Emmy award-winning producer Crystal Whaley holds one of her two gilded, winged women. Photographed by Helen Williams Nurse.

In the late 1960's, Lamar Whaley returned to his St. Louis hometown after military service in Vietnam. His neighbor, Joan Mercer, had just been sent back home after her freshman year of college in La Jolla, California where her father lived. The beautiful Joan had been pursued by too many boys, and Pops wasn't having it. Lamar had been crushing on Joan since childhood, so here was a chance to step to her. And step he did; their grand wedding made the local newspaper, the St. Louis Sentinel. Afterward, they promptly drove to Los Angeles and into married life. They conceived on their honeymoon. On February 8, their baby girl, Crystal arrived; a week later, Joan turned 21. She would mother for twenty years before passing into the next realm, emboldening her daughter for life without her.

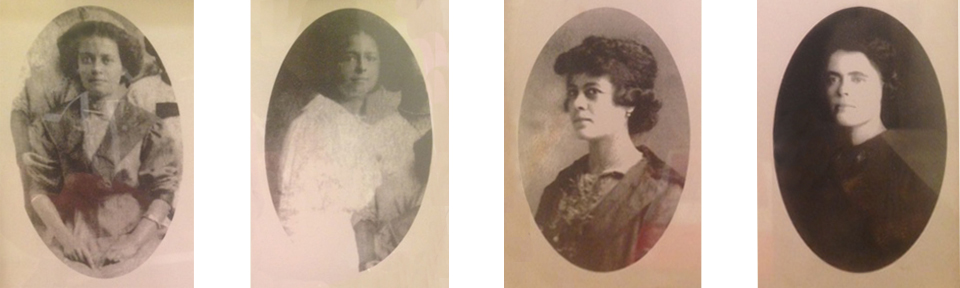

The debonair Air Force bombadier and the Catholic girls' school beauty. Photos courtesy of Crystal Whaley.

A cherubic forty-nine with a river-deep ancient soul, Crystal Whaley settles into the cozy comfort of an upholstered chair — a window seat — at Brooklyn's charming Gran Caffé de Martini in Prospect Heights. Over coffee, this child of the Great Migration, with roots in the South, Midwest and West Coast talked about how that foundation and the everlasting love of her "mama muse" shaped the woman who decamped for the East Coast at seventeen and has traveled the world in search of the stories of our people.

When I mention that I've always thought of her as a baby-faced sage, she says, "My godmother would say 'Crissy your face doesn’t change, but you’re a thousand years old.' I've always been told I'm an old soul. There are certain things that I just know, but how? I know that it’s ancestral." She loves trees, and the power, history, and memory they carry: California redwoods, southern magnolias, oaks dripping with Spanish moss and the spruce her Granddaddy planted when she was born.

Joan and Lamar cut the wedding cake. And baby makes three. Photos courtesy of Crystal Whaley.

She was a quiet, observant child— around adults, that is. "Outside of them, I was loud as they come!" she exclaims. "But I would listen to the grownups — they would almost forget I was there — I'd just sit at their feet and absorb. Or touch them and smell them. I like to smell folks, even my mother's feet—weird, I know—'cause they always smelled good, even when she wore boots," she says with a laugh. "There are scents that reverberate in my spirit. I remember the smell of my great grandmother’s powder; she would always wear Estée Lauder White Linen, you know, church lady. Scents that trigger," she says. Like greens cooking, or family patriarch Daddy Green's homemade sausage. "If I ever smell that scent, I look around, like who is from the South?" Another powerful scent memory is the layered fragrance oils of her former love from her twenties. "He had a distinct scent, always smelled so good," she recalls fondly. I tend to be attracted to men with something distinctive to my senses, how their voice sounds, how they smell."

Crissy at three; 80's fashionista in high school; fly and forty-something, the photographer/curator stands before her work. Photos courtesy of Crystal Whaley.

Making a distinction she says, "I was born and raised in L.A. but reared in St. Louis," where both her maternal and paternal grandparents migrated from Tennessee to raise their families. Crystal would spend most holidays and summers with both sets of grands and a rowdy band of girl cousins, save for one boy. Toward the end of summer a few cousins "were shipped down to [relatives in] Jackson [Tennessee] for almost a month with her boy cousins, "and then all the mamas would come pick us up. I would get picked up the day before school started and was a completely different kid than when I was dropped off. My mother was like 'What have y'all done with my kid?' I was an angel in L.A., just because there was no one to bail me out, but when I was with my cousins, we were doing ridiculous stuff, and I was the most daring. We were always ready to fight; you mess with one of us; you mess with all of us. We were down for ours whenever we had to be."

Black Girl Magic. Photo courtesy of Crystal Whaley.

"As an only child, I wanted to have siblings; I relished spending time with my cousins. I think that has shaped the way that I select my family of friends," she reflects. "I’ve always had circles of girls and women around me because I didn’t have sisters. I always try to nourish those types of spaces." However, the sense of isolation she felt also fostered her independence. "I was the cousin that always went away— and traveled by myself, often first class because my mother worked for TWA." [Trans World Airlines]

"I've been traveling since I was six-weeks-old. I had a passport at three and flew by myself for the first time at age five (the year her parents divorced). My mother would take me out of school, and we would travel — everywhere. I am so thankful that she had the fortitude and the forethought to do that." During her fourth grade year, Crystal spent extended time in St. Louis when her mom, with no family history of the disease, was diagnosed with breast cancer. "Back then they didn't have any medical protocol for anyone that young," Crystal says. Joan had a mastectomy and forwent the "then-scary" reconstruction option for wearing a prosthetic breast. "Now as an adult, older than she was at the time, I can’t imagine being thirty at best, one breast, drop dead gorgeous and a single mother? How did she do all that?"

One of Joan's best friends from childhood was June Murphy, a fit model for Yves Saint Laurent and runway model for Ebony Fashion Fair. "We would go back and forth to see her in New York and Paris. If my mother was going to Milan, I was going to Milan," Crystal says. She jokes that if her stunning mother had been just two inches taller, that she might never have been born. "She'd have been gone!"

"Auntie" June Murphy's surprise 1970's wedding day to New York designer, Jon Haggins, wearing a dress of his design. Photographer Bill Cunningham shooting the festivities on the far left. Photo: Jack Manning/New York Times.

All the fabulosity and style left its imprint. Crystal's bedroom wall was plastered not with Michael Jackson or Prince posters, but tears from fashion magazines. "I just knew I was going to be a Fashion Director for a magazine. I love getting dressed; I get that from my mother. She could take a tablecloth and whip it into a turban or a dress. But I also wanted to be an Ailey dancer. We couldn’t afford this dance school that all my girlfriends went to, but I danced anywhere I could. My cousins and I would choreograph shows that the grown folks had to pay a dollar to see. We were probably awful, but the old folks were drinking beer and saying “Do it, baby, do it!” she chuckles. In school, she continued to move her body through cheerleading and gymnastics.

Crystal's Immaculate Heart High School years: Cheerleading; hanging with her girls; tonsorial standard in the 'hood; gathered in her bedroom before heading to an "all-night punk soirée;" graduation at the Hollywood Bowl. Photos courtesy of Crystal Whaley.

She considers herself a Southern girl, but with cocktails, she laughs, "the L.A. comes all the way out— the slang, my tone, all that. I am an L.A. girl in that I love to drive. I love the beach and sun and experiences specific to Los Angeles. I went to parochial schools and in high school, all the black girls would go to the street races on Crenshaw [Boulevard]. That’s where all the gangbangers were. It was the 80’s." She lived in middle-class Miracle Mile, and many of her schoolmates were from privileged Baldwin Hills, View Park and Windsor Hills, but each enjoyed the brush with danger. "We were drawn to it because we wanted excitement," she says. "All the movies that you’ve seen; it's what we were doing. We would have our uniforms on — hiked up high — because we were civilians to all the boys. They’d be Bloods and Crips, with rollers in their hair and lowered trucks. They’d pick us up from school and give us money, and we wouldn’t have to do anything; like hold his hand, maybe. With us, their 'civilian' girlfriends they could be carefree and innocent. It was a status symbol for them; and rebellion for us. You'd have your 'proper' boyfriend and then your 'hood' boyfriend." But Crystal didn't date much in high school because the boys just weren't checking for her, she says. "My look wasn't in," she says dryly. "I was always in the sun, getting brown," which conflicted with L.A. beauty standards of the time. "I didn’t go to many of the dances. No prom. So my 'proper' boyfriend was my St. Louis boyfriend (whom she dated intermittently from age 14 to 22), and my 'hood' boyfriend was a Rollin 60s Crip. He wore blue rollers; they were the biggest rollers, so that meant he had long hair and status, just ridiculous. I didn't really like him, but I did like that he was so nice to me. I liked to smoke back then and he always had the best weed. It was fun and dangerous. They were banging, but they tried to keep that away from us because of the danger even though we'd be in spaces that were crazy, situations where anything could have jumped off. I’m sure our hood boyfriends are all dead and probably died one of those summers."

Thankfully the only shooting in her life was after she picked up her mom's camera in ninth grade. She applied to and was accepted on early decision to NYU-Tisch to study photography, but the school had no real campus life, and she knew she wasn't yet mature enough to handle that. Her mother encouraged her to consider HBCUs and specifically, Howard. "In our family, my generation was the first to finish college. Others started, but wars like Vietnam and other things got in the way. I don’t come from a family of educators. We are hard working people just a couple of decades off the farm, getting good government jobs (as my grandmother Audrey would say) becoming small business owners and owning our homes with maybe with 10+ relatives living in it as family members migrated from the South to the Midwest."

Ineice "M'Dear" Mercer, baby Crissy and Joan Mercer Whaley; Joan and her mama, M'Dear; College graduate Crystal and her grandmama, M'Dear. Photos courtesy of Crystal Whaley.

While touring Howard's campus, Crystal realized that finally, "my look was in! I just lost my mind, Everybody was grown at Howard, and everyone was FINE! I met so many upperclassmen because they were all trying to hit on my mother."

She arrived at Howard during one of the most dangerous eras in modern D.C. history when notorious drug kingpin Rayful Edmond, "ruled the city," she says, cornering the lion's share of the drug trade. "And he was paying folks' tuition; I knew a couple of those folks," she adds. "But we were happy-go-lucky. The city was still chocolate and so fun." She learned to negotiate and stand up for herself in college. "At seventeen, I made friends with the secretary to the president because I needed to get my classes validated - in layman terms it means I needed to be financially cleared to register and keep all my classes." Navigating Howard "builds character and creative problem-solving," she says. Crystal would have to call on these when at twenty years old, with impending midterms, she suddenly lost her adored mother, not to cancer, but to a ruptured aneurysm. "She was in love and dating this dude," she says, noting that her mother's beau remains in her life today. "He actually found her. She was the gem of our family and only forty-two. Everyone was shocked. We have longevity in the family— I had great-grandparents until I was 23, and my grandfather is now 102."

Crystal is grateful for the family that remains. Crissy and Dad, Lamar; Lamar Whaley, today; happy baby with Dad and Granddad; The grands. Photos courtesy of Crystal Whaley.

"Of course, it was a huge loss, but I don't have the perspective that folks are gone. I've always felt that my mother was around me. I have an ancestral altar, always connected. So in that way it wasn't devastating for me; other things that really shouldn’t have been were, but you have to learn your lessons hard in some places. I didn’t have my mother in my 20’s to help me with the nuances of being a woman." Her maternal grandmother, M'Dear, became her mama. However, M'Dear "never recovered" from the loss of her only daughter, Crystal says. "To her credit she allowed me to be an adult and make hard decisions. She trusted me, and that was empowering and beautiful. In later years, she developed dementia. I had her until I was 42."

A journalism major, Crystal shared her heartbreaking news with one of her professors. "She was about a thousand years old; probably worked at the first black newspaper ever. She said, 'I’m so sorry to hear about that, but your midterm is on Wednesday, Miss Whaley, I expect you to be here at nine AM.' I was like but you don’t under... She was patting my little hand. 'I’m so sorry; I have another student.' She would not give me an extension; she was ruthless."

"We had a huge memorial in LA and a funeral in St. Louis with family. Because I was so young, everyone was hovering around me, but I had to get back to school." Joan had been in the process of changing her insurance coverage and hadn't yet signed the paperwork when she passed away. "I got NOTHING," Crystal remembers. "So I knew I had to get a scholarship. When I got back, I took the exam, got an A and to this day I thank that professor. If she had not said you have to be back by Wednesday, I don’t know if I would have ever come back. At graduation, I thanked her. She met my whole family and said, “Yes, that was my way of getting her back here, she was an excellent student.”

The Howard years: With her head-turning mama; Crystal, second from right, with her AKA line sisters including bestie, Helen (in the red jacket); and a jubilant graduate in cap and gown. Photos courtesy of Crystal Whaley.

Though she had a love-hate relationship with the now embattled school, she believes choosing it was one the best decisions she's ever made. "What it gave me after all those years at predominately white parochial schools was a sense of family. Professors that really cared about you, your future and legacy." The friends she met during her first week at Howard, "we call ourselves the original crew," we've been friends for thirty years, through our careers, marriages, kids, divorces, and deaths. We gained a chosen family like only a HBCU can provide."

Crystal, third from left, and the team at Uptown Records, surround label founder, Andre Harrell. Photos courtesy of Crystal Whaley.

Upon moving to New York and reporting for her first day as an editorial assistant at W Magazine, she learned that her editor had been fired and that she should go home. "I was devastated. But my whole crew was working in the music industry, so I started working at a label. [Uptown Records] We were all babies, breaking Mary's [J. Blige] album at the time. I only stayed for 6 or 7 months. It was a lot of crazy sprinkled with a little bit of ghetto. The way you want to curse somebody out and leave a job, that whole fantasy? That's what I did. I cursed out my boss and stormed out. It was so good, and to this day, when I see him, he says 'I’ll never forget that. I couldn't believe you stood up to me like that; I was just in love with you when you left."

Serving 'tude since '74. Photos courtesy of Crystal Whaley.

Her godfather, a superintendent for New York Public Schools, hired her to teach elementary school; but to continue, she'd have to get a graduate degree in teaching. "I didn't want to do that," she says. Her then-boyfriend, Director of Photography on Spike Lee's Clockers encouraged her to try film producing since she was "bossy and organized." She was able to bypass the entry-level, dues-paying production assistant position. "I didn't have to go through the ropes. I badgered Alan Ferguson; he was working with Connie Orlando, who ran Hype's [Williams] company, Big Dog, so I shadowed her on one job." She got her first crack as a video producer "on a 112 remix with Biggie. We shot at night in Times Square and my lights didn't show up! I was thrown right into the fire on my very first producing job," she says. Eventually, she and Ferguson created Free Spirit Films, headquartered in Soho on Broadway. "Those were crazy fun times, and then I got the opportunity to go back to a label as a freelance video commissioner. We were doing hardcore hip-hop, we did a lot of Jay’s first album." She laughs and shares the story of getting her production budget for a video "in a greasy brown paper bag. Stacks of cash. You know, I’m 5’ 3”, and a hundred pounds then." It helped to have assistant director Mike Ellis around: "he was big, and he was always with me." She knew how video sets could be—propositions and all manner of shenanigans, so she set a standard for the production. "I wrapped my head, and I was like you’re not going to approach me or any of the women on this set the way you approach other people. I was in my twenties, and some of them were straight-up criminals," she says. "They were respectful. You know, it’s how you enter a space, and demand respect."

During the L.A. Reid reign at Arista Records, she landed a full-time gig as Director of Video Production. "OutKast, Usher, it was hot!" Until a label merger killed several jobs, including hers. So freelancing once again, she produced commercials and sent out resumes for permanent work. One was to Sesame Workshop for a position with Sesame Street. To a beloved brand losing its audience, the young music video producer brought fresh energy — and stars like crooner John Legend and Chris Brown to work it out with Elmo. She produced their interstitials, with relevant themes, like sharing and tolerance. As part of the producing team, she is a two-time Emmy winner for Outstanding Children's Series. "It's a double-edged sword," she says now that she is freelancing once again. "It can be a deterrent because people feel intimidated if they don't have one, or they assume that I'm 'title conscious' and grossly overqualified. Ultimately, I'm just trying to get a check that clears. It's not that deep. The awards look great on paper, but you gotta pay the bills."

She and a partner secured a two-year, first-look development deal with Lionsgate. "We saw a lot of really great projects come through, however, our producing partner ultimately passed on them," she says. She hopes to get another deal, though, as Principal of Plan C Media Group and live bicoastally.

At her mother's urging, she pledged Alpha Kappa Alpha while at Howard. She respects her AKA sorors in general and loves her "sands" in particular, especially her bestie, Helen Williams Nurse. "I’m a girl’s girl; not girly but a champion for women. Even though I have significant male influence and I love men, it’s women always," she says. And in that spirit of sisterhood, she co-created Oyá's Elements, We were young women working in male-dominated industries, music mostly but also journalism, film, and finance. We were smart-as-a-whip, superstar brilliant girls who needed and wanted to have a safe space to cultivate tools and weapons against misogyny and sexism. Though we all come from different spiritual walks, it is spiritually-based. We understand the power of ancestors and pay homage to that. We wanted to hone in on tools to combat all the 'isms' we faced daily and shine. Oyá (an orisha in the Yoruba/Santeria pantheon) is a sword carrying warrior kicking in doors ‘cause a lot of us were the first [women in their fields]. I was a baby producer doing Mobb Deep videos; it was crazy and at times treacherous." The group helped her find her diplomatic voice, "to manage and help to structure a group of ever-evolving women." Many Oyá's were involved with the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement. Crystal and another OE member co-founded New Afrikan Woman’s Caucus, "a part of MXGM which was deconstructing patriarchy in the spaces where we were."

With elder soror, Katherine 'Kitty' Solomon who was also initiated at Howard University; the founding members of Oyá's Elements; and the new millennium Oyás sistren. Photos courtesy of Crystal Whaley.

They have nurtured the bond over the years, mourned the early deaths of three members and occasionally opened up the circle. "When you’re carrying Oyá's name, it is an ebb and flow of constant transformation, so you can’t keep the circle closed or become stagnant. She will tear it down to the foundation in order to rebuild it stronger."

And on this foundation, they build, expanding the sisterhood. "When I first got my period, it was a day of pampering and self-care; my mama and her girlfriends did that for me. So with our babies and other young ladies in our community, we created a mini rite of passage program called Moon Day to get them comfortable with having their first moon cycle and learning the power of being a woman. They emerge from Moon Day feeling empowered, confident and better prepared. To see them, as our Moon Goddesses is just beautiful. We are humbled and honored to work with them during that sacred time. I just love it!"

Sororal feelings intact, they gather less than they once did. "Now we are at the sandwich age where many of us are caring for children and elders. So the needs have changed." But still, they make time. "In our busy lives as women, and black women in particular during these precarious times, there has to be space to be nourished and get loved up. Period. And not just self-care, Self-care is great, critical and necessary but so is getting loved up."

She finally realized a dream in New York: getting her onstage twirl on. "I danced professionally with two companies, Forces of Nature and Movement of the Urban Village. In my first year with Forces of Nature, we were at BAM! [Brooklyn Academy of Music] I was an apprentice, but I did get to dance. I came out of retirement at forty-one to dance with Movement of the Urban Village and danced for a year and a half.

Dancing with Movement of the Urban Village. Photo courtesy of Crystal Whaley.

Crystal has traveled extensively to "find and be among brown folk." In the islands of the Caribbean, including Cuba, which "rocked me," she says, and throughout Africa: "Ghana, Guinea Bissau, Ethiopia, Cote D'Ivoire, where they tried to steal my passport, I had to get real Black Girl L.A. on them. Like real black girl L.A. Then I did a music video in Senegal, and I had to carry all the money on my body. That was crazy and amazing." When she visited Goree Island and "the point of no return," she was "moved, but it wasn't a 'get me to my knees' moment." She felt similarly at Ghana's Elmina Castle. "Ghana was my first link to the continent in '95. Girl, I got to Accra, it was like Park Slope," she laughs. So she traveled alone by bus "from Accra to Takoradi to get off in the middle of the road, cross the street, go through some shrubs," and find the home of a Jamaican couple she'd met deep in Harlem.

Parading in Cuba. Photo courtesy of Crystal Whaley.

As part of the US delegation to an international youth conference in 1997 and 1998, she traveled with the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement to Cuba, with accommodations offered by Cuban families. My [host] family was the mirror image of my family." Though she doesn't speak Spanish, she connected immediately. "It was magic. An elder woman would always take my hand, and we would communicate. Whenever I would travel to a developing country, I would assimilate into whatever culture I was in, out of respect and honor. I’d get something made by the local tailor; get my hair done; learn a little bit of the language and/or a couple of phrases, and I’d ride the Cho-Cho, or whatever the communal transportation was. While in Cuba we went to a province called Matanzas where most Africans were placed when they got to the island. That place felt good, it felt like home. The next time I felt like that was in Ethiopia. All those churches in Lalibela? I felt that way there. In Brazil, I felt that way, mostly in Salvador. But Cuba? Rocked me."

These excursions were the beginnings of her research into the M'Dear Project, "where we see the matriarch, the mother in all these spaces as the same mother. That mother is in Brazil; she’s in the Blue Mountains of Jamaica; she’s in Cuba; she's in the market in Ghana or Nigeria, she’s also down south on the porch with a snuff-box and fan." When she turned thirty, Crystal traveled to interview her grandmother and her grandmother's "cousin-raised-as-a-sister, my Aunt Carrie Bell Mercer." She discovered, brokenheartedly, that though she captured footage, she'd lost all the sound, and both elders have since passed away. "Devastated, I put everything on the shelf. But I recently picked it up, about a year and a half ago to see how I could make it relevant now. I thought about the images of M’Dear and what Tyler Perry has done with "Madea" and what Martin Lawrence did with "Big Momma." I thought about reclaiming her— the ultimate mother, the one that gives the community nurturing and counsel." Though she thinks Martin Lawrence's Big Momma franchise is "straight buffoonery," she has mixed feelings about Tyler Perry's work because "I believe his intention is pure; he really feels it's an homage to his grandmother. It's not the type of film I get down with, but a lot of people do. Having a critical dialogue around that, especially around safe spaces for women, particularly now, that’s what I want it to be. That nurturing and healing that happens at the kitchen table: instruction on how to deal with things and navigate life. If you’re dealing with an abusive situation, you get the counsel of Big Momma to tell how to get the hell out. Or how to put some herbs in the pot to heal. It's a reclamation of that." Initially planned as a documentary, she is reshaping the project in an exhibition format to include "all genres where you see the matriarch: paintings, audio, video, photography. To have it live somewhere with the full-length documentary and accompanying curriculum is the goal. I think now is an opportune time. It’s called M’Dear: Reclaiming Our Seat at the Table." Working outside of the academy and museum system, she hopes to "get some critical observations and critique from people who are." Her trade is producing, but she's been "an artist my whole life. I need to develop my artist/director and have someone else produce for me."

"Photography is my first love, but I was intimidated by it," she says. Her work as deputy editor of MFON: Women Photographers of the African Diaspora bridged her producing, curatorial (she curated a photo exhibition by Howard alumni as well as fundraising programming exhibitions for MXGM), research and copyediting skills. Not since Jeanne Moutoussamy Ashe's (who writes the MFON epilogue) Viewfinders (published in 1986 and updated in 1993) has there been a book that centers the work of black women photographers. Brilliant New York-based photographers Laylah Amatullah Barrayn and Adama Delphine Fawundu envisioned a contemporary journal presenting women photographers from across the African diaspora, called MFON in honor of photographer (and Crystal's dear friend) Mmekutmfon ‘Mfon’ Essien who succumbed to breast cancer in 2001. "Founding co-editors Laylah and Delphine have been working on it for the past ten years. I knew that it might be difficult to get clearance from Mfon’s estate unless there was someone very close to her that was connected to the project, so, I submitted my work which is now in the book thinking that we might be able to collaborate on the entire project. I suggested the cover image." (Mfon's brave and beautiful post-mastectomy self-portrait) "I helped in sequencing the book, honing in on some of the stronger images, finding the creative director to create the format and look of MFON, and wrangling everything from essay submissions to last-minute negotiations with our international printer and our stateside customs broker." With her producer's background, she was the one to "reel in" the artists/editors to get their vision of this "non-profit, labor of love" to a fiscally viable space. "Our editorial assistant, Ayo Lewis is one of my former Moon Goddesses. She was a Godsend. It was a long process, but rewarding, of course." She boasts, "One-hundred eighteen black women photographers across the globe, the youngest 13 and the oldest 92. It was a crazy learning curve, a pleasure and honor to be a part of MFON."

As Mfon Essien's photo assistant, Crystal would sit in for subjects as Mfon adjusted her lighting. Here, one of many polaroid portraits. The inaugural publication of MFON: Women Photographers of the African Diaspora. Photos courtesy of Crystal Whaley.

Succeeding issues of MFON will feature four to six photographers including an emerging photographer. A legacy grant established in Mfon Essien's name will "help an emerging black woman photographer get a camera" or meet some other need.

"I'm blessed," Crystal says. "This was a learning curve for me, and I needed to have this education to move forward with M'Dear." As she looks at the MFON book with pride, she adds, "It's beautiful, it really is. Mfon, in the spirit of revolution, radically decided she was going to shift the lens, the power of the gaze and control it. She felt her 'most beautiful and most sexy' — her words — during this time. Hopefully every incarnation of MFON the journal, you’ll see a bit more of Mfon’s work."

Crystal is reflective as she speaks of her late friend. "I wasn’t able to be around my mother when she was suffering, and Mfon allowed me to be with her during hospice. I was able to understand transitioning from plane to plane through her," she says gratefully. "It also made me take a hard look at why people don’t have ease in their bodies. Some of it is genetics, but it is about nurturing. With my mother having gotten breast cancer out-of-the-blue when I was a kid, she could have gone then. But she needed to raise me to be who I am. When she dropped me off at Howard and subsequently passed while I was there, I was already formed into the woman she wanted me to be; I was cool. If she’d passed when I was in fourth grade, I would be a different person."

Celebratory hair: Joan and Crissy at Christmastime; Crystal channeling her "mama muse" for her birthday. Photos courtesy of Crystal Whaley.

“In my forties, I had a couple of years where I retreated a little bit and lost some space; fear got in, fear of missing out, not having gone the traditional route.” But she is embracing excavation. The current re-construction in her apartment building– “gut renovation to the studs” is an apt metaphor for her renewal. “If I’m under construction too, I’m fine with that. I’m getting back into abundance, repelling lack.” She believes in an intergenerational, mutually beneficial approach to recalibrating. "Get you a bevy of bad bitches who are young to get you tweaked up. And that’s it. I was a beast at 25! I need those girls. They remind me of who I was and who I continue to be."

Crystal's TROVE:

1. Baths. "I am a bath person. I try to take a bath every night if I can. It warms my bones. I am a water baby. Baths soothe me. I don’t remember when I started taking showers, but I am a bath girl. I played with my Barbies in the bath. If there’s a tub, I am in it! I mean bubbles and scent. I talk on the phone in the bathtub; I read in the bathtub; I look at social media in the bathtub; I sing in the bathtub. Everybody who knows me, knows I’m in the tub. If it’s cold, I’m in the tub. Baths are paramount because baths are how I heal. As a little girl, every year I had strep throat, so we did ice baths. When I was 27, I suffered a 'phantom ectopic' pregnancy, not in my tubes, but just around the area. Couldn’t find the egg, which led me to not having my period for five months. I was technically pregnant. The pregnancy hormones and chemicals were there, and to get everything back to normal I started taking herbal baths around the same time I discovered womb healer, Queen Afua. Baths are where I’ve always known to heal—water. When I am in the tub, I enjoy a lavender soap or any milled soap - ultimately soaking the day away."

2. Saks Fifth Avenue Eau de Parfum from Bond No.9 New York. With its classic bouquet of all-white flowers— gardenia, jasmine, vetiver and vanilla, "It smells good all the time and I just love it," she says. But I am also partial to rose because it reminds me of my grandmother." And in general fragrance reminds her of her mom. "My mother always had really beautiful atomizers, all the pretty things in her boudoir. She would just spritz and be walking out the door, so fabulous with light scent behind her."

3. A red lip. Since I wore a uniform every day, I did my makeup in high school, like beat my face. Now I can’t beat my face to save my life. I don’t know how. I’ll do a lip — a red lip. I like fuchsia, but I can’t stand pink. I feel crazy if I don’t have on lipstick. A blue red is better on me. Any brand, I don’t care. I’ve gravitated toward a red lip for forever. I’ll give you a red lip which pulls everything together. I’ll give you a lip and a look. The lip makes the look."

One of Crystal's early passports; exploring Cuba and her portrait of a Holy man in Lalibela, Ethiopia. Photos courtesy of Crystal Whaley.

4. My passport. The entrée to the travel she loves. "As a little girl, international travel shaped my independence, my adventurous nature, and my fearlessness. If I have a passport, I feel like I have freedom. I need space. Aquarians need it to think, to dream, and to create. I don’t always have the money to go, but somehow I always find it. Even in the years when I embraced 'Lack' too easily, I have traveled."

Technics turntables; Joyfully getting her twirl on. Photo courtesy of Crystal Whaley.

5. Music. "Living in L.A., I had a diversity of friends from all over, and I was open to all music. So I know punk, classic rock, new wave; I know all of the chords, I know all of the lyrics. Hip-hop came later, and L.A. had its own brand. I had an uncle who was a DJ in the Midwest, and he would send us disco and early house music albums as well as the 12-inch versions of our favorites. There was always music playing. If I don’t hear music everyday I don’t feel good, I have anxiety, something’s off."

6. Dance. "Dance gives me joy. Dancing, I am in my most blissful space. It gives me joy. If you watch me dance, you see it. And I'm a house head. I discovered [Katharine] Dunham in my twenties. She was from East St. Louis. If I'd known then, I would have been there every summer growing up."

Paternal ancestors. Crystal's great grandmother, Birdie Hunt (second from the right) and her sisters. Photos courtesy of Crystal Whaley.

7. Photographic Imagery. "We had family reunions every year and buses of folks would come down and they knew all the stories of the elders. I guess I got my thirst for images because of them. My great aunt had all the old pictures. I was always fascinated with the framing of them — oval mats and the beveled glass. I absorbed those stories."

Young Crissy; photo courtesy of Crystal Whaley.

8. Porches. "At some point, I will buy a home with a porch, a swing and a couple of rocking chairs for my porch. The patriarch of our family, Daddy Green was always on the porch with his cigar or his pipe sitting with someone who had a snuff pot - disgusting," she sniffs. "You would greet people and share stories on the porch; sit and watch the rain come; eat slices of watermelon and play games like Chinese checkers and jacks on the porch."

Double take: Crystal wearing a vibrant Martine's Dream caftan on Playa del Carmen, Mexico.

9. The beach. " I love it. I’m a perpetual sunchaser. I love getting brown. My mother was very fair, my father is darker toned, I’m in the middle. In LA, I was considered dark-skinned, in NY I’m considered light-skinned. I had a bit of an issue around color because my mother was so fair mostly because I didn't look like her then - not a full-blown complex but in LA when I was growing up, the beauty aesthetic was the lighter, the better. Constantly being in the sun there, I was always browner, and I loved it.Unfortunately my mother was tortured for being fair. She was very happy I was her brown baby."

Among the images she loves: A Late Night Kiss, Harlem, 1951 by George S. Zimbel and Carnevale di Rio, Brasile, 1973 by Mario De Biasi,

10. Kissing. "I’m a romantic. I don’t particularly like holding hands for too hard. I’m Aquarian, so I need space, and you need to leave me alone for a minute, but I love to kiss. I love to kiss all over."

Find Crystal Whaley on Instagram: @tabascofour and @themdearproject Twitter: @crystalawhaley