you start losing things, and not just physical things but the things you care about. I ruined my marriage. You start finding excuses about why these things happened; it’s never the drugs. Finally, I said ‘I can’t do this anymore.’ I went to Russell, who’s really my best friend in the world, my little brother and said, ‘yo man, I gotta get off this.’ So he paid for a stint at Hazleden in Minnesota. I had such an amazing recovery I came back and talked to a group of people, and apparently my talk changed a number of people’s lives. How they thought about their recovery changed and they became serious about getting clean. I still have people call and say ‘thank you, Danny. Twenty years later, I’m still clean. You saved my life, my family.’ I just got a call like that two months ago.”

He culled the drug-addled 1980’s downtown art scene for the backdrop of his first published novel, Three Days as the Crow Flies. Written before his recovery, in a frenzied three weeks he produced 1200 pages chronicling three days in the life of Crow Shade. Ten years and several edits later, it was published by Atria Books. He revisited the story in ‘85, a graphic novel created with Floyd Hughes, and he plans to further meld story with visual in a big-screen adaptation. He commissioned a “great script” on the exploits of Crow & Co, but “unless somebody pops up and says ‘You know what? I read your script and here’s one million dollars,’ it will have to wait. It would take the kind of time and effort I took to make DefPoetry Jam (as co-creator and executive producer of the HBO series) to make a movie now, I just don’t have the time. I need a producer who’s gonna really run with this.”

We speak on his artistic influences from comic art to Dali (“the first artist I loved”) to Cuban artist Wifredo Lam. Discovering Lam was a revelation. “I looked at his work and said ‘that’s the real stuff, he’s who Picasso wanted to be.’ Picasso got the form right but not the spiritual aspect. All those Europeans who appropriated African art were intellectual but I felt Wifredo Lam,” he says. Lam’s influence is apparent in Danny’s early works, but he has evolved tangentially. “I had to get away from Wifredo Lam. I didn’t want to continue to abstract the human form. I remember consciously struggling to find a way to express the spiritual roots of African sculpture and art in a non-figurative way, and I found the simplest thing, the dot. It released me from figures. When dotting in a pattern it said Africa; it said roots, it said connection. The self-described, Neo-African abstract expressionist sees the “line of thought progression” from his early figurative works to dotting to the interconnected looping motifs that dominate his current work. “I don’t wanna be that guy,” he says emphatically, “painting the same painting over and over with different colors and repositioning things.” Nor does he want to fall prey to a reductive gallery system in which the arts exist solely for commerce. “The arts are for the enrichment and betterment of people and not just for commercial enterprise.”

His Gallery at Wagner opening reception, photo by Debbie Hardy; Complications and dissertations (2012); Red goes with everything (2012) and Long time coming/long time gone (2012)

Though he helms two galleries, he doesn’t consider himself a gallerist. “I never wanted to be an art dealer, but I did want to expose people to art. There’s a social work aspect. Rush and Corridor Galleries are places for people to show their work to their respective communities. We don’t push art sales. We do sell if somebody wants to buy something.” At Rush the emphasis is largely on exposure for early career artists; at Corridor, it’s exposing the residents of the community to the arts of the community. “A place,” he says, “where kids and families can come and experience art in an environment where they don’t feel pressured to be a consumer.”

He acknowledges his forbears in Brooklyn arts and his place in the community continuum. “Otto Neals is elder statesman of the arts in Brooklyn and Dorsey’s Gallery has been an outpost for artists of color for more than 40 years.” he says. He gladly honored the revered octogenarian artist’s request to take part in a group show there in February. “Dorsey’s, Spiral Gallery, Skylight Gallery at Restoration Plaza and my own gallery — all these places in the black community have been holding our artists down long before we were on the walls in Chelsea.” He recalls partying with Russell and “Soho luminaries” back when the epicenter of the mainstream art world was south of Houston Street, and the Lower East Side was its playground. But the peace and love didn’t translate for all when shows were mounted. Black artists were seldom exhibited. Danny submitted packages and slides of his work to no avail, so in the days before DefJam, he put up an exhibition of his works and those of African American sculptor Howard McCalebb at the office of Rush Productions. “We had a great show, we both sold a couple of pieces. So I went about the business of finding places and putting up shows for years.” Eventually, he eliminated the need to secure spaces by establishing a gallery on the ground floor of his Bed-Stuy brownstone. After several shows there, he moved to a Williamsburg loft “because I wanted to be more of an artist,” he adds dryly.

Sought by Annext in TriBeCa to program their gallery, Danny with the nascent Rush Arts, began to garner exposure for their artists’ works in the media. Placements on the then hugely popular tv show New York Undercover were early successes of that programming. In the second year, not wanting to return with outstretched hand to Russell (who’d provided the money the first year) Danny simply asked his brother to host a fundraiser to launch a non-profit, the Rush Philanthropic Arts Foundation. “We did it at the Puck Building and raised a quarter of a million dollars. That’s how we started Rush Philanthropic Arts in earnest and now it’s been seventeen years. Our budget is close to million dollars a year. We’re in six different high schools throughout New York City with our gallery-in-a school program, teaching the kids how to run their own art gallery.”

Holding a Master’s in Public Administration & Finance from Long Island University (on whose board he now sits) his financial approach has been to uncover ways to make things work for less money. “What was the best way to make this happen? The best way was to own the space, non-profit space that didn’t need a lot of maintenance to run. We have dedicated employees who are paid by the foundation. It doesn’t take the sales of the art to maintain the spaces. It does take a lot, a lot of work to raise the money, but it’s raised primarily through people who believe in the arts in the way that I do.”

From his private collection, works by Francks Francois Deceus and Xenobia Bailey.

“It's been a nice long journey in the arts. Along the way I’ve been writing and painting, making sure that I was not only an arts administrator of sorts but an artist as well. I’ve had my great share of shows, and I have a certain amount of recognition, but I think most of my time in the arts–about 70%– is not spent in being an artist.” He, of course, devotes considerable time to Rush Philanthropic Arts, but additionally he sits on several boards. His guiding interest is in ascertaining that these institutions are both “responsible

He realizes the power of advocating for the arts at an institutional level. “The big questions now for artists are where are we

It is this advocacy that has compelled his emergence on the BK political scene. “For many years I resisted being involved in local politics, but there are people running for elections that really care about the arts. They deserve our support. The arts are huge in our Brooklyn communities. We are a voting block, a power base if we choose to see ourselves that way. Politicians respond to constituencies. Who got me elected? Who donated money? Who are my supporters? I see politics as a viable way of getting those issues, like housing, moved forward.” He has rallied on the behalf of “artist-centric” candidates Tish James for Public Advocate, State Senator Eric Adams for Borough President and Laurie Cumbo for City Council District 35. “Laurie comes from the arts (as founder of MoCADA), and I feel very proud to be her campaign chair. She’ll certainly have other concerns than the arts, but the fact that she built her following on building a museum here in our community is a very significant thing for the arts world.”

He is optimistic about the new wave of arts champions. “There are a lot of younger people taking up the mantle of arts advocacy in a way that I think is empowering, out here doing stuff that I did: Shantrelle Lewis, Hanif (Akintola) who started Hycide Magazine.” Considering a different pace, he says, “I do envision a time when I’m just an artist. But you know after doing all this stuff, I don’t know if it would be fulfilling enough just to do that. I know I have a couple more novels that I’ve plotted in my head for years (including a “Three Days” sequel which finds Crow a decade later in group therapy: his reminiscences, relapses, and general adventures in rehab.) I know I have poetry that I’ll always write (his latest volume, Deep In Your Best Reflection, channels Eros in textable snippets) but I don’t know if standing around painting is a full-time pursuit for me.” I’d venture a guess that his incredibly generous Leo nature will need to engage and share with others more than a solitary painting life will allow. We said our goodbyes as Danny headed to Soho House to host a screening of a compilation film for Ovation TV. In partnership with Bombay Sapphire ®, Rush Philanthropic Arts Foundation conducted a nationwide search for emerging artists and featured the winners in the “Artisan Series” film. Celebrating Brooklyn creativity, Danny produced the segment, The Collage of Imagination. And his calendar remains full, celebrating art and embracing community. In just the past week or so he has hosted along with Brian Tate of Full Spectrum Experience, the Bearden 100 artist talk, and digital exhibit honoring the centenary of Romare Bearden as well taken the stage as a trustee of Long Island University for the first commencement exercises to be held at the Barclay’s Center.

In spite of his blazing schedule, he graciously sat down and shared the things he treasures most.

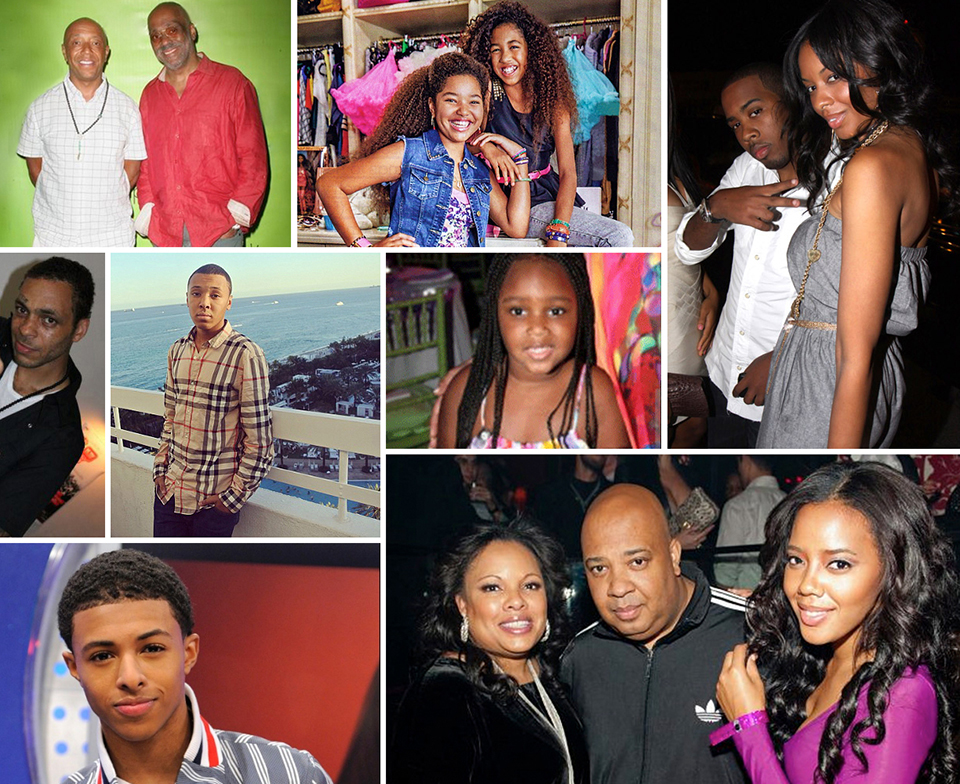

1. My family. “It’s important to me, its the core of who I am, my relationship to these people. Clockwise from left, Russell with Danny; Russell’s girls Ming and Aoki; Joey’s kids Joseph, Jr. (JoJo) and Vanessa; Joey (Rev. Run) flanked by wife Justine and daughter Angela; Joey’s son Daniel III (Diggy); Danny’s son Jamel; Joey’s son Russell II (Russy) and Joey’s youngest, Miley.

2. Rush Philanthropic Arts Foundation. “That’s my life’s work, I suppose. RPAF has affected thousands of kids and hundreds of artists. I think at last count we had 900 artists at Rush and Corridor Galleries together.”

3. My living room. A pendulous contemporary piece by Simone Leigh hangs above the sofa and is surrounded by the bulk of his African Art collection. “Most of the strongest pieces are here. Though they are all over the house, the sheer concentration of art in this room makes it so spiritually and so visually charged.”

4. Brooklyn Academy of Music. “BAM is the most powerful board that I’ve been on. BAM introduced me to all the players in Brooklyn who make decisions. Boards are mostly made up of financial people who look at institutions in a very financial way. I’m bringing an artist’s perspective. I’m always a constant advocate for community and artists.

5. All Negro Comics. His comic book dealer hipped him to the rare single-issue, 1947 comic book several years ago. Although he was unable to buy the first one he was offered, two years later when the dealer came across a copy, Danny anted upwards of eight thousand dollars for it and purchased a box frame from fellow collector Nicolas Cage.

6.

7. My art collection. “It feeds me information for my art practice. It feeds me warmth of spirit and connectedness. I think it’s important for artists to build collections, plus I can’t sit around looking at my own shit all the time.” He’s exchanged work with Barron Claiborne, Deana Lawson, his cousin Derrick Adams and many more. “Maybe half of my contemporary collection is

8. My neighborhood. “This is a community, a real neighborhood. It’s what Clinton HIll used to be until it was changed by gentrification. These people have a sense of the neighborhood and each other, they smile and say ‘Hey, how you feeling today?’ It means a lot to me. I go to the West Indian guy down the block for most of my

9. Batman collection. Atop the lintels of his bedroom are several dynamic statues depicting Batman and the villains of the Rogues Gallery.

10. My Studio. “It’s my spiritual home. It’s right next to my tenant upstairs and she’s a jazz singer so often I’m painting and she’s singing, practicing.

Find Danny's work on Artsy